Last updated on February 2nd, 2024

This article was originally published by the Bipartisan Policy Center. Read the original article here.

Last year marked one of the worst wildfire seasons in United States history. More than 10 million acres burned across the country, forcing hundreds of thousands of Americans from their homes and costing the nation $16.5 billion in damages. Climate change contributed to a historically dry period for the Southwest U.S. in recent decades, making devastating wildfire seasons longer and more frequent. Since 2000, wildfires have burned an average of 7 million acres per year, more than double the average annual acres burned in the 1990s. Images of burnt orange skies spanning the Western U.S. are increasingly commonplace, and the costs of catastrophic yearly wildfires are becoming unbearable. While the impact of wildfires is mostly visible—burnt forests and communities, unhealthy air, and mass evacuations—they also have a less obvious effect: carbon dioxide emissions.1

Wildfires and the emissions they release are a natural part of the disturbance regimes of many western forests, aiding in the regeneration of tree species, which in turn sequester more carbon. However, the complex cycle of ecosystem restoration from wildfires is thrown out of balance with catastrophic fire events. Severe burns impact tree survival rates and impede future growth by negatively affecting the soil. The 2020 California wildfires were some of the most catastrophic wildfire events in America’s recent history, releasing 112 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, or the equivalent emissions of 24.2 million cars on the road for a year. While the emissions released by wildfires is a drop in the bucket compared the 6,558 million metric tons of carbon dioxide released nationally in 2019, catastrophic wildfire events contribute to a feedback loop where drier conditions created by climate change further prolong wildfire seasons, increasing the prevalence of wildfires, and therefore increasing carbon emissions. Proper wildfire management is critical to reduce risks for American communities and protect fragile ecosystems.

Fire requires fuel to burn, and in the case of wildfires, trees, leaves, and vegetation are the fuel. Accumulated vegetation cause fires to burn faster, at higher temperatures, and with greater intensity, increasing the risk to communities, structures, and valuable infrastructure. Federal land management agencies along with state and local partners use fuel reduction projects to prevent wildfires from becoming more devastating by thinning vegetation and using prescribed burns. Prescribed burns are considered by many to be “good fires” since they are intentional, low-intensity fires that burn vegetation, reducing the amount of fuel available and mitigating the possibility of a larger, disastrous wildfire event. However, these wildfire management techniques are not being deployed on a wide enough scale. In fiscal year 2018, five federal land management agencies identified more than 100 million acres under their management at high risk from wildfires, yet they only treated approximately 3 million acres, leaving a sizable gap between the deployment of wildfire mitigation techniques and the high-risk acres in need of treatment.

Current Wildfire Management Approaches

Wildfires frequently cross jurisdictional boundaries, requiring strong collaboration among federal and nonfederal stakeholders on both wildfire prevention and wildfire management. At the federal level, five agencies are responsible for wildland fire management: the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service. The federal government devotes significant funding to preventing and managing wildfires. In 2020, $952 million was appropriated for DOI’s Wildland Fire Management Budget and $2.35 billion was appropriated for USFS wildland fire management. An additional $445 million was appropriated for hazardous fuels management through the USFS. Notably, while the budgets for wildfire suppression have risen over the past decade, the budgets for hazardous fuels management have remained relatively constant.

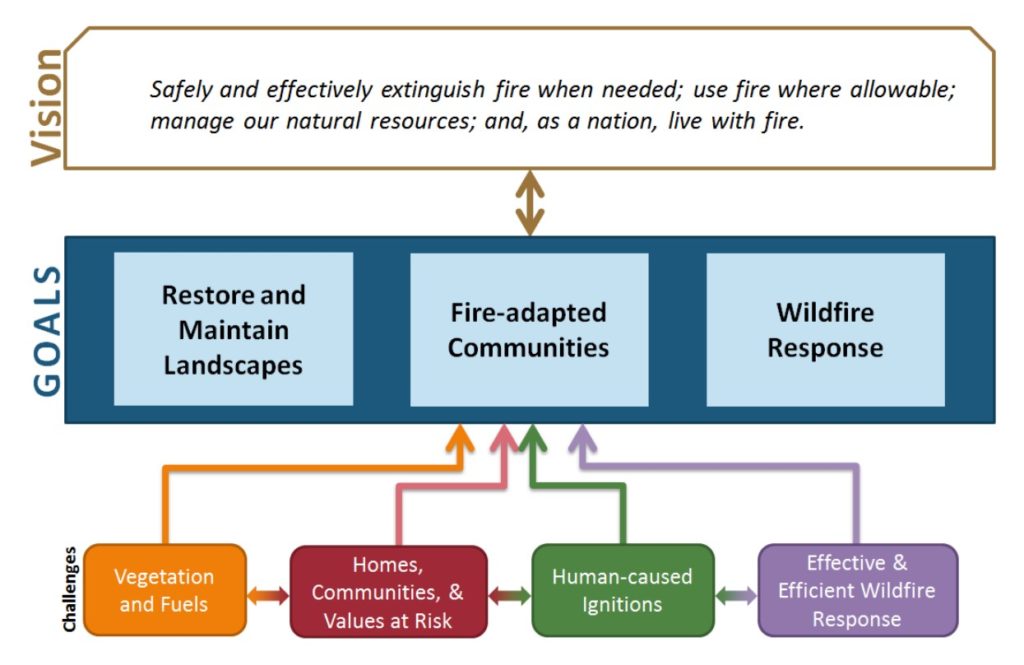

The National Wildfire Coordinating Group was established in 1976 to provide “national leadership to enable interoperable wildland fire operations” and currently has 11 members representing federal, state, local, and tribal interests. More recently, the Federal Land Assistance, Management and Enforcement Act of 2009 authorized the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy, which was completed by the agencies and their partners in 2014. The Strategy acts as a framework to guide federal and nonfederal collaboration to develop resilient landscapes, create fire-adapted communities, and improve fire response.

The Strategy divides the U.S. into three regions: the Northeast, Southeast, and West. The frequency, size, and risk of wildfires varies geographically leading to regional differences in wildfire management approaches. Perhaps counterintuitive, the West experiences fewer wildfires than the Eastern U.S. But fires in the West burn significantly more acres and are more likely to make national headlines due to the scale of damage they cause. In 2020, only 700,000 acres burned in the East, while almost 9.5 million acres burned in the West. Frequently igniting on vast swaths of public land, Western wildfires often jump from public land to private land. Unique challenges to fire management in the West include changing climate conditions such as drought, invasive species, and steep terrain. Historically, wildfire management focused on suppressing all wildfires and did not consider the important role wildfires play in western ecosystems. After 100 years of fire suppression and changes to forest management, there is a dangerous buildup of surface fuels on western lands. A landscape-level approach that includes cross-jurisdictional collaboration on wildfire management is needed to mitigate and respond to wildfires in this region.

In Alaska, fire plays a critical role in improving ecosystem productivity, removing accumulated organic matter, and maintaining the permafrost table. However, climate change is leading to an increasing number of zombie fires – fires that come back after they appear to be extinguished – across the state. These fires can continue burning due to a thick layer of organic matter common in northern ecosystems. Fire suppression responsibility in Alaska falls to three protecting agencies: USFS, BLM, and the Alaska Department of Natural Resources. Each protecting agency responds to fires within their assigned geographical area as defined in the Alaska Interagency Wildland Fire Management Plan regardless of jurisdictional agency.

Congressional Action

Signed into law in November 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) includes $6.5 billion in new funding for urgently needed wildfire risk reduction efforts underway within USDA and DOI. Of the $6.5 billion, $514 million is provided to the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service and $178 million to DOI to scale up their hazardous fuel reduction and management projects, resulting in more acres at high risk from wildfires being treated with wildfire mitigation techniques. To accomplish this, critical investments have been made in both real-time monitoring equipment to accelerate fire detection and reporting and an increase in wildland firefighters, with funding for at least 1,000 people to join the workforce, efforts to convert seasonal employees to full-time equivalents, and new compensation to recruit and retain wildland firefighters. This funding could more than double the pace of current treatments per year, but it still falls short of meeting the mounting climate threat.

Additionally, by including the bipartisan REPLANT Act and $225 million in new funding for burned area rehabilitation, the IIJA places significant emphasis on reforestation and ecosystem restoration, both of which are vital for a robust wildfire management strategy. Following wildfires, forest restoration efforts are needed to prevent further degradation of the landscape, such as soil erosion and landslides. Restoration has many benefits, including reducing wildfire risk, improved ecological and watershed health, increased carbon sequestration, and rural economic benefits from the use of forest restoration by-products. Passage of the REPLANT Act will reduce the backlog of 1.3 million acres of forests requiring reforestation by removing a $30 million cap placed on the Reforestation Trust Fund. Removing this cap will result in an average of $123 million going to reforestation each year, with priority given to forests degraded by wildfires and other natural disasters. This new demand for reforestation will support the nursery infrastructure and workforce across all land ownership types and advance tree planning as a natural climate solution. For more details on the IIJA’s significant impact on wildfire and carbon management, check out the BPC’s blog, The IIJA is a Big Deal for Carbon Management.

The IIJA’s wildfire mitigation funding is critical, but there’s potential for even greater Congressional action. During the 117th Congress, 143 bills have been introduced that would expand America’s wildfire mitigation and reforestation capabilities, 13 of which have bipartisan support. This is an enormous increase in bills introduced that address wildfires compared to a decade ago when the 112th Congress introduced 32 such bills. As wildfires grow more prevalent and devastating, the increased Congressional attention is vital to ensuring communities and ecosystems are protected. However, new strategies for combating catastrophic fire events and managing reforestation are needed to mitigate wildfires further.

The Future of Wildfire Management

Although progress is being made to improve federal and non-federal collaboration in wildfire management, current approaches are likely not enough to combat increasingly severe wildfire seasons due to climate change. According to a Government Accountability Office report, surveyed stakeholders stated the Cohesive Strategy encouraged collaboration, although there is room for improvement. New tools, resources, and innovative partnerships on the horizon offer opportunities for greater mitigation.

The All Lands Risk Explorer informs the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy through the use of geographic information system (GIS) maps that show where large fires are likely to occur and the associated impacts and benefits they would likely have. One feature of this web portal is the identification of community firesheds – areas where large fires are likely to start and spread, threatening nearby communities. This identification can support the development of fire-adapted communities by highlighting where the risk will most likely come from and who is responsible. Using this type of tool opens the door to more targeted treatments that can have a greater impact as well as better prioritization of funding. This is especially critical since a small percentage of wildfires account for the majority of the risk to communities and infrastructure.

The Nature Conservancy and the Aspen Institute have also recognized the need for change with the launch of their new partnership to improve wildfire resilience across the U.S. They are hosting a series of convenings with diverse stakeholders to develop recommendations for a comprehensive approach to boosting wildfire resilience. This work builds on previous work by TNC, which found that an additional $5 to $6 billion per year may be needed over the next decade to reduce wildfire risks and prepare communities.

The time is ripe for a paradigm shift in wildland fire management as the influx of federal funding from the IIJA is deployed. Prioritization will be essential for targeting high-risk community firesheds, and collaborative partnerships will be key to implementing new funding effectively. In addition to protecting lives, homes, and wildlife, wildfire management can contribute to climate mitigation. BPC’s Farm and Forest Carbon Solutions Task Force is focused on policy opportunities to scale natural climate solutions, including those related to enhanced wildfire resilience. In a recent statement, the Task Force called on Congress to prioritize landscape-scale climate resilience to wildfires in the current policy discourse, and will release recommendations and policy priorities in early 2022.

End Notes:

1 The specific type of emissions wildfires produce is determined by what they burn and how complete the combustion process is, so determining their net effect on the climate can be complicated. See https://climate.nasa.gov/ask-nasa-climate/3066/the-climate-connections-of-a-record-fire-year-in-the-us-west/ for more details.