Last updated on January 25th, 2024

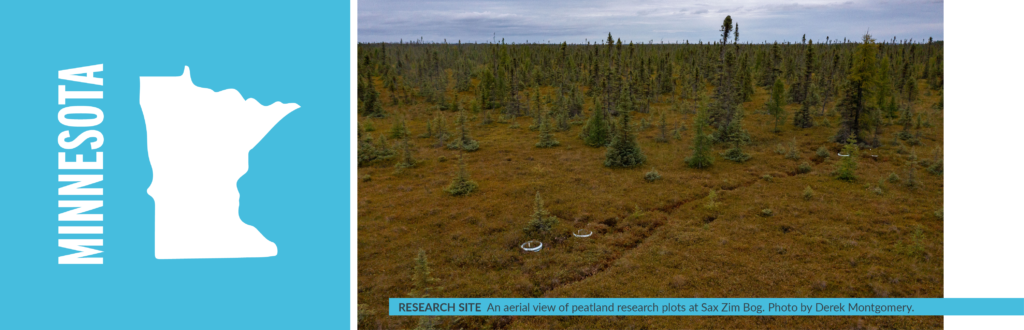

It’s a crisp fall day in northern Minnesota, and our team suits up in mud boots, jackets, and backpacks with greenhouse gas monitoring equipment. We squelch through sphagnum mosses, careful to avoid stepping on rare (and carnivorous) pitcher plants and pausing to taste wild bog cranberries. Sax-Zim bog, a watery landscape that covers more than 300 square miles of bogs, forests, lakes, and farms, is home to peatland research sites as part of a partnership between The Nature Conservancy, the U.S. Forest Service, and the University of Minnesota.

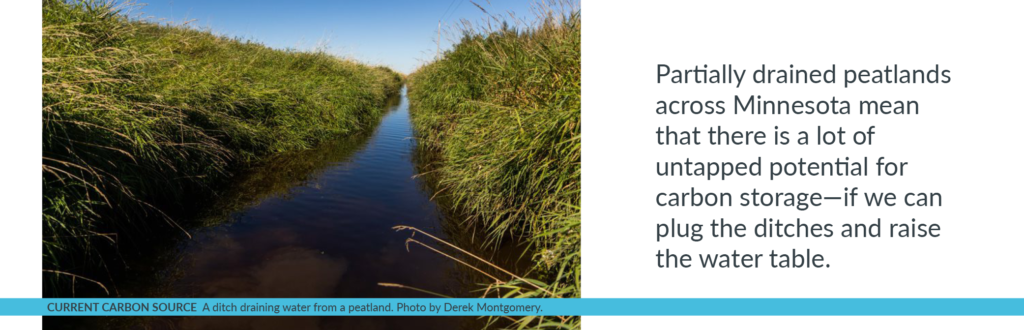

Peatlands are a unique type of wetland: waterlogged ecosystems where plant matter builds up without decaying. They cover 2 – 2.3 million hectares (almost six million acres) in Minnesota, more than any other state in the lower 48. Intact peatlands are an incredible carbon sink and store up to 30% of soil carbon worldwide but cover just 3% of the world’s surface. However, in Minnesota, 191,000 hectares have been fully drained and converted to agriculture, roads, mining and other uses. When drained, the peat is exposed to the air and releases stored carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, converting these landscapes from carbon sinks to carbon sources. Of the remaining peatlands, about 162,000 to 193,000 hectares are impacted by partial drainage from failed forestry or agricultural purposes. Ongoing carbon losses in these landscapes are estimated at a rate of about 38,000 metric tons per year– equivalent to the carbon released by burning over 154 million pounds of coal. Partially drained peatlands across Minnesota mean that there is a lot of untapped potential for carbon storage—if we can plug the ditches and raise the water table. By restoring ditched peatlands, we can likely bring back the carbon-capturing abilities of these ecosystems and help prevent major carbon emissions in the form of peat fires and rapid decomposition.

Given the critical role that protecting and restoring peatlands plays in the global carbon cycle, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in Minnesota is working with partners to develop a strategy to protect and restore peatlands as an important component of an overall climate change mitigation strategy. We are trying to answer the question: how can we best maintain carbon stores in the ground, and avoid their loss to the atmosphere as CO2?

We make our way to the first research site, a foot-wide PCV pipe dropping down vertically in the peat, where Colin Tucker of the US Forest Service will use a sensor to take carbon dioxide and methane readings. Chris Lenhart, of The Nature Conservancy and the University of Minnesota, measures peat depth—nearly two meters of partially decomposed organic matter lays below us, storing huge amounts of carbon dioxide.

Kristen Blann, freshwater ecologist and peatland science lead for The Nature Conservancy, is also onsite. She is working to develop a plan for TNC that will use field data and extensive mapping to help determine the best way to go about peatland restoration. Dr. Blann is collecting data to address some fundamental aspects of rewetting peatlands.

One big unknown is methane. Raising the water table to restore a peatland does help with capturing carbon dioxide, but it also causes a release of methane, an incredibly potent greenhouse gas. We are working to determine the levels of methane released, and are eagerly researching this question to fill in gaps in our knowledge. If the CO2 storage benefits outweigh losses of carbon to the atmosphere to methane, then large-scale peatland restoration turns out to be a winning climate solution.

As we crunch the numbers on this year’s carbon dioxide and methane measurements, we’re looking ahead to a future where Minnesota—or anywhere else with peatlands—can leverage these valuable ecosystems to help us limit the worst impacts of climate change. And restored peatland landscapes will provide more than just carbon benefits. Healthy peatlands provide public health and economic benefits for communities, such as improved flood management that safeguards property and agricultural productivity, and better drinking water quality.

Luckily, we are not in this work alone. Indigenous communities like Red Lake Nation have set an example by maintaining healthy, intact peatlands nearby by resisting pressures to drain and convert these ecosystems. Many Conservancy scientists around the world are also hard at work studying tropical peatlands. With support from the Bezos Earth Fund, TNC is able to accelerate this research and share plans, questions and findings with partners in conservation around the world working on similar research.

As it turns to afternoon, we get back in our cars and visit another peatland site, this time one where restoration is already well underway. Ecosystem Investment Partners (EIP) has worked here to plug drainage ditches, and reestablish a healthier, pre-ditching ecosystem. We conduct the same carbon dioxide and methane measurements here, which will be invaluable in our analysis of restoration opportunities.

There are still plenty of unknowns that will need to be addressed, but we are moving forward. As the research continues, it is becoming clear that restored peatlands can have a significant impact in the fight against climate change. Now we hope to gain insight into the question: Which restoration projects can get us the most carbon storage bang for our conservation buck?

The Nature Conservancy’s work in Minnesota has the potential to demonstrate a pathway for selling high-quality, scientifically-proven credits in carbon markets. This innovative financing would allow us to dramatically scale up peatland restoration, increasing the amount of carbon stored on these lands. As we build on existing science, there is a great need for state and federal agencies, private funders, and others, to prioritize this work as well.

Back in the bog, we’re wrapping up for the day. Today’s chilly temperatures mark the start of northern Minnesota’s transition to fall, when bog tamaracks will turn golden and other fall colors will burst onto the scene, before the landscape freezes over until spring. Our team, too, is transitioning toward winter, when we will be hard at work planning for the upcoming field season, finishing up a mapping analysis of Minnesota peatlands, and continuing to build partnerships. We’re gearing up to put the science to work, and to work towards re-wetting some of Minnesota’s peatlands to keep them as landscapes of climate mitigation.