Last updated on January 25th, 2024

For most of my life, I have lived along the North Carolina coast enjoying my time spent in its coastal habitats and admiring its natural beauty. These experiences are an integral part of who I am. After I completed my undergraduate degree, my time spent appreciating the coast motivated me to begin a job as a Fisheries Technician for the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries. As my career has progressed with the division, it has been rewarding that I am helping to protect and restore these coastal resources for present and future generations.

As the Habitat Enhancement Section Chief for the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries, it’s my job to lead my team of highly skilled individuals to manage and coordinate large-scale restoration, management and enhancement programs – such as the North Carolina Coastal Habitat Protection Plan (CHPP) – for the diverse and critical habitats in our nearshore, coastal and estuarine areas that support the state’s commercial and recreational fisheries. The overarching goal of the CHPP is for long-term enhancement of coastal fisheries through habitat protection and enhancement efforts including conserving coastal ecosystems like salt marsh and seagrasses which provides many benefits to the state.

North Carolina has over 220,000 acres of salt marsh and the largest extent of seagrass coverage along the Atlantic coast, measuring approximately 105,000 acres in 2013. Seagrass is a common term used to define high salinity submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), which is habitat characterized by the presence of plants that are rooted into the ground and remain under the surface of the water during all tidal stages. The foundation of North Carolina’s coastal economy is based on the abundance of healthy habitats in its 2.9 million acres of coastal waters. Fishing, outdoor recreation, and tourism all depend on a healthy ecosystem. In addition to providing a critical home for fish, coastal habitats help reduce the impacts of severe storms, improve water quality, support birds and other wildlife, and sustain culture and a North Carolina way of life. Unfortunately, increasing stressors from a variety of land use activities, coupled with climate change, threaten the health and sustainability of the state’s coastal ecosystems. Protecting and restoring these areas so that they can continue to deliver important benefits to people and nature is key. Over the last two years, researchers and managers have been assessing another benefit provided by these coastal habitats – slowing climate change.

Coastal wetlands, including salt marsh, seagrass, and mangroves, are incredibly efficient at capturing and storing carbon in their leaves, stems, roots, and soils. Blue carbon is a common term used to define carbon captured by the world’s ocean and coastal ecosystems. Coastal wetlands can keep this blue carbon locked away for thousands of years if left undisturbed. However, when these ecosystems are degraded, stores of carbon and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) are released back into the atmosphere, which can accelerate climate change. Given their carbon storage benefits, many U.S. coastal states, including North Carolina, and countries around the world, are interested in protecting and restoring blue carbon habitats as part of their climate response strategies.

A key first step to account for the carbon captured and stored in these habitats is through the development of a GHG inventory. Accounting for coastal habitats in GHG inventories is relatively new – the U.S. EPA began incorporating coastal wetlands into the national GHG Inventory in 2017, and in 2022 started making these data available to states. But – until now – national and state inventories have lacked a key habitat – seagrass beds. North Carolina is poised to address this omission.

In 2018, Governor Cooper of North Carolina signed Executive Order 80 – North Carolina’s Commitment to Address Climate Change and Transition to a Clean Energy Economy – which includes a statewide goal to reduce the state’s GHGs to 40% below 2005 levels by 2025. The Natural and Working Lands Action Plan, published in 2020, outlines specific projects in the Natural and Working Lands (NWL) sector – including coastal habitat protection and restoration – that advance North Carolina’s climate goals by enhancing carbon sequestration, building community and ecosystem resilience, and supporting local economies.

Several subcommittees, including the Coastal Habitats Subcommittee that I chair, contributed to the recommendations of the Natural and Working Lands Action Plan and continue to support its implementation. One of the next steps spawned by the plan is the development of a GHG inventory for the state’s coastal wetlands, including emergent, scrub shrub and seagrass habitats, to help us better understand how much blue carbon is captured and stored in these areas, and what management steps we can take to enhance our blue carbon resources. As the chair of the Coastal Habitats group, I am technically in charge of the inventory development process, but I have two great champions in Paul Cough and Chris Baillie, who are leading this effort with a stellar working group comprised of federal and state agency staff, NGOs, academics, and GHG inventory experts. Once finished, North Carolina will have one of the world’s first blue carbon inventories that includes seagrasses.

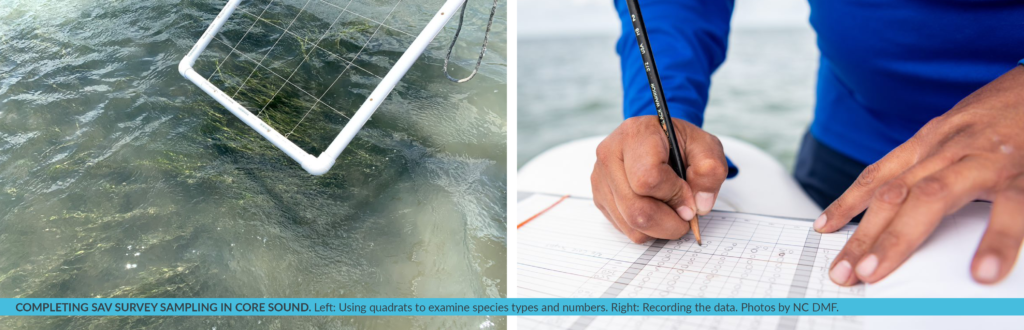

A robust blue carbon inventory relies on mapping and activity data to estimate the extent of coastal wetlands and how these habitats are changing over time. These data are then applied to corresponding “emission factors” to estimate GHG emissions and removals (i.e., sequestration) occurring in coastal areas. Although North Carolina has extensive seagrass mapping, data gaps still exist. To deal with this uncertainty, the working group utilized the expert opinion of world-renowned researchers and practitioners from along the Atlantic coast during two workshops this past spring. We also benefitted greatly from ongoing blue carbon research in our neighboring state of Virginia, whose seagrass ecosystems are very similar in species and distribution as those we have in North Carolina. Other states looking to develop blue carbon inventories can rely on expert opinion when filling in data gaps as well.

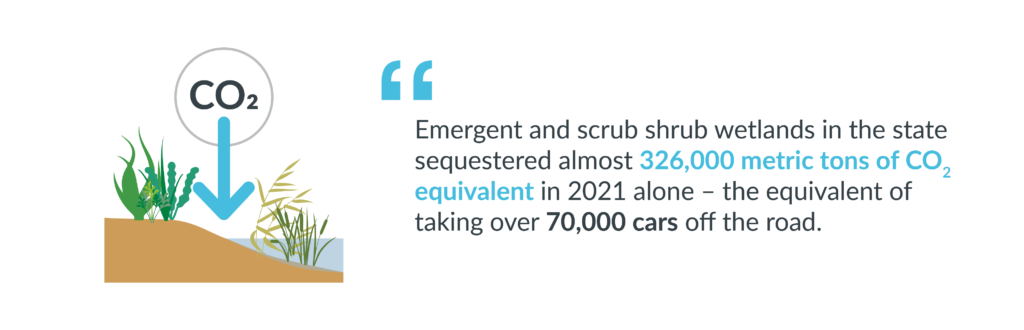

Though our work to develop the first blue carbon inventory for the period 1990-2021 will continue through early 2023, we have an initial set of findings for seagrasses that demonstrate their importance as a blue carbon habitat: in 2013 alone, seagrasses in the state sequestered approximately 66,800 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, comparable to removing more than 14,000 cars from the roads in one year. Unfortunately, the inventory also shows that seagrass habitats are on the decline, with slight decreases in GHG removals taking place over the years. In addition, emergent and scrub shrub wetlands in the state sequestered almost 326,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2021 alone – the equivalent of taking over 70,000 cars off the road. Collectively, these coastal wetlands store 48.8 million metric tons of carbon, showing how important it is to maintain the health of these habitats to keep blue carbon locked in the ground and out of the atmosphere.

The blue carbon GHG inventory will help bolster North Carolina’s efforts to protect and restore coastal habitats, including specific actions called for in the CHPP to improve the health of seagrass. When finished, the inventory will provide a tool for managers to account for the blue carbon benefits of new CHPP measures to conserve and restore seagrass habitats, such as reducing threats related to poor water quality through improved land management upstream.

We plan to release an interim update of initial findings, methodologies, and next steps for North Carolina’s Coastal Wetlands GHG Inventory by the end of 2022. In 2023, we will incorporate new seagrass mapping data, which will improve understanding of coastal wetland extent and how these habitats have changed over the inventory period (1990-2021). The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality plans to integrate the blue carbon inventory into the state’s next sector-wide GHG inventory update in January 2024. Once this happens, North Carolina will be the first state in the nation to account for seagrass in its GHG inventory, setting an example for other states to inventory their own seagrass ecosystems.

The process by which the workgroup developed the first GHG inventory for seagrass in the US can provide a model for other states to estimate the carbon value of their seagrass habitats. Throughout development of the inventory, the workgroup operated by the motto “don’t let perfect become the enemy of good.” This means that entry points exist for states to begin developing GHG inventories, even in the absence of perfect data, by incorporating expert input and learning by doing.

I have been inspired by the time and dedication of all the people involved in this effort to help North Carolina develop its first blue carbon inventory. We have had researchers up and down the coast, from Maine to Florida, share their knowledge and provide advice. We still have a lot of work to do, but I know we’ll continue to make progress to better understand and leverage the blue carbon benefits of our coastal habitats.

Jacob Boyd is the Habitat and Enhancement Section Chief, North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries