Last updated on February 14th, 2024

Adapted from American Farmland Trusts’ Mulligan Farms Soil Health Case Study

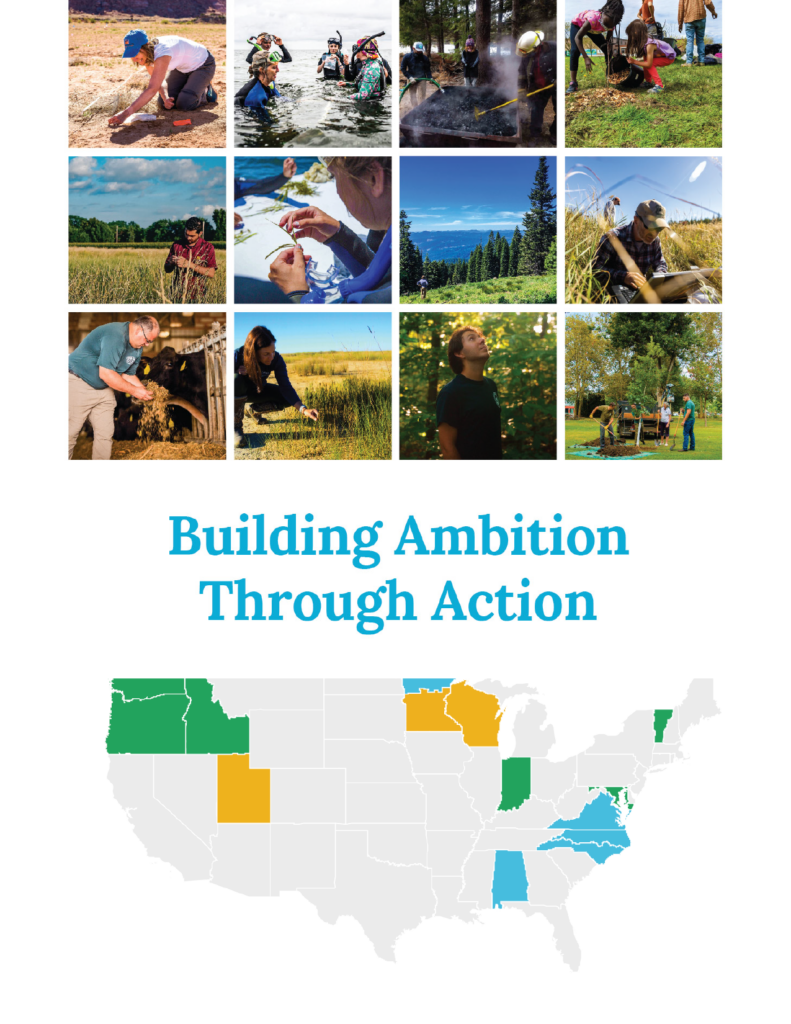

Across the US, farmers have been adopting new farming practices that provide benefits not only to the farmer, but also to the environment. There are countless names for these adaptive practices including soil health, climate-smart, conservation, and regenerative practices. Although there are a variety of terms to describe these practices, they often refer to methods that improve soil health. With improved soil health comes a multitude of benefits including enhanced resilience of land to flooding and drought, improved field operation efficiency, and environmental benefits. These environmental benefits may include increased carbon storage in the soil, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and reduced nutrient and sediment runoff into our waterways. Below we feature one farmer that participates in the Genesee River Demonstration Farm Network and has successfully adopted soil health practices, highlighting the economic and environmental benefits they have experienced.

Introduction

Forrest Watson has farmed with his aunt Lesa and uncle Jeff on their 1,500-head dairy in western New York since 2008. Currently they farm 2,618 acres and practice an eight-year crop rotation with winter wheat, alfalfa/grass, corn, and occasionally other forage crops.

The farm constantly seeks to improve efficiencies and provide the best care for their animals, lands, and employees. In this effort, Forrest learned about soil health through participation in conferences and readings. As a result, Forrest has adopted cover crops, reduced till farming, and a comprehensive nutrient management plan.

With the goals to improve soil health and productivity with fewer nutrient inputs, Forrest began experimenting with no-till and cover crops in 2015. He started experimenting with no-till on 75 acres of wheat. Since then, he now no-tills across his farm except for 150 acres of corn that he strip-tills. However, Forrest transitions strip-tilled fields to no-till as soil health improves. Both strip-till and no-till are methods of reduced-till farming, which can be defined as limiting soil-disturbing activities such as less frequent tillage, shallower, less intensive passes, and less area disturbed. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS), reduced tillage can improve soil health, reduce soil erosion, reduce energy use, and have positive impacts on air quality.

After an initial year of experimenting, Forrest went “all-in” with cover crops. This was possible, in part, due to the farm receiving financial assistance from the USDA-NRCS. When a primary cash crop is not present, cover crops can be sown in as an alternative to bare soil over the winter and early spring when precipitation is high. Cover crops have been shown to improve soil health, repress weeds, control pests, slow soil erosion, and enhance the availability of water. Cover crops also have climate benefits by increasing the total amount of photosynthesis that takes carbon from the atmosphere, which then can increase the total amount of carbon added to the soil each year. Forrest observes that the cover crops are improving the soil, enabling easier no-till drilling which in turn saves them time. “The feeling of needing to till due to compaction is virtually gone,” says Forrest. “We’re breaking up compaction with roots instead of iron.”

In 2018, Forrest began ‘planting green’, which refers to no-till planting a cash crop into actively growing cover crops. The cover crops are then terminated, usually with herbicides, to enable the growth of the cash crop. The delayed termination of the cover crop enhances its benefits.

Mulligan Farm works with consultants to implement a Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan. Since 2008, Forrest has increased the frequency and intensity of their soil testing by introducing grid sampling, begun split applications of chemical fertilizers, and switched to injecting their manure. Manure injection is a relatively new technology to apply manure with minimal soil disturbance. These improvements have optimized fertilizer application rates, timing, volume, and location while reducing odor and nutrient loss.

Soil Health, Economic, Water Quality, and Climate Benefits

American Farmland Trust (AFT) conducted a marginal analysis using the Mulligan Farm’s Cornell Dairy Farm Business Summary (DFBS) dataset from 1998–2019 to answer the question, “Can soil health practices be adopted while improving economic performance?”

This analysis looked at the benefits and costs before and after implementation of soil health practices. The study was limited to comparing crop production income and cost variables that differed between the conventional “before” period (1998–2014) and the soil health “after” period (2015–2019). Variables taken from the Cornell DFBS survey include acres, yield, production by crop, fertilizer, seeds, spray and other crop expenses, and various machinery expenses. More details on the approach of the analysis can be found here.

The DFBS data showcases that Forrest was able to adopt soil health practices while improving economic performance as the farm’s net income increased by $75 per acre per year, or $196,350 annually, for the 2,618-acre study area, achieving a 129% return on investment.

One way the farm decreased costs was reducing the cost to hire, rent, and lease machinery by $27 per acre. This decrease was driven, in part, by the switch to no-till which reduces labor time and improves efficiency. The farm also decreased fertilizer costs by $11 per acre. According to Forrest, he has reduced fertilizer applications due to better nutrient capture with cover crops and injecting instead of spreading manure. Additionally, costs related to fuel, oils and greases decreased by $19 per acre.

Can soil health practices be adopted while improving economic performance?

There were also increased costs due to adoption of soil health practices. Although machinery costs decreased in the hire, rent, and lease cost category, they experienced an increase in repair, depreciation, and interest costs by $12 per acre. The cost of seeds across all crops increased by $8 per acre. Additionally, spray, such as herbicide spray for cover crop termination, and other crop input expenses increased by $38 per acre.

Overall, Forrest has increased net income. This is due largely to the increased value of crop production by $76 per acre and to the reduction of tillage passes. Additionally, yield resiliency also improved as the data showed more consistent annual yields, but this benefit is not included in the marginal analysis as difficult to value.

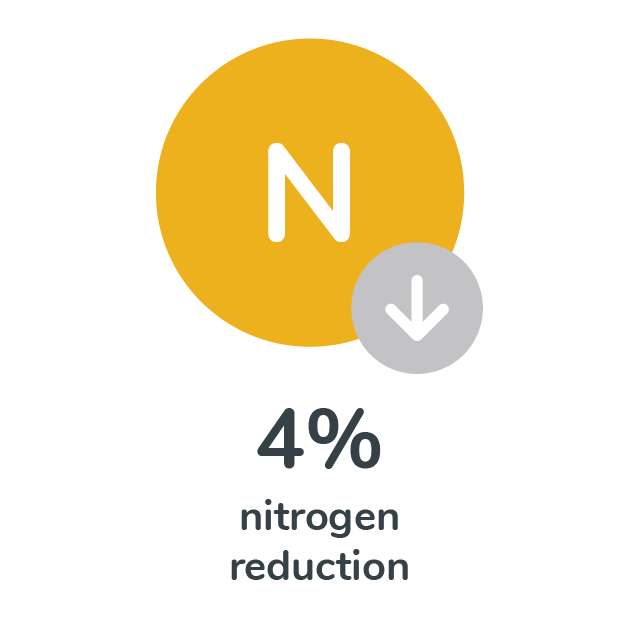

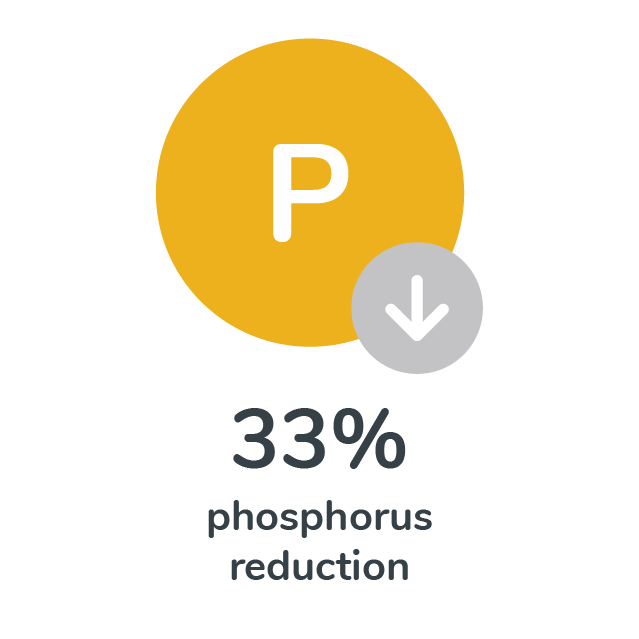

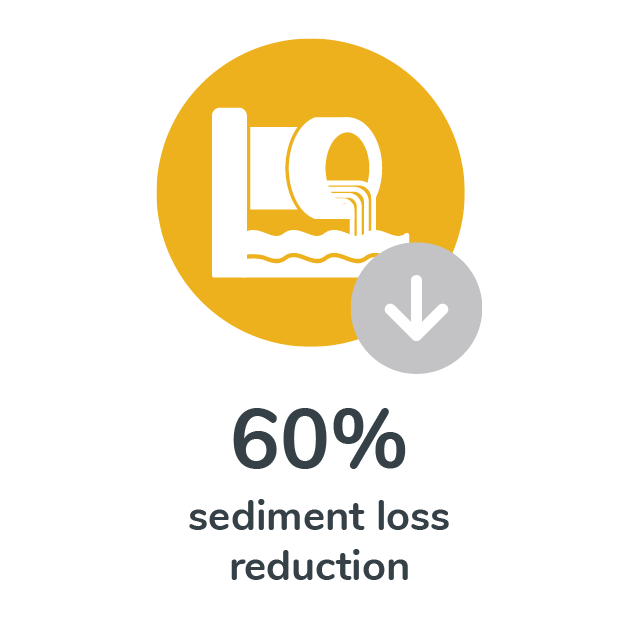

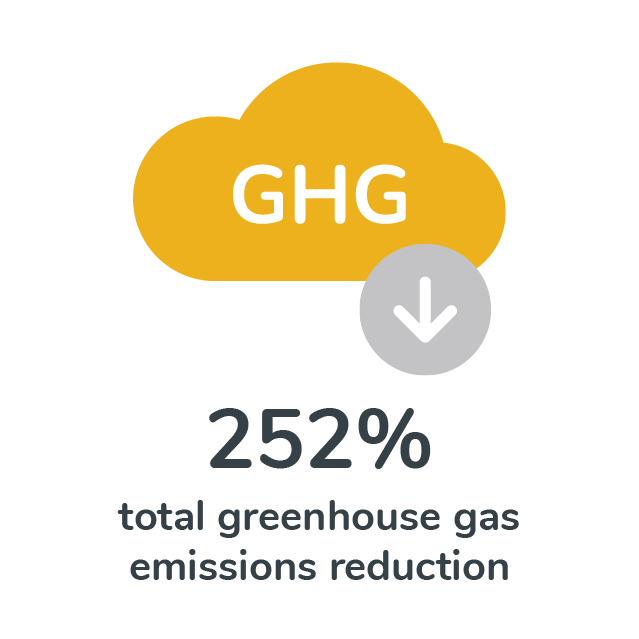

In order to estimate water quality benefits and greenhouse gas emission changes, researchers used USDA’s COMET-Farm Tool to analyze one of Forrest’s 35-acre fields as a representative field. The results estimate that the farm’s use of no-till, cover crops, and nutrient management reduced nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment losses by 4%, 33%, and 60%, respectively, and resulted in a 252% reduction in total greenhouse gas emissions, which corresponds to taking two cars off the road. With over 396 million acres of cropland across the US, emission decreases of this amount on one farm showcases the extensive potential for scaling up these benefits nationwide.

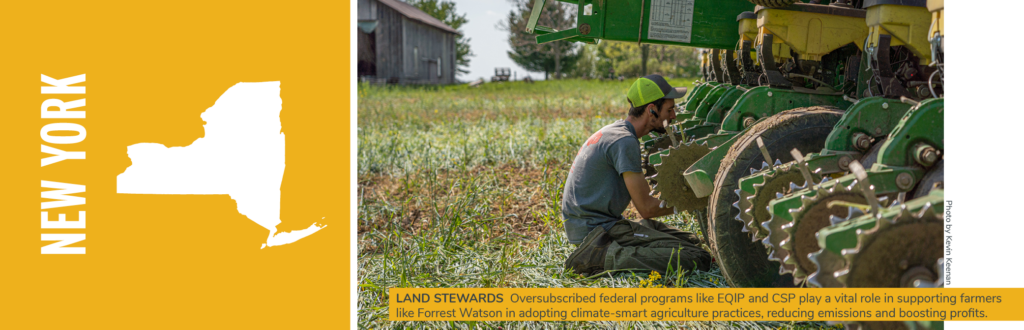

Like Forrest Watson, farmers can also adopt Soil Health Practices with financial support

To help Mulligan Farm adopt these soil health practices, the farm received assistance from two federal programs, which are supported by the federal Farm Bill. The Mulligan Farm received financial support from the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), which provides financial assistance to farmers to support them in integrating climate-smart farming practices on their lands. They also received financial support from the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) for planting cover crops. The CSP works one-on-one with farmers to enhance existing efforts and develop a conservation plan integrating new conservation practices. Note that the financial assistance the Mulligan Farm received was not factored into the economic analysis conducted by AFT, indicating the benefits of soil health practices outweigh the costs even without federal assistance.

Farm Bill agriculture programs, such as EQIP and the CSP, offer routes to scale up adoption of soil health practices nationwide. These programs can assist through not only financial assistance, but also by supporting the data collection, research, reporting, and verification that is needed to further improve understanding of the benefits of soil health management. These programs are supplemented by the recently enacted New York state law, the Soil Health and Climate Resiliency Act, which will provide additional support to the state’s farmers to adopt climate-smart practices.

Closing Thoughts

Mulligan Farm is committed to using the most environmentally friendly practices to guide crop production. “You can’t give up after the first little failure,” says Forrest. Adoption of these soil health practices supports improved operational efficiencies. For example, less labor going to tillage allows labor to go to activities that provide additional value like cover crop establishment, double cropping, and nutrient management. Forrest has observed improvements in soil health such as reduced soil compaction and more consistent and higher crop yields. Overall, Mulligan Farm has managed to improve economic performance while investing in soil health practices.

Additional Resources

Download project fact sheet

(includes pathways for scaling)