Last updated on February 10th, 2024

Nearly every day we’re surrounded by negative news about the accelerating rates of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Today, however, we not only have good news about a path to confronting those twin crises, but we also have a tangible tool to help us navigate that path towards success.

In one sense, it’s a surprisingly simple path – a path of forests.

We’ve always known that forests are a critical part of the climate solution, removing climate-changing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in their trunks, branches, and roots. When forests are destroyed, that stored carbon not only gets released back into the atmosphere, but the potential for those forests to remove carbon dioxide in future years also disappears. When we lose forests, we lose their climate-protecting powers, forever.

Until now, there was scant data to determine just how much potential for carbon sequestration was lost from deforestation, particularly on small scales at state and municipal levels. And without this data, government agencies, conservation groups, and others lacked information about the value of protecting different lands for carbon sequestration.

The good news is we now have a tool that can provide that data.

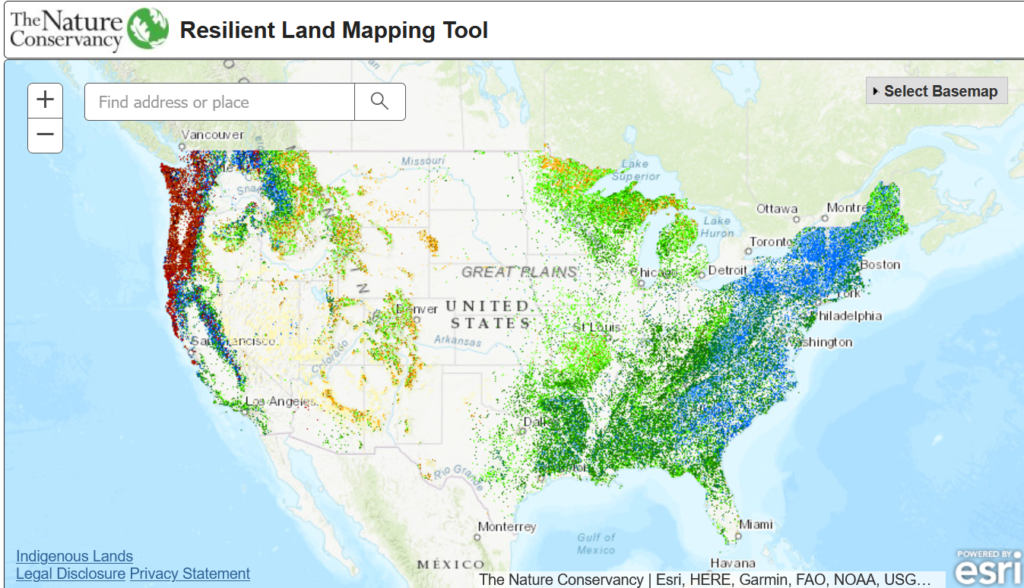

Scientists with The Nature Conservancy and Clark University in Massachusetts have worked together to create a forest carbon analysis and online mapping tool that shows the potential of forests across the continental US to capture and store climate-changing carbon emissions for years to come, even on lands as small as one-quarter of an acre.

The carbon potential numbers identified in the analysis are meant to serve as baselines that land managers can use to determine how future actions and disturbances on forests will affect actual carbon sequestration. For example, many forests particularly in the Western US will fall short of their carbon potential because of wildfire or other disturbances. Conversely, ecological thinning and removing competing vegetation can help forests reach their full carbon storage potential.

Numerous states along the East Coast have already heralded the importance of having this data, saying it will help them prioritize landscapes for conservation, improve greenhouse gas accounting, identify opportunities for small landowners to participate in emerging carbon markets, and calculate how forest protection compares to other, sometimes more costly, means of removing and reducing carbon emissions.

Adding to this good news is the fact that the mapping tool shows that many of the forests with the highest potential to capture and store carbon into the future are also among the most important places for diverse species to find refuge from climate impacts.

These carbon “hotspots” are part of a network of lands that have been identified by The Nature Conservancy as having unique geological and topographical features – such as ravines, steep slopes, and diverse soil types – that create “microclimates” where species can find safe places to live as their habitats are altered or destroyed by climate impacts.

We can now identify forests we can’t afford to lose if we want to tackle climate change and the loss of biodiversity. This could be a game changer.

Lands along the Appalachian Mountains and the Pacific Northwest – including Washington state’s Hoh River, the Altamaha River corridor in Georgia, and the Cumberland Forests that span Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia – are among the lands that have been identified to have both high potential for carbon sequestration over the next 30 years, while also providing diverse plant and animal species refuge from floods, drought, and other threats of climate change.

To be sure, forest conservation alone will not stop climate change. The climate emergency requires myriad solutions. We need to dramatically transform the global economy to reduce emissions from all sectors, including energy, transportation, manufacturing, construction, and land use.

Science led by The Nature Conservancy has shown that natural climate solutions – such as conserving forests, improving soil health, protecting grasslands, and restoring coastal wetlands – are an important part of the solution and have the potential to remove 21% of the America’s carbon pollution.

Unfortunately, nearly 1 million acres of forest lands are lost across the continental US each year due to development and other uses. That is equivalent to losing more than 100 acres of forests each hour and, with them, decades of stored carbon as well as their future ability to store more.

This new mapping tool can provide the data we need to stop this trend and allow us to clearly quantify how we can confront two of the greatest threats facing the world today – climate change and biodiversity loss—by taking one seemingly simple yet powerful step: keep our forests as forests.

Dr. Mark Anderson is the Director of The Nature Conservancy’s Center for Resilient Conservation Science.