Last updated on January 25th, 2024

When you mention biological soil crusts (also known as biocrusts) to Dr. Sasha Reed, her eyes light up and a smile widens across her face. For the last 15 years, this U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) biogeochemist has been on the ground and in the lab studying these soil communities that, while small, have big potential to sustain ecosystems as our planet warms. Now, thanks to increasing focus on dryland restoration and climate change science, there are new opportunities to scale up nature-based solutions with federal funding from programs like America the Beautiful.

If you close your eyes and picture a desert landscape, you might see sparse trees or shrubs and then lots of open areas of sand among the plants. While these areas look barren, they are actually filled with life in the form of soil surface communities called biocrusts. Biocrusts are the desert’s skin—a community of lichens, mosses and cyanobacteria that live on the soil surface in places where soils are exposed to the sun. Although the organisms are small, biocrusts are estimated to cover 12 percent of Earth’s land surface and can be found on all seven continents.

These complex communities play an astonishingly important role in sustaining desert ecosystems and in protecting human health. However, until recently, they have been sorely underappreciated. A growing climate crisis for Earth’s drylands and exciting research revelations are intersecting to shine a new light on the importance of biocrusts.

Dr. Reed – along with The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Northern Arizona University and Rim to Rim Restoration – leads one of the world’s largest-scale cultivations of whole biocrust communities. With funding from a Wildlife Conservation Society grant, through their Climate Adaptation Fund, and with support from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the team is working toward a scientific breakthrough that will benefit dryland communities around the globe.

Homebase for the project is the Canyonlands Research Center (CRC) headquartered at TNC’s Dugout Ranch near Canyonlands National Park in southeast Utah. The CRC is a collaboration of academic institutions, land managers, and state and federal research agencies working together on climate science and sustainable land management solutions. With powerful partnerships, the cutting-edge CRC research facility attracts some of the world’s leading scientists in climate change, biological soil crusts, rangeland management, dryland vegetation ecology and soil erosion.

Thirty-four percent of people on Earth live in dryland regions. These areas support 44 percent of the world’s cultivated systems and 50 percent of the world’s livestock. Yet drylands are home to the poorest and most marginalized people in the world. Experts estimate that 25 to 35 percent of Earth’s drylands are already degraded, with over 250 million people directly affected and about one billion people in over 100 countries at risk. With climate change impacts intensifying rapidly, restoration solutions for key dryland components—like biocrusts—can’t come soon enough.

“These organisms pack so much punch!” exclaims Dr. Reed with two pumping fists. Just as coral reefs are critical to marine habitats, biocrusts are the ecosystem engineer of Earth’s drylands. Biocrusts provide important services to people and nature by:

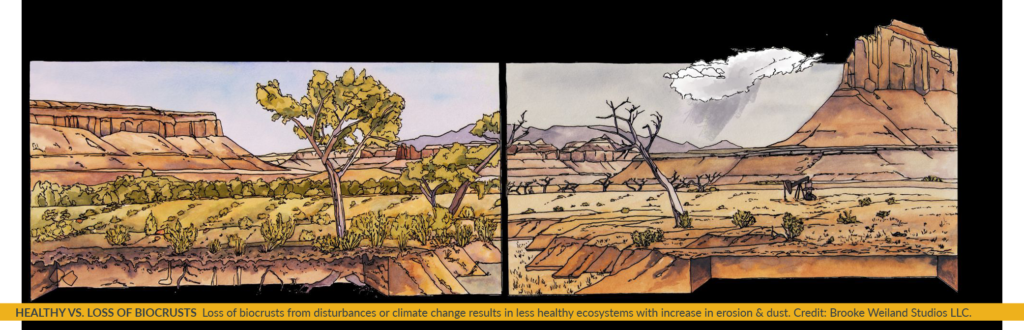

- Stabilizing Soils – Biocrusts act as a “glue” to stabilize desert soil and prevent it from blowing away. In this way, biocrusts are nature’s safeguard against dust storms that threaten human health and wildlife.

- Boosting Fertility – Biocrusts take in nitrogen and concentrates other nutrients, playing a valuable role in the diversity and productiveness of desert soils that sustain plants, wildlife and agriculture.

- Retaining Moisture – Biocrusts increase the ability of soils to retain water from precipitation, a critical process for the entire desert ecosystem.

- Storing carbon – Like all photosynthetic organisms, biocrusts take in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, sequestering carbon in soils.

Sue Bellagamba, TNC’s Canyonlands Regional Director, who is partnering with Dr. Reed, sums it up this way: “Biocrusts are the keystone element of the landscape in the western United States. If we lose our biocrusts, we could see major impacts on soil stability, vegetation and wildlife. Restoring biocrusts is a nature-based solution for mitigating the impacts of climate change and creating resilient drylands in the face of a warmer and dryer world.”

When healthy biocrusts are doing their job, they prevent the soil loss caused by wind and rainstorms. Massive dust storms, which are increasing in frequency across the southwest United States and in other drylands around the globe, are becoming more hazardous for people. Dust from one region can travel thousands of miles. These storms can limit visibility, threatening the safety of people on our highways and wreaking havoc on the human respiratory system. The reality is that if we lose biocrusts, people could also be impacted.

A bonus benefit is carbon storage. “There’s a lot of interest in carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change and we know biocrusts can take carbon out of the atmosphere via photosynthesis. However, we need to better quantify this carbon control. Our understanding of how much carbon restored biocrusts could sequester and how climate change will affect this uptake remains exceedingly poor,” says Dr. Reed.

Emerging evidence suggests drylands play a dominant role in key aspects of Earth’s carbon cycle, helping to regulate our planet’s terrestrial carbon sink. Dr. Reed and her team are working to quantify this role and to add this quantitative understanding in the context of climate change.

For years, scientists have known biocrusts were vulnerable to long-lasting damage from tires, boots and hooves. Now, a new threat looms: climate change. As heat and drought intensify for Earth’s dryland regions, the impacts on biocrusts are raising red flags. A recent study conducted by the USGS in Utah revealed that long-term experimental climate warming resulted in the dramatic loss of biocrust mosses, as well as slowed recovery of biocrusts following disturbance. Scientists warn that in the face of a warming climate, these biocrust losses could occur around the globe.

In short: Scientists like Dr. Reed and her team have a small window of time to figure out how to protect the very fabric of dryland ecosystems.

As scientists seek ways to restore damaged biocrusts in the face of climate change, they have had both advances and setbacks. Initially encouraged to discover they could grow biocrusts in a nursery, scientists were disappointed when the nursery-grown biocrusts died after being relocated to restoration sites in the desert. What they decided was that the nursery may have made life too easy for the biocrusts.

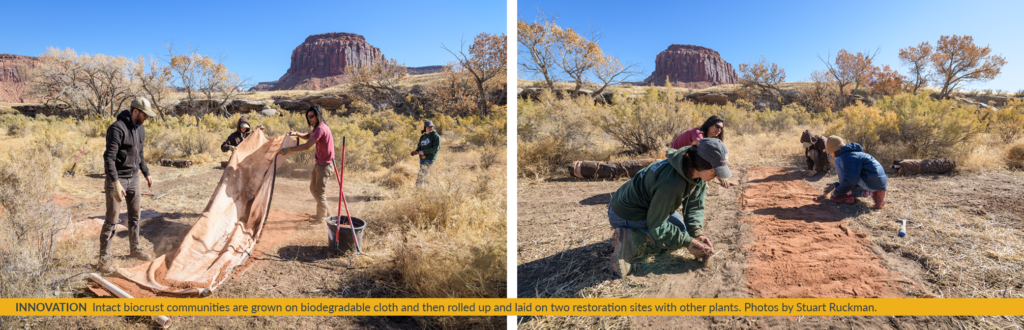

“They withered and blew away shortly after we sprinkled them on restoration sites in drought-stricken areas, such as the western U.S.,” says Dr. Reed, with a sigh. “We asked a lot of questions and came up with an idea to grow the crusts outside so they could acclimate with the harsh climate where they face relentless sun, heat and very little water.”

Researchers grew intact crust communities on biodegradable cloth on the first biocrust farm near Moab. After 8 months, volunteers unrolled the crusts on two restoration sites. The team is now monitoring these sites to determine how well the biocrusts grow. So far, they are seeing phenomenal response and future potential to advance our ability to sustain biocrusts in the face of climate change.

This forward-thinking restoration technique holds promise for scaling up the work. The size and pace of growth at the Moab biocrust farm marked an important success for restoration science.

“If the biocrust communities continue to succeed, it would be a significant advance in our ability to help resource managers bring back biocrust communities,” Dr. Reed notes. “People would be able to grow biocrusts without disturbing much land, a lot of new technology could take off, you could automate biocrust harvesting, increase the scale of the process, and open a really exciting new pathway for restoring much larger areas.”

Dr. Reed is animated…make that joyful. “I often study worrisome climate change impacts and threats, the pollution and damage,” she enthuses. “But this project, this is about hope. We are finding new ways to bring biocrusts back on the landscape, and it just feels so useful and so… good!”

More research and communication are imperative to building on the success in Utah. Restoring biocrusts across dryland ecosystems will look different in different places. While we still have many questions, biocrust climate science is happening in Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico and California, stretching all the way to Africa and Antarctica! To harness the power of biocrust knowledge and global research, a soil crust Community of Practice – called CrustNet – has been created by Dr. Reed and her collaborators. They aim to bring together biocrust researchers around to world to improve the understanding of where biocrusts are, the roles they play in diverse ecosystems and how they are responding to change. This network approach will enable learning, sharing and replicating projects.

Federal conservation programs could offer another avenue for scaling up biocrust restoration projects in the United States, providing incentives to landowners to protect and restore biocrusts, and providing support for efforts to reestablish biocrusts on degraded public lands. The America the Beautiful program offers one potential avenue of support.

In addition to scaling up biocrust restoration, increased awareness about what it is and why it’s so important is imperative. The average person has no idea what biocrusts are, which means they can’t care about it. With funds dedicated to education, partners produced a short biocrust video to educate people about these amazing and important communities.

If you want to support this effort, share a link on your organization’s social sites and with your friends and family. Though they are small, biocrusts are mighty and restoring these communities across our planet’s drylands offers a great deal of hope for Earth’s dryland ecosystems and people.

For more information, please see our Climate-Adapted Biocrust Restoration Fact Sheet. You can also access the current Biocrust Restoration Manual at: canyonlandsresearchcenter.org.

Tracey Stone is an Associate Director of Communications for The Nature Conservancy.

Dr. Sasha Reed is a Biogeochemist at the United States Geological Survey.

Sue Bellagamba is the Canyonlands Regional Director at The Nature Conservancy in Utah.