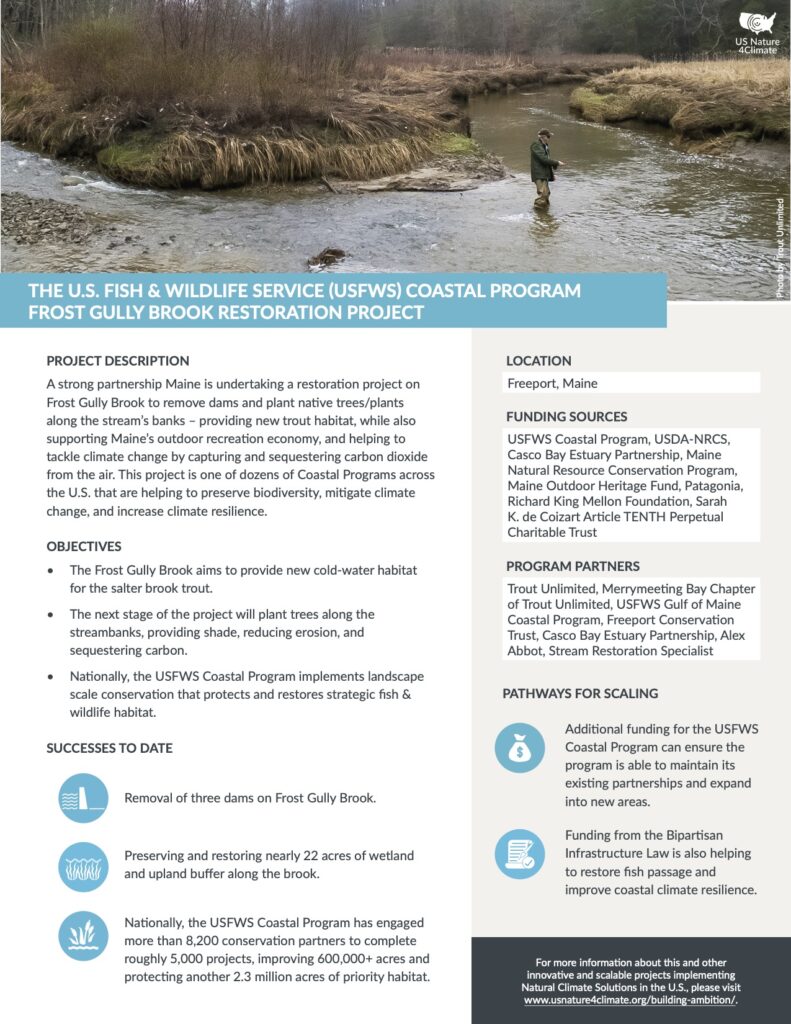

The benefits of urban trees are well documented. According to the USDA Forest Service, “urban forests help to filter air and water, control storm water, conserve energy, and provide animal habitat and shade.” They also provide tangible financial benefits to communities, with one study finding that urban trees can reduce energy use in residential areas by an average of 7.2%, saving billions of dollars.

Urban trees also provide benefits for climate. Indeed, research from American Forests and The Nature Conservancy reveals that planting 522 million to 1.2 billion trees in urban areas could mitigate between 8.7 million and 25.8 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions per year respectively – equivalent to removing between 1.94 million and 5.74 million cars from the road. To realize these benefits, it isn’t enough to just plant trees – it is also necessary to maintain the trees after they are planted to ensure that they survive and thrive. Failure to plan for trees’ long-term survival can lead to the rapid death of newly planted trees. It’s also incredibly important to maintain large, long-lived mature trees currently providing optimal benefits while new trees grow large enough to do the same.

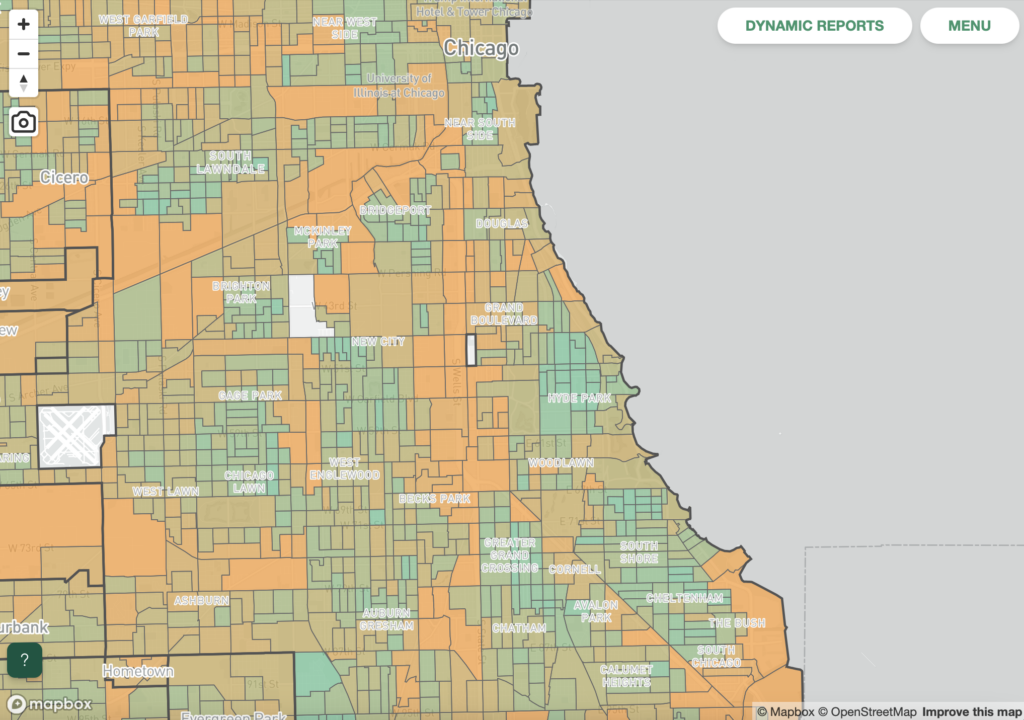

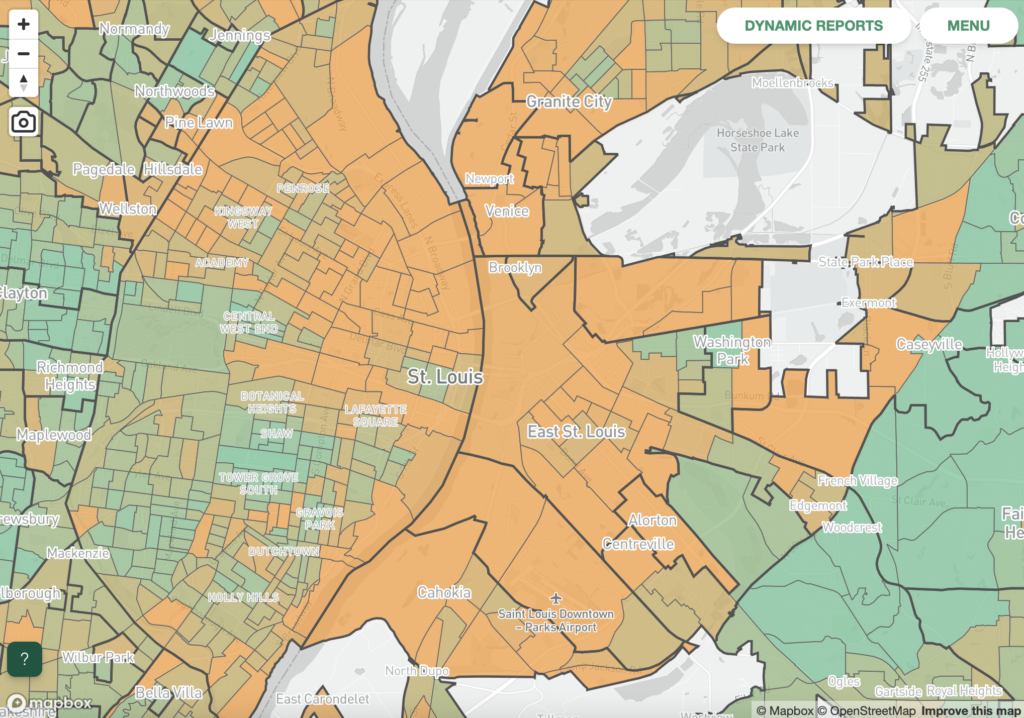

Unfortunately, the benefits of urban trees are not spread equitably across American communities. A national tree survey conducted by The Nature Conservancy, mapping urban tree canopy in 5,723 U.S. cities and towns reveals widespread inequity in tree cover between low- and high-income neighborhoods in U.S. cities, finding that, on average, there is 15.2% higher-tree cover in higher-income neighborhoods compared to lower-income areas. Furthermore, research by American Forests shows that the majority of communities of color have, on average, 33% less tree cover than the majority of white communities. This leads to higher temperatures, increased energy costs, fewer opportunities for outdoor recreation, and less resilience to storms and flooding in these communities. All these factors contribute to diminished health and well-being, particularly for communities of color, compared to white and/or affluent communities.

TREE EQUITY Disparities in tree cover exist between low- and high-income neighborhoods, as well as between communities of color and white communities. This inequity leads to various negative impacts on health and well-being. The orange areas in the images above show areas with poor tree equity scores (including low tree canopy). Source: American Forests’ Tree Equity Score tool for south Chicago (left) and St. Louis (right).

Treesilience: Community-Led Efforts To Increase & Maintain Urban Tree Cover

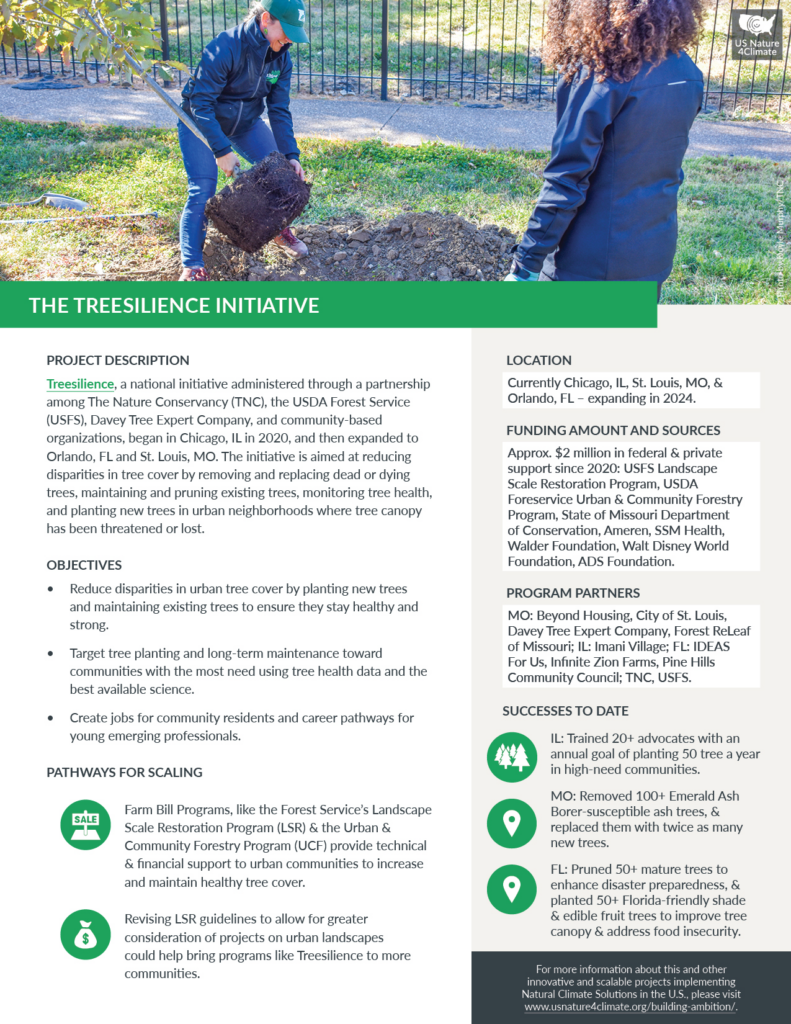

Treesilience, a national initiative administered through a partnership among The Nature Conservancy, the USDA Forest Service, Davey Tree Expert Company, and myriad community-based organizations, agencies, and industry partners, began in Chicago in 2020, and then spread to Orlando and St. Louis. The initiative is aimed at reducing disparities in tree cover and eliminating barriers to healthy tree canopy by removing and replacing dead or dying trees, maintaining and pruning existing trees, and planting new trees in urban neighborhoods where tree canopy has been threatened or lost. Importantly, the Treesilience program does not just focus on planting trees – it also helps maintain existing mature trees to ensure they remain healthy and strong. Efforts are targeted toward communities with the most need using the best available science. The program is administered jointly with community organizations – like Imani Village, Missouri ReLeaf, Beyond Housing, and Pine Hills Community Council – and when possible, young emerging professionals from within the community are engaged in the work, providing new pathways for careers in arboriculture.

Treesilience is currently active in Chicago, St. Louis, and Orlando, with plans to expand into additional U.S. cities and states. Read on to learn more about two of these programs.

Chicago: Urban Forestry with Imani Green Health Advocates & Treesilience

Rachel Patterson, a lifelong resident of the South Side of Chicago, initially believed that her Environmental Studies degree would not offer many career opportunities in her local area. However, her perspective changed when she discovered the Imani Green Health Advocates internship, the program through which Treesilience is implemented in Chicago.

This initiative, a collaboration between Imani Village, Trinity United Church of Christ, Advocate Health Care, Chicago Region Trees Initiative, The Morton Arboretum, The Nature Conservancy, and the USDA Forest Service, focuses on professional development and career training in three areas: environmental health, community health, and spiritual health. The advocates engage in outreach efforts within various neighborhoods on Chicago’s south and west sides, including Pullman, West Pullman, Cottage Grove Heights, Washington Heights, Roseland, and Chatham, addressing aspects of physical and mental health, landscape health, and spiritual well-being.

The Imani Green Health Advocates program is part of a larger, 23-acre, sustainable mixed-use development known as Imani Village, spearheaded by leaders and parishioners from Trinity United Church of Christ. Imani Village includes an urban farm, organic garden, NCAA sports complex, retail center, health clinic, youth development center, and community housing.

Sustainability and meaningful employment are central to Imani Village’s approach to community health, and this philosophy is reflected in the Imani Green Health Advocates program. The Advocates receive comprehensive training in urban forestry, tree health, and urban landscapes, with guidance from The Nature Conservancy and partners.

COMMUNITY ACTION The Imani Green Health Advocates program trains advocates in urban forestry and community health, with a focus on planting trees in high-need areas. The program provides career opportunities and improves community well-being. Photos by Joel Zavala/TNC.

Now in its fifth year, more than 20 advocates have been a part of the program, helping survey tree health and canopy in Chicago’s neighborhoods, identifying ideal locations for tree planting, and setting a goal of responsibly planting 50 trees per year in high-need communities. The tree-health findings are incorporated into Advocate Hospital’s community health needs assessment, and today Chicago residents can also request a tree or tree removal through the City’s CHI311 mobile app.

According to Patricia Eggleston, the Executive Director of Imani Village, the goal is to create a holistic and healthy lifestyle for the community, providing opportunities for meaningful careers and well-paid employment. As the program progresses, more permanent job placements are envisioned for the Advocates. For Rachel, the program expanded her resume through work with organizations like Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium and Audubon Great Lakes. She has also returned to the program as a guest presenter, sharing her story and conducting workshops with new cohorts of Advocates.

The collaborative efforts of Imani Village and its partners not only aim to create career opportunities for local residents but also to empower the community and improve overall health and well-being. With the continued growth of the Imani Green Health Advocates program and the amenities provided by Imani Village, the South Side of Chicago looks forward to becoming a vibrant and sustainable community for its residents.

Treesilience St. Louis: Growing a Resilient Tree Canopy

A healthy urban tree canopy provides a multitude of ecological, economic and social benefits that can enhance the overall quality of life. But threats to these trees – like life-threatening tree insects or pathogens – can weaken and even kill trees over time. These threats are worsening over time, largely due to climate change. In brief, these life-saving organisms go from benefit to burden, sometimes in a matter of a few years as can be the case for ash trees impacted by emerald ash borer. Frustratingly, costs associated with tree removal or mature tree pruning can be prohibitive for many. And, the longer dead or dying trees remain on one’s property, the greater the risk they pose, which can leave residents feeling less favorable toward trees, understandably. Hazardous tree removals or pruning can bring peace of mind to homeowners and communities, and perhaps even begin to restore relationships with trees over time.

That was the case for Dorothy Collins, who lives in the Pine Lawn neighborhood in north St. Louis County. In December 2021, the St. Louis Treesilience program officially kicked off in her front yard with the removal of a large sweetgum tree that had a huge stress fracture and was posing a threat to her house and more importantly, her safety.

For every tree removed in St. Louis, the team replants two trees in its place through a partnership with Forest ReLeaf of Missouri’s tree nursery.

The initiative focuses on areas where canopy is either threatened or already lost, and prioritizes communities where neighbors stand to gain the most from increased canopy, which is also the case for Collins. Communities in and around north St. Louis County and the City of St. Louis have high rates of air pollution and asthma-related hospitalizations.

“Community trees provide us significant benefits, and we believe that everyone deserves access not only to trees and greenspaces but to healthy trees and greenspaces,” Rachel Holmes, The Nature Conservancy’s urban forestry strategist, says. “Studies have shown that respiratory health can be improved by the expansion of healthy tree cover in areas with higher air pollution.”

The effects of Treesilience are lasting, but they start paying off immediately. At the program kick off, Collins shared her gratitude with the program partners for the removal and also her two new trees

“I’m thankful for everyone here and I’m relieved to get rid of that tree…I really am,” Collins said, adding that she is excited to watch her new trees grow.

Federal Support for Scaling Urban Forestry Program

Treesilience offers an important example of how combined federal funding sources that support both rural and urban forests can help advance the national climate agenda, overall, particularly through comprehensive reforestation. According to research shared by both American Forests and The Nature Conservancy through the Reforestation Hub, approximately 19% of the reforestation potential in the United States is in urban landscapes. Additionally, major tree insects and diseases are often discovered in urban trees and forests first.

Federal funding sources that support Treesilience – which is, at its core, a reforestation program – include a grant from the USDA Forest Service’s Landscape Scale Restoration (LSR) competitive grants program, which leverages both public and private resources to support collaborative, science-based restoration of forested landscapes, particularly in rural communities. These funds support Treesilience in North St. Louis County, where the population size of the 24 individual municipalities that make up the region qualify as ‘rural.’ Accordingly, Treesilience is an example of how LSR funding can not only support this urban forestry program, but also help meet broader U.S. reforestation goals.

Efforts are currently underway to revise the 2023 Farm Bill, the Congressional authority for the LSR grant program, to ensure that LSR applications for projects on urban landscapes may be fully considered alongside projects in rural communities, reflecting the need for a more comprehensive reforestation approach.

Programs like Imani Green Health Advocates (and/or organizations like Missouri ReLeaf) are also funded through generous support from the Forest Service’s Urban and Community Forestry (UCF) Program, which recently received a $1.5 billion boost in funding under the Inflation Reduction Act. The UCF Program provides technical, financial, and educational assistance to help urban communities increase and maintain healthy tree cover, with an emphasis on providing assistance to nature-deprived communities. This program is also authorized through the Farm Bill, making that particular legislation indispensable to nationwide efforts to expand tree cover and ensure the benefits of trees are enjoyed in all communities, while also tapping into the full potential of urban trees to address climate change.

Additional Resources

Download project fact sheet

(includes pathways for scaling)