Last updated on November 18th, 2024

Blue carbon ecosystems, including seagrasses, salt marshes, tidal forests, and mangroves, are increasingly recognized as powerful nature-based solutions for mitigating climate change, also known as Natural Climate Solutions. These ecosystems can play a crucial role in sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. One study estimated that each acre of coastal wetland can sequester ten times more carbon than tropical forests. In addition, blue carbon strategies offer numerous co-benefits, such as enhanced resilience to storms and flooding, improved water quality, protection of wildlife—including commercially and recreationally valuable fish populations—economic advantages for coastal communities, and the preservation of areas important for cultural and spiritual practices. A recent survey conducted by U.S. Nature4Climate found that 92% of voters across party lines strongly support restoring coastal wetlands to reduce flood risks, provide wildlife habitat, and help address climate change. This widespread public backing highlights the growing recognition of these strategies as essential components in the fight against climate change. The combined climate mitigation potential and significant co-benefits provided by coastal blue carbon habitats are key reasons why states like Oregon, Louisiana, Maine, California, New Jersey, and North Carolina are harnessing blue carbon solutions into their climate change mitigation plans.

At the forefront of this crucial work is the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), where dedicated scientists are uncovering the mysteries of blue carbon and its significance in addressing climate change. The U.S. Nature4Climate team spoke with scientist Jaxine Wolfe from SERC to learn more about their efforts to advance blue carbon and help states utilize it to meet their greenhouse gas reduction goals while delivering multiple benefits to communities.

The Importance of Blue Carbon as a Natural Climate Solution

“Wetlands are really excellent at a lot of things. They’re culturally significant, nursery habitat for commercial species of fish and crab, a place for refuge, nesting for waterfowl, and they provide storm surge protection and help absorb runoff,” Wolfe explained, highlighting the multifaceted value of these ecosystems beyond carbon storage. It’s essential to support the communities who rely on and benefit from these ecosystems. Thousands of people live in coastal areas, making it crucial to involve them in efforts to enhance their resilience against increasingly frequent and intense storms. “The educational aspect cannot be overstated because these are people’s backyards, and these communities will be the ones most vulnerable and impacted,” Wolfe stated. Additionally, empowering these communities to take action is vital. “Once people are aware, the next question often is, ‘What can I do? I want to help but feel powerless.’ It’s essential to create more opportunities to lower the barriers to community action towards protecting and restoring wetlands,” she emphasized. “This makes the whole effort stronger because people can directly connect to it and say, ‘I did that’ or ‘I advocated for that. Now we have living shorelines in our neighborhood instead of just gray infrastructure.'”

Learn more about the Lightning Point Restoration Project

“Leveraging these ecosystems and how we find solutions using natural ecosystems to mitigate climate change impacts is really important. While they may not be the silver bullet, they’re a very important piece of the puzzle, and I think that they can do a lot for us. There are a lot of great infrastructure solutions coming online for climate mitigation, but we have natural ecosystems right here that can help us. There may be an initial investment to restore a degraded wetland, but that investment pays for itself over time. We need to have that long view.”

Jaxine Wolfe

“If we conserve, restore, or create these ecosystems and continue to treat them well, they’ll take care of themselves, and we don’t need to plug them in or charge them or mine resources to fuel them, for them to provide the ecosystem services that they do. Carbon capture is only one of these benefits, but I think maintaining that total ecosystem perspective is really, really important,” Wolfe added.

The Coastal Carbon Network: Bridging Science and Policy

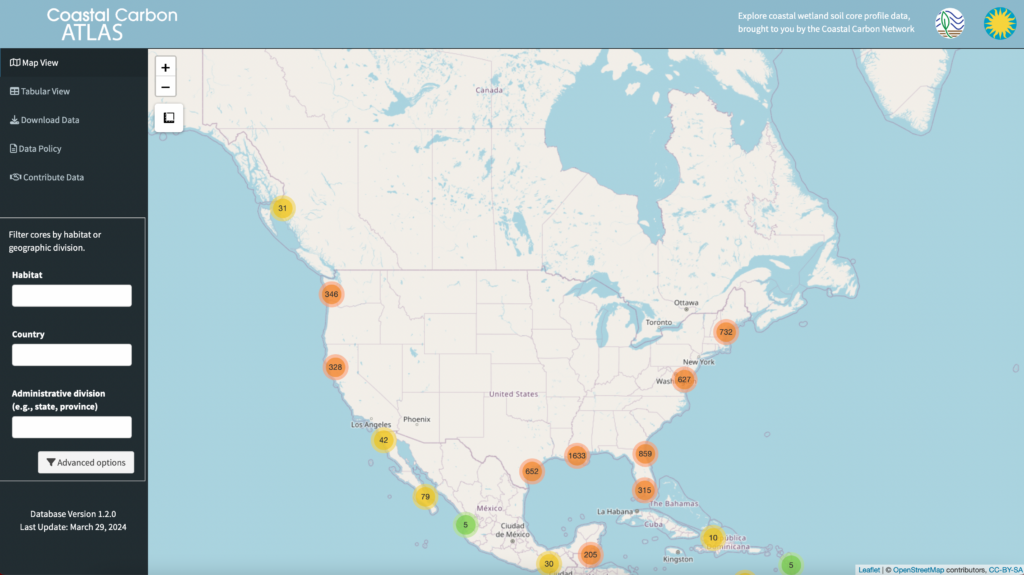

“The Coastal Carbon Network is a consortium of coastal wetland scientists and practitioners in coastal land management,” explained Jaxine Wolfe. The network aims to accelerate discoveries in coastal wetland carbon science and improve ecosystem management. Wolfe emphasized the importance of a robust data foundation to inform policy and predict how these ecosystems will respond to future climate scenarios. “We build that foundation by facilitating the sharing of open data and analysis products,” she said, highlighting the network’s commitment to community feedback and stakeholder involvement. To accomplish this, the Coastal Carbon Network developed the Coastal Carbon Atlas, an interactive web application that “democratizes access to carbon stock and sequestration data for tidal wetlands worldwide, including marshes, mangroves, and seagrass beds”. Researchers and curious minds can explore, query, and download data from these critical ecosystems.

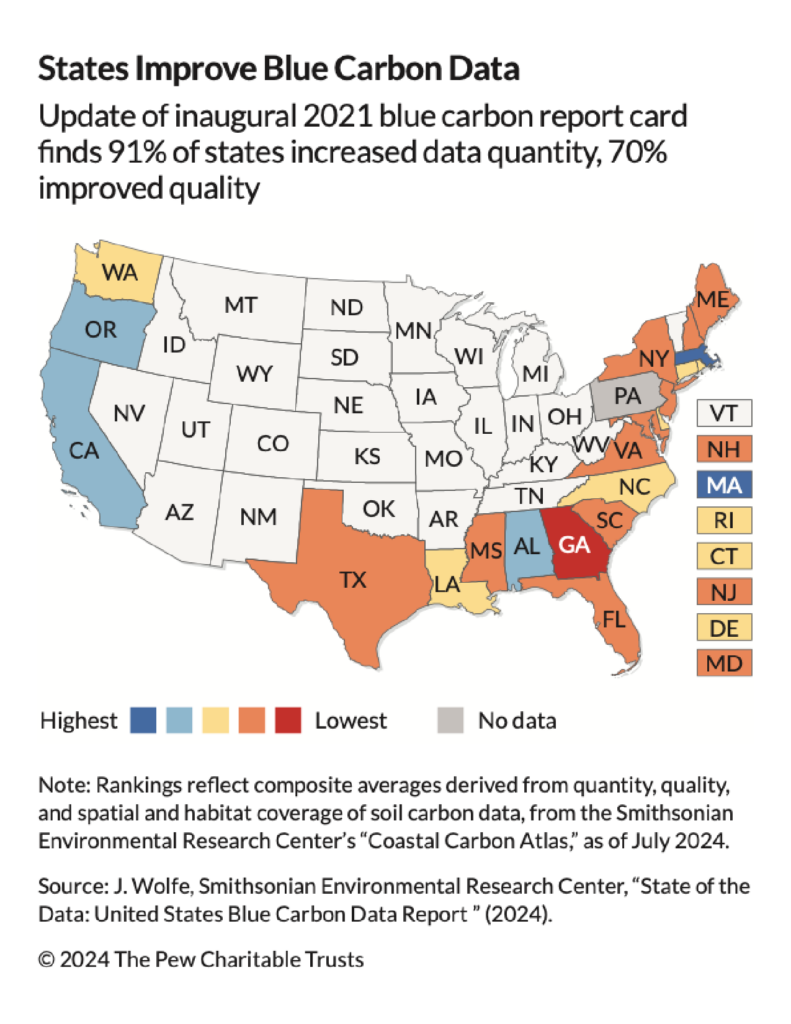

Another key initiative of the Coastal Carbon Network is the Blue Carbon Inventory Report Card. The report card assesses the quantity, quality, and coverage of data available in different states, providing a baseline for blue carbon assessments. “We provide recommendations for individual states on where data coverage is lacking,” Wolfe noted. This tool helps states understand their data needs and improve their data collection efforts to support blue carbon initiatives. Wolfe concluded, “The report card shows a state’s baseline and where improvements can be made in data coverage,” highlighting the network’s role in enhancing blue carbon data and supporting informed decision-making for coastal ecosystem management.

Resources provided by the Coastal Carbon Network:

Download the latest report on State of the Data: United States Blue Carbon Data Report

Strategies for States to Enhance Blue Carbon Assessments

Wolfe emphasized the critical need for investing in data stewardship to improve state blue carbon rankings and enhance greenhouse gas inventories. She advises states to allocate specific resources or funding for these efforts, making it a dedicated line item in their budgets. “Investing in data stewardship is crucial for building capacity to integrate coastal wetlands into greenhouse gas inventories,” she stated. Wolfe explained that data limitations often hinder progress and stressed the importance of political discussions to facilitate this investment, noting that providing context and understanding can garner necessary support.

Additionally, Wolfe highlighted the importance of preserving existing data and targeting new data collection to improve coverage. “We need to establish baselines for restoration and understand how ecosystems are changing,” Wolfe explained. Engaging stakeholders and finding common ground is also crucial for success. “Finding common ground and recognizing that data will guide us is essential,” she said. Targeted data collection should address gaps and enhance the comprehensiveness of blue carbon assessments, leading to better-informed decision-making and policy development.

Wolfe shared examples of successful utilization of Coastal Carbon Network resources by other states. “Pew, Silvestrum Climate Associates, and other Pacific Northwest researchers have used the database to develop white papers and influence policy,” Wolfe mentioned. For instance, the California Air Resources Board, working with the state’s Natural Resources Agency, leveraged findings from SERC’s data inventory efforts to encourage inclusion of coastal wetland habitats into their proposed climate change scoping plan. North Carolina’s Coastal Habitats Greenhouse Gas working group also cited the network’s work in their interim report in 2022 for the state’s first coastal habitat greenhouse gas inventory.

Wolfe highlighted the network’s collaboration with Silvestrum Climate Associates to update the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory, integrating new studies and estimates of carbon accumulation rates for vegetated coastal ecosystems. This update resulted in a significant increase in soil accumulation rates. “Between 1990 and 2022, the annual average increase in removals was 2.3 million metric tons of CO₂ equivalent,” Wolfe proudly shared, equating this to the mass of 15,000 blue whales over the entire time series. She emphasized the ongoing development of new tools, such as an inventory calculator, to provide more accessible and summarized data for stakeholders.

Overcoming Data Challenges in Coastal Carbon Science

Wolfe and the team at SERC face significant challenges in creating resources for the Coastal Carbon Atlas due to data inaccessibility and varying data-sharing cultures. “Often, the data exists but is not accessible,” Wolfe explained, noting that valuable information is frequently locked away in publications or on individual hard drives. This issue is compounded by researchers’ limited bandwidth or reluctance to share data due to personal investment. Wolfe stressed that “data sharing is built on trust,” and overcoming these challenges involves building strong relationships and ensuring researchers receive proper credit.

“The Smithsonian is known for its curation of an archive of historical artifacts and connecting this history to present day and making these resources accessible in a way that promotes learning and action. To me, data is also a historical artifact. It’s our record of these ecosystems. We are the conveners of that. We’re the librarians, in a sense. Each data set is like a book or a record, a snapshot, a moment in time. Putting all this information together allows us to have a more enriched understanding of these ecosystems. That’s why our database is referred to as the data library.”

Jaxine Wolfe

To address these issues, Wolfe and her team actively reach out to researchers to help archive and publish their data. “We were able to drum up some small funds internally to work with individual researchers at various institutions that had a lot of data that was not publicly available,” she said. Collaborating with researchers and students, they have published around 19 different datasets covering aspects such as carbon stock and accumulation rates. This effort not only makes the data accessible but also fosters a community of practice around data stewardship, emphasizing the importance of proper data curation and documentation.

Despite their efforts, the team faces challenges due to a small core group and limited resources, making their work time-consuming. Wolfe noted, “We curate data on a study-by-study basis, which is very time-consuming.” However, their dedication has resulted in documenting nearly 15,000 soil cores over seven years. They continue to seek ways to streamline the process and engage more researchers, enhancing the comprehensiveness and usability of the Coastal Carbon Atlas. Wolfe underscored the importance of promoting an open data culture to ease the sharing and integration of valuable information, ultimately aiming to make data more accessible and useful for researchers, policymakers, and community stakeholders.

Inspiration and Innovation: The Global Change Research Wetland at the Smithsonian

At the heart of the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, the Global Change Research Wetland stands as a beacon of hope and inspiration for blue carbon science. “It’s one of my favorite blue carbon spots because of the important work being done there,” Wolfe stated. This marsh in the Chesapeake Bay region has been a living laboratory since the mid-’80s, exemplifying the power of long-term research and its profound impact on understanding our changing world. The pioneering CO₂ experiment—one of the longest-running of its kind—has not only revealed the effects of elevated atmospheric CO₂ but has also sparked innovative studies on sea level rise, nitrogen loading, warming effects, and invasive species.

Wolfe finds the ongoing research “inspiring and mind-blowing,” especially its exploration of “cross-terrestrial, aquatic interface interactions” and adaptation to phenomena like ghost forests emerging due to rising sea levels. Each visit to this vibrant ecosystem deepens her appreciation, as she reflects, “Every time I visit, it’s just so inspiring.” The interplay between field observations and experimental data at this wetland continuously enriches our models and validates predictive approaches, creating a dynamic cycle of discovery and action. For Wolfe, this wetland is not merely a research site but a powerful symbol of nature’s resilience and the relentless quest for knowledge, driving the pursuit of blue carbon science with every new question it inspires.

Harnessing Blue Carbon: A Pathway to Climate Resilience and Community Well-being

Blue carbon ecosystems play a vital role in sequestering carbon and offer a range of co-benefits to coastal communities. From storm surge protection to supporting fisheries and providing wildlife habitat, these ecosystems enhance the resilience of coastal regions. By engaging local communities, raising awareness about the value of blue carbon ecosystems, and involving stakeholders in restoration and conservation efforts, states can harness the full potential of these natural resources for climate change mitigation (Natural Climate Solutions) and community well-being. As we look towards the future, developing new tools and resources, such as an inventory calculator for coastal carbon, will further support state-level efforts to monitor and manage blue carbon ecosystems. By expanding our knowledge, engaging diverse stakeholders, and advocating for the protection and restoration of blue carbon habitats, we can make meaningful strides in addressing climate change and building a more sustainable future for future generations. The work of dedicated researchers like Jaxine Wolfe and organizations such as the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center is paving the way for a brighter, more resilient future driven by the incredible potential of blue carbon ecosystems.

Special thanks to the Pew Charitable Trusts for collaborating with U.S. Nature4Climate on this article.

Scientist Highlight: Jaxine Wolfe

Combining Passion and Skill: Jaxine Wolfe’s Work at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center

“I’ve been at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center for over four years now. I started in February of 2020, right before the pandemic,” said Jaxine Wolfe, a data scientist whose journey began with an undergraduate degree in biology from Northeastern University. “During this time, I took classes and pursued internship opportunities that were formative in crafting my foundational understanding of the ecosystems I work with now, and also in developing the data skills I use today.” Wolfe’s early experiences with coding in biostatistics and internships at institutions like Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary shaped her expertise in data analysis, leading her to a role at SERC where she applies her skills in marine ecology and data science.

Wolfe emphasized the importance of understanding the context in which data is collected. “I believe in a well-rounded understanding… As someone working with this information downstream, it’s crucial. It gives you a better understanding of the field challenges and why data might raise questions,” Wolfe said. Wolfe’s work at SERC involves standardizing and analyzing data from various studies, ensuring they are comparable and reliable. Wolfe’s hands-on experience in the field, including international training programs and blue carbon projects, has deepened her appreciation for the data she works with, underscoring the value of fieldwork in informing data-driven research and policy.