Coastal wetlands support a huge range of life on Earth and provide the major benefit of capturing and storing carbon—so-called “blue carbon.” Conserving and restoring these ecosystems can contribute to broader efforts that combat climate change.

Because states in the U.S. largely set the policies governing their coastlines, they have opportunities to prominently incorporate blue carbon into their climate policies and goals. And because officials increasingly realize the role quality data plays in determining how much blue carbon is contained in their coastal habitats, including salt marshes, forested tidal wetlands, mangroves, and seagrass beds, The Pew Charitable Trusts recently hosted a webinar that brought together experts from two organizations focused on collecting blue carbon data and making it readily available.

The discussion with representatives of the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) and the Pacific Northwest Blue Carbon Working Group (PNW Blue Carbon Working Group) detailed information and tools that can help states better understand their blue carbon resources and how officials can enhance and improve their states’ data.

Recognizing the role that blue carbon can play in advancing climate goals, Pew began working on the issue in 2018, engaging with agencies, researchers, and stakeholders in multiple countries and states. Jennifer Browning, director of Pew’s Conserving Marine Life in the U.S. project, told the webinar’s attendees, “As states continue to integrate blue carbon into state climate strategies over the coming year, we see an opportunity to help states come together to address common issues and challenges around developing blue carbon inventories, setting goals, and developing management strategies.”

Browning specifically noted work underway in three states: Oregon, which is the first state to incorporate blue carbon in a proposed carbon sequestration and storage goal; California, which also is enacting policies to incorporate blue carbon into management of its natural and working lands; and North Carolina, which is accounting for the carbon sequestration and storage ability of its seagrass habitats, the first state to do so.

Browning also announced that this webinar is part of a forum Pew is building for states interested in incorporating coastal blue carbon into their climate mitigation goals and plans. The network plans to share information, create and disseminate scientifically sound materials, and provide experts and state policy officials with opportunities to discuss the latest in blue carbon science and application in the state policy arena.

Research led to states’ “blue carbon report card”

A major focus of the webinar was Pew-funded research conducted by SERC, which curates the Coastal Carbon Atlas, a central digital compilation of global blue carbon data.

“States are really the engine for a lot of the blue carbon science policy that’s developing in the United States, and trying to support state level actions is an important goal,” Pat Megonigal, SERC’s associate director for research, said during the webinar.

Jim Holmquist and Jaxine Wolfe of SERC developed four metrics to assess data in the Coastal Carbon Atlas for coastal states:

- Data quantity (the number of “cores”—or soil samples—relative to coastal wetlands area in the state).

- Data quality (how valuable the cores are in assessing blue carbon).

- Spatial representation (how well dispersed sampling efforts are across the state’s coastal wetlands).

- Habitat representation (how well habitats sampled match their estimated area in the state).

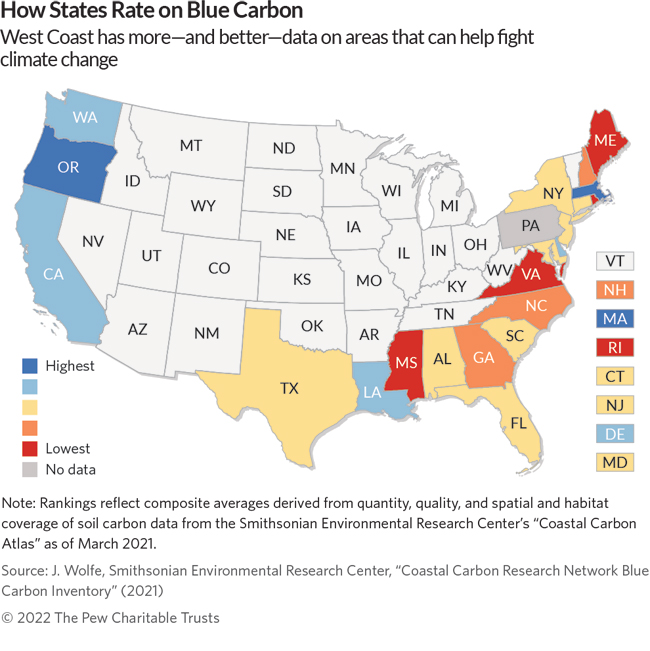

SERC then developed a “blue carbon report card” that provides a composite score for each state across all four metrics, summarized in the map below. For rankings by individual categories, see the State-Level Blue Carbon Data Report Card in the Coastal Carbon Research Coordination Network Blue Carbon Inventory report.

The highest-scoring states were Massachusetts, Oregon, Louisiana, and Washington, Wolfe, SERC’s research technician, told webinar attendees, with Delaware and California also rating highly. All of those states generally shared three traits: local investment in sufficient, high-quality data; research projects launched in the past five years in response to emerging blue carbon science; and researchers who actively collaborate with the Coastal Carbon Research Coordination Network, a SERC-sponsored consortium of biochemists, ecologists, social scientists, and managers working to expand coastal carbon science.

The research determined that at least five states had room for improvement in their data collection and/or representation: Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia.

“Collaboration between researchers and networks to increase data access is really important,” Wolfe said. This includes collaboration to synthesize existing data, publishing new data to increase access to data, and ensuring data is accessible and well documented, she added.

Lack of data may drive low ratings

The reasons states didn’t fare well on the report card could largely be because relevant data isn’t yet publicly available, Wolfe said. “Don’t be discouraged if your state is not performing the way you’d expect. These findings provide a baseline to enable targeted sampling efforts, and measure future progress.” Blue carbon scientists hope the inventory encourages public data sharing, which will improve results for all states, she added.

Also presenting on the webinar was Chris Janousek, an assistant professor at Oregon State University and a member of the PNW Blue Carbon Working Group, which helped provide data for the SERC analysis. Established in 2014, the group’s work now spans from northern California to British Columbia.

In a recent study of blue carbon stocks in the Pacific Northwest, the working group found that seagrass meadows held the smallest amount of carbon stocks, marshes offered intermediate levels, and forested tidal wetlands—including conifers such as the Sitka spruce and other trees that tolerate brackish conditions—stored considerable amounts of carbon. Oregon’s forested tidal wetlands—which support fisheries, improve water quality, and protect communities from flooding—store more carbon per acre than almost any ecosystem on Earth, but have declined 95% from historic levels.

“The high carbon stocks they hold provides additional motivation for thinking about their restoration and conservation,” Janousek said. The group has now created a database with data from Mexico to Alaska to help researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders.

States should share their data

Both SERC and the PNW Blue Carbon Working Group stressed that they can help states understand blue carbon and how conserving and restoring coastal habitats can advance climate goals. They encouraged researchers to contribute to the expanding understanding of blue carbon by sharing their data for integration into SERC’s Coastal Carbon Atlas.

“We work with a lot of people’s data,” said Holmquist, a SERC research associate. “So, if you’re shy about your data being messy or poorly formatted, don’t be shy in front of us.” In addition, SERC is working to develop interactive tools to help users better interpret the atlas’ data.

To learn more, state officials and researchers can contact SERC and the PNW Blue Carbon Working Group.

Pew strongly supports this work because better understanding of coastal habitats’ blue carbon contributions will bolster science-based policies and management, which in turn can advance climate mitigation, adaptation, and biodiversity.

Alex Clayton is a principal associate and Sylvia Troost is a senior manager at the Pew Charitable Trusts. They work on incorporating blue carbon into climate action plans for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Conserving Marine Life in the United States project.

This article was originally published by the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Conserving Marine Life in the United States Project. Read the original article here.

U.S. Nature4Climate recently convened an expert panel to discuss the challenges and opportunities surrounding blue carbon as a climate mitigation strategy, including strategies to protect and restore coastal wetlands. Read a synopsis of that conversation in our Decision-Makers Guide to Natural Climate Solutions Science.