Policymakers and land managers face difficult decisions in an increasingly uncertain climate future. Lands must support food and timber production, help buffer communities from extreme weather, provide space for people to live and recreate, support biodiversity and sequester carbon. Managing land to meet all these needs while confronting unpredictable weather and a growing global demand for food and wood requires thoughtful and proactive action.

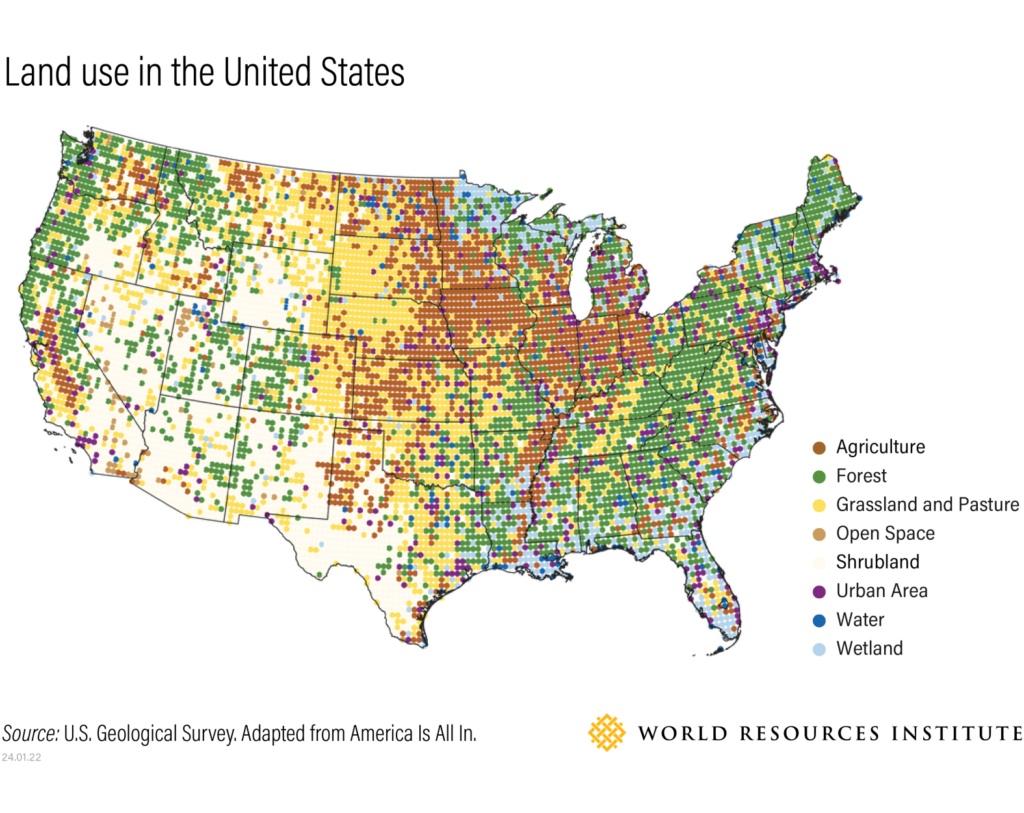

The U.S. lands sector, which includes forests, grasslands, wetlands, agricultural lands and agricultural operations, can remove carbon emissions to help curb the impacts of climate change, but it can also be a source of planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions. Activities like planting trees or conserving natural ecosystems increase what’s known as the land carbon sink, or the ability of land to sequester carbon. On the other hand, running farm equipment, fertilizing soil and plowing under native grasslands, releases greenhouse gases.

To reduce the most harmful impacts from climate change and support the U.S. target of reducing economy-wide net greenhouse gas emissions by 50% to 52% below 2005 levels by 2030, the land carbon sink needs to be increased and protected from future degradation, while lands-based emissions need to be decreased.

The Potential of US Lands

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, together with existing state forest and agricultural policies, are making critical investments in the resilience and health of the U.S. land base. But new analysis from America Is All In — a coalition of U.S. state and local leaders and organizations, including WRI — finds that the benefits from this investment are not yet secured. Effective implementation of climate-smart federal programs combined with increased state ambition and investment is required to protect and increase the land carbon sink.

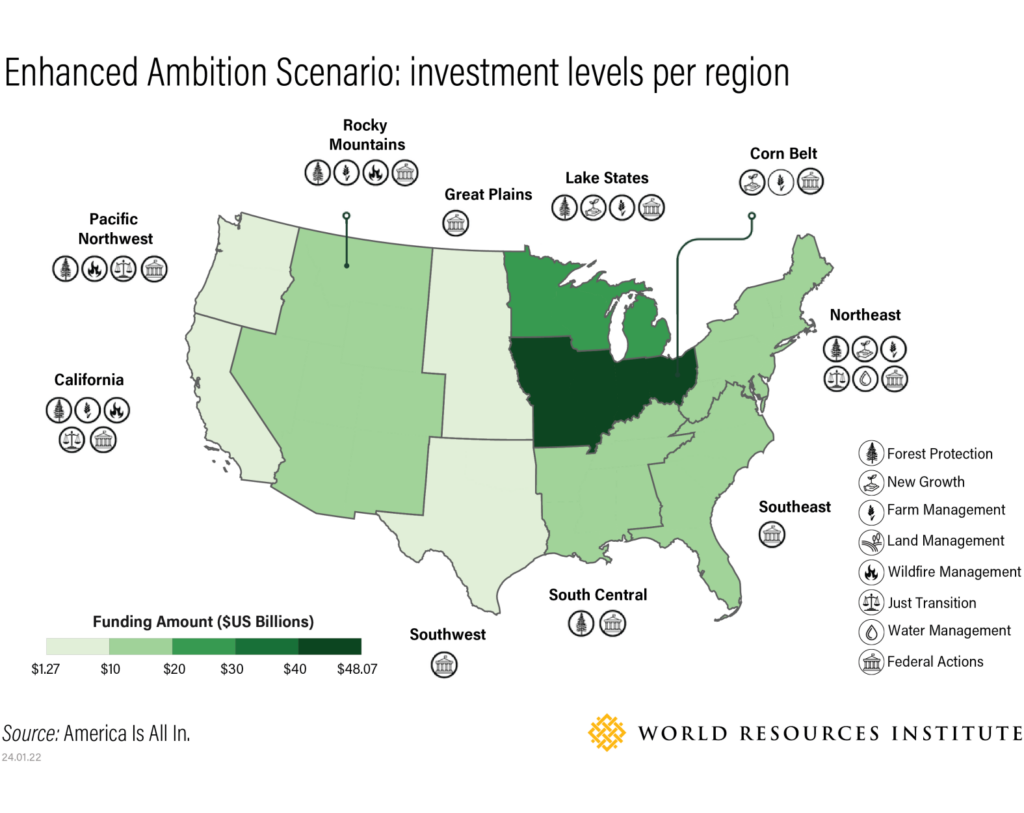

In 2021, U.S. lands sequestered approximately 750 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) per year, and agriculture emitted approximately 600 MtCO2e per year. Based on one set of models of the U.S. land sector, America Is All In finds that full implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act and other current federal and state policies, amounting to $42 billion of planned investment, would reduce agricultural emissions by about 8% or 48 MtCO2e per year over 2021 levels in 2035 and would increase the land carbon sink by about 1.5% or approximately 10 MtCO2e per year over 2021 levels in 2035. While a 1.5% increase is modest, implementation of current policies could help to reverse a projected decline in the land carbon sink.

With increased policy ambition and investment of approximately $160 billion in climate-smart forestry and agriculture the models find that the land carbon sink would increase by approximately 3%, or 24 MtCO2e per year in 2035. This high-climate ambition scenario would see a 13% reduction in agricultural emissions, or approximately 75 MtCO2e per year by 2035.

While America Is All In finds that these levels of land sector mitigation are enough to help the U.S. realize its climate goals alongside emissions reductions in other sectors, they do not realize the full potential of the land carbon sink. Other studies find much higher potential for reforestation, agricultural emissions reductions and other nature-based climate solutions, but maximizing the land carbon sink involves land use trade-offs. For example, planting trees can effectively sequester carbon, but planting new forests on large expanses of agricultural land could displace critical food production. Careful policymaking at the federal, state and local levels is needed to balance land use for food, fiber, biodiversity, climate mitigation and more.

What Should Land Managers and Policymakers Prioritize?

Protecting and increasing the land carbon sink will require an all-society effort. Federal funding like the Inflation Reduction Act can provide the foundation for action, but effective implementation takes place at the state and local level where the needs of ecosystems and communities are considered, while tradeoffs are weighed.

Despite historic levels of land sector funding in the Inflation Reduction Act, funding for many key projects is still limited and state and local leaders and their private sector and NGO partners need to prioritize actions that mitigate greenhouse gasses and increase resilience.

Here are four ways that policymakers, local leaders and land managers can prioritize strategies that will protect the land carbon sink and balance the many requirements for land use in the face of climate change.

1) Limit Conversion by Identifying Regional and Local Drivers of Land Use Change

While it is important to increase the land carbon sink, it is equally important to protect the carbon already stored in soils and vegetation. U.S. forests alone already contain about 60 gigatons of carbon, and they sequester an additional 700 MtCO2e each year. However, if forest ecosystems are severely damaged by logging or a natural disturbance, carbon stored in trees and soils is released to the atmosphere, and the ability of that forest to sequester carbon into the future may be diminished. This is also true of grassland and agricultural soils: Once carbon is lost, it takes intensive restoration and management to restore the carbon sink to pre-disturbance levels. This dynamic can be thought of as the “carbon cost” of clearing land for agriculture or development and not taking action to restore carbon stocks.

The factors that drive land use change vary regionally across the U.S. In areas where agriculture is a dominant industry, such as the Midwest, cropland expansion can drive the conversion of natural forest and grassland. Policies like the Renewable Fuel Standard that incentivize farmers to grow corn and soy for biofuels have contributed to the expansion of cropland into areas that are less productive and pose an outsized threat to habitat and biodiversity. Croplands have expanded by approximately 1 million acres per year between 2008 and 2016, leading to carbon emissions from the ecosystems that were converted.

The loss of cropland to commercial and residential development on some of the U.S.’s most productive soils is another driver of forest and grassland conversion. Urban expansion in many areas of the country displaces efficient agricultural production, requiring conversion to agriculture in other, less productive areas to compensate. The U.S. lost approximately 2,000 acres of prime farmland or ranchland every day between 2001 and 2016, and much of this land was converted to low-density urban development.

Forest loss due to land use change is an equally significant threat to natural carbon stores and ecosystem resilience. WRI’s Global Forest Watch finds that forest loss is most significant in the Northwest and Southeast regions of the U.S., and permanent deforestation is primarily driven by urbanization and commercial deforestation to accommodate demand for forest products. The U.S. lost 1.6 million hectares, or approximately 6,000 square miles of forest in 2022.

Policy approaches to curb land use change include:

- Implementing urban zoning practices that create more dense and livable cities and protect prime farmland. For example, the state of New York has created a Farmland Protection Program that helps farmers maintain agricultural activity.

- Making sure that biofuels and biomass policies include the true ‘carbon cost’ of biofuels to avoid incentivizing land use change and associated carbon emissions in the U.S. and abroad.

2) Build Resilience by Identifying Climate-related Factors that Threaten Local Ecosystems

Even though climate change affects all parts of the U.S., the key to managing ecosystems and lands for climate change is to identify the greatest health risks and then help them become resilient to change. Restoring an ecosystem often increases its carbon sink and resilient ecosystems and agricultural systems will reliably sequester carbon into the future.

Forests in Western and Southwestern U.S. states face an increased risk of extreme wildfire due, in part, to climate change, which can damage forests and reduce carbon sequestration capacity in the future. While wildfire mitigation treatments may decrease forest carbon stocks in the short- to medium-term, these treatments can safeguard forests in the long-term. Forests in the Rocky Mountain region are predicted to be a net source of carbon dioxide through 2070 without significant policy intervention, which underscores the urgent need to manage forests for wildfire resilience. Across the U.S., forests also face destruction by pests and pathogens, exacerbated by climate change, which one report has estimated will cost the U.S. 50 MtCO2e every year.

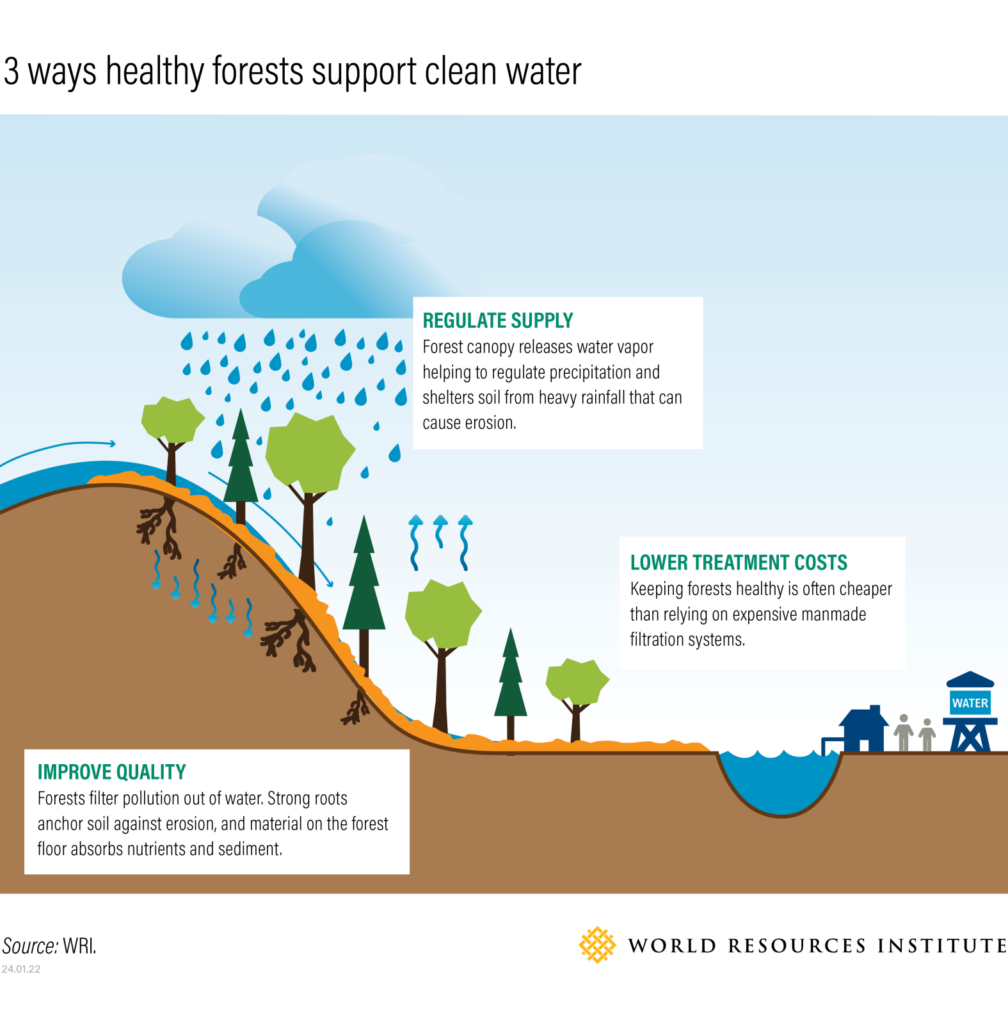

In agricultural areas, climate-related extreme weather like drought, heat and flooding threatens crop production. Practices that build soil health like cover cropping or reduced tillage can increase crop resilience to flooding and drought. Agroforestry, or the practice of incorporating trees and shrubs into agricultural and ranching systems, can protect fields from erosion, improve water quality, provide wildlife habitat and sequester carbon. It is important that policymakers continue to support farmers in adopting these resilience practices as well as in reducing agricultural emissions by using targeted fertilizer application, improving livestock feed and reducing food loss and waste.

Carbon sinks in coastal areas are also under threat due to climate change. Sea level rise can flood wetlands and prevent them from providing water quality benefits and habitat for young fish. In many places, development in coastal areas prevents wetlands from migrating in response to sea level rise, so wetland ecosystems are permanently lost. Coastal development can also lead to draining or fragmenting wetlands which causes them to release carbon and methane.

Policy approaches to increase ecosystem resilience include:

- Investing in risk mitigation treatments in areas with high risk of wildfires that improve forest health and resilience and reduce the risk of severe fire. For example, Colorado’s HB HB22-1011 created a grant program for local governments to undertake wildfire mitigation projects and education.

- Providing forest owners in areas where diseases and pests threaten forest health with financial support to increase the health and carbon sequestration potential. For example, New York created a Forestry Cost Share Grant Program.

- Establishing grant or cost-share programs to support farmers and ranchers in adopting resilience and emissions-reduction practices as the New Mexico Healthy Soils program has done.

- Planning to protect wetlands in the face of climate change as Oregon has done in its new Climate Resilience Package (HB 3409).

3) Plan for Economy-wide Decarbonization

In addition to sequestering carbon in soils and vegetation, lands will physically support economy-wide decarbonization. Building enough renewable power to meet U.S. climate goals will require 115,000 to 250,000 square miles of land to build wind and solar generation as well as new transmission lines to transport energy. But this doesn’t necessarily mean the land devoted to renewable energy can’t continue providing food and habitat.

Agrivoltaics, or the practice of using land for both solar generation and agriculture can provide shade for livestock and crops and provide farmers with an additional source of revenue. Livestock can also graze between wind turbines on rangelands in windy regions.

Local policymakers and land managers need to balance the protection of key wildlife habitat and farmland with the need for infrastructure build-out to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Without immediate and ambitious action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, climate change will continue to threaten the ability of lands to sequester carbon and provide services to communities.

Policy approaches to support responsible clean infrastructure buildout include:

- Adopting zoning ordinances or other planning methods to facilitate renewable energy buildout that protects and enhances the most productive agricultural areas and protects key habitats. New Hampshire’s Model Solar Zoning Ordinance offers a framework for leaders to consider community goals and impacts of solar siting to support better decision-making.

- Bringing together diverse interests to address barriers to large-scale solar projects and to balance the needs of nature, communities, and climate, as a group in California has done.

4) Increase Community Resilience by Identifying Opportunities for Green Infrastructure

As U.S. cities and towns experience increasing impacts from extreme weather, wildfire and sea level rise, the role of nature as a buffer has never been more important. Investing in nature as infrastructure to protect communities can mitigate the effects of extreme weather and provide water and air quality benefits. Many green infrastructure projects are also restoration and carbon sequestration projects. For example, restoring wetlands in and around cities can increase their ability to sequester carbon, filter water and protect coastal areas from erosion and storm surges.

Green infrastructure can save cities and utilities money by lowering water treatment costs and preventing weather-related damage, so innovative financing mechanisms are often available for these projects. WRI and Blue Forest’s Forest Resilience Bond helps the U.S. Forest Service, local water utilities and other partners secure private finance for forest resilience projects that could save utilities millions of dollars in the long term.

While green infrastructure can provide important services to communities, these services are not equitably distributed. Urban trees and parks can cool city streets, sequester carbon and improve air quality, but many low-income neighborhoods have far fewer trees than wealthier neighborhoods. Improving tree equity in these neighborhoods is critical to creating livable cities for all residents and support local livelihoods.

Policy approaches to support green infrastructure include:

- Adopting legislation that leverages private capital to fund restoration and environmental benefits like Maryland has done through its Conservation Finance Act.

- Creating grant programs to support urban tree planting as Wisconsin has done through its Regular Urban Forestry Grants.

- Accessing funds from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which delivered $43.3 billion for state water quality projects, and is distributed through the State Clean Water Revolving Loan Funds. Some states, such as Ohio, have had success leveraging these funds for stream restoration projects that improve water quality.

A People-centered Approach to Land Management

Land management strategies that support local livelihoods and well-being while delivering climate benefits are more likely to have sustained success in the long term. However, securing positive local outcomes for a project can be challenging because opinions about land management can be deeply tied to cultural, spiritual and economic values. Project funders and policymakers may also have expectations about the outcomes of a project that do not align with local desires or expectations. Research suggests that the following strategies can create successful projects and policies:

- Policy and project design should go beyond consulting local stakeholders — stakeholders should have continuous input starting from the initial stages of project development, as well as participate in project governance with clear dispute-resolution mechanisms in place. Initiatives should also involve all affected groups in designing and executing a project or policy, especially marginalized groups, to create durable and equitable outcomes.

- Government agencies should create collaborative resource management approaches to managing state and federal protected lands. This allows tribes or local stakeholders to co-manage land with agencies.

- Establishing Community Benefit Agreements can help guarantee local employment and other benefits to a community in exchange for their participation in a project.

- Projects that remove carbon can be incorporated into climate resilience and adaptation planning to ensure that projects are beneficial to communities. Resilience, adaptation and climate mitigation projects should include funding for measuring and monitoring carbon and other benefits to make sure projects have impact over time.

This article was originally published by the World Resources Institute. Access the original article here.

Further Reading

Explore our Decision-Makers Guide to Natural Climate Solutions to better understand the science behind these strategies and get tools to implement them.