Last updated on January 25th, 2024

I remember the exact moment when I began my relationship with seagrass: rooted, flowering plants growing completely underwater in a shallow lagoon off the Florida Keys. It was my 21st birthday, and I was far from my Eastern Shore of Maryland home and college, immersed in a Tropical Marine Ecology “winter-mester.” My fins and dive gear were brand new, as was my scuba certification.

I forgot everything I had learned in my scuba training as I pulsed through the most beautiful, submerged ecosystem I had ever seen. It took my breath away—literally. My dive partner had to circle back to check on me. I tried to speak to her with bubbles and gestures: “Have you seen this grass? Have you seen the fish and other animals in this grass? The sandy bottom? Have you ever experienced anything like this?”

“I mean, sure, it is beautiful,” her eyes said to me through her mask. But come on, let’s swim to the coral reef!”

That experience changed the entire trajectory not only of my professional life, but also my entire life.

In Virginia, the water in our temperate eelgrass beds is not as clear as in that tropical system. But the seahorses, the fish, the blue crabs, the amazing way the grass holds sediment and captures wave energy—it all still takes my breath away. And the fragility of these meadows. Though able to alter the water clarity with roots and rhizomes holding the sediment in place, they can be harmed by runoff from the land that brings excess nutrients and sediments, blocking light essential for survival.

The story of eelgrass along the East Coast of the U.S.—human impacts, loss and disease taking hold to strangle out this vital underwater “forest”—is one that has been repeated across the globe. Here off Virginia’s Eastern Shore, eelgrass disappeared from our coastal lagoons in the 1930s. Zero. We were down to zero acres, and all the benefits of this grass—habitat, refuge, erosion control, atmospheric carbon capture—disappeared with it. Then, in the late 1990s, scientists found a small patch of eelgrass1. They had been my colleagues back during the first seagrass experiences, when I was a graduate student at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS).

The Nature Conservancy and partners had invested in the conservation of this barrier island coastal system for decades, so maybe the protected water quality here in these shallow lagoons would support eelgrass once more?

Using a simple seed-dispersal technique, scientists and volunteers from all over the world have contributed to what is now 10,000 acres of thriving eelgrass in the Virginia Coast Reserve (VCR). This local restoration is now informing global science and recovery as well as providing further improvements to local water quality, five times more fish abundance, higher blue crab densities, return of bay scallops and capture and storage of atmospheric carbon in the soil and plant material. In twenty years, these seagrass meadows have captured 5,000 tons of carbon— equivalent to the yearly carbon dioxide emissions of 3,500 cars!

Our coastal systems are among the most studied in the world— and home to the University of Virginia’s Long Term Ecological Research program2. And here is where a methodology to quantify the amount of carbon that is being sequestered in seagrass beds was developed. Methodologies for carbon projects provide the procedures for quantifying greenhouse gases in habitats, like restored eelgrass beds. Standard-approved methodologies are used to generate carbon offsets, which can be sold on the voluntary market.

The restored eelgrass in Virginia’s coastal bays is one of the great large-scale success stories in marine restoration, and now it’s the first place on the planet soon to have a validated and verified seagrass blue carbon market project. We are now in the final stages of the approval process. We have quantified how much atmospheric carbon is being stored in these amazing grass beds and aim to have carbon offset credits issued by the end of 2022—establishing a model for similar seagrass restoration projects worldwide.

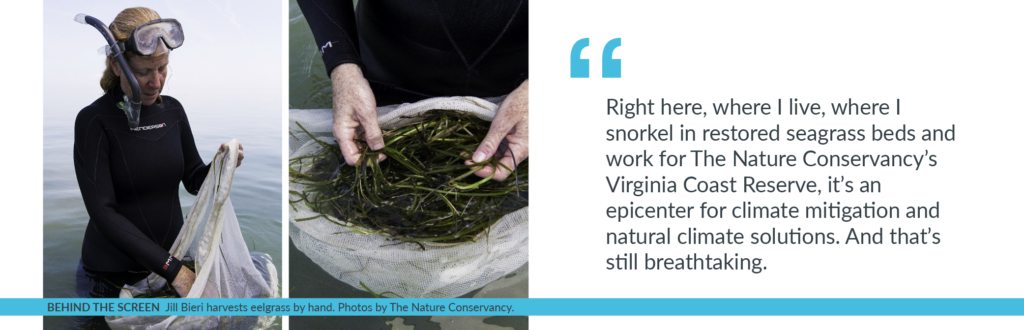

Since the Commonwealth of Virginia owns the sandy bottom on which this successful restoration has taken place, state legislation was proposed, supported, and passed in 2020 allowing carbon market participation by the Commonwealth. This legislation stipulates that revenue generated would be used for further monitoring and research in these eelgrass beds—a win-win for the state. This brings the project full-circle, as 20 years ago, initial funding for this endeavor was provided by Virginia’s Coastal Zone Management program. Right here, where I live, where I snorkel in restored seagrass beds and work for The Nature Conservancy’s Virginia Coast Reserve, it’s an epicenter for climate mitigation and natural climate solutions. And that’s still breathtaking.

Please visit the Virginia Coast Reserve website to learn more.

1 In the 1990s, scientists from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) found a small patch of eelgrass and figured out how to restore it in this system. They have spearheaded the restoration work ever since.

2 The University of Virginia’s Long Term Ecological Research program developed the methodology that is being used to quantify the amount of carbon that is being sequestered in seagrass beds.