Many rural counties in the United States face the dual challenges of lagging economic growth and increasingly severe effects of climate change. While urban areas are not uniformly prosperous and rural areas are not uniformly poor, rural communities on average lag behind their urban counterparts on most key economic indicators — from poverty rates to labor force participation. Rural areas represent 86% of persistent poverty counties in the U.S., while over 50% of rural Black residents live in economically distressed counties.

These challenges have been intensified by economic losses from the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated existing inequalities and highlighted urgent infrastructure needs. At the same time, catastrophic wildfires, record heatwaves, drought and other severe weather events linked to climate change threaten rural communities and livelihoods.

Addressing both the climate crisis and lagging economic vitality will require federal investment in building a new climate economy for rural America — one that reduces greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero while creating jobs, uplifting economically disadvantaged communities, and enhancing ecosystem services. This opportunity is already being realized in targeted regions (clean energy is a growing economic engine for many rural communities) and federal policymakers now have the opportunity to dramatically expand on this progress.

New WRI analysis finds that an annual federal investment of nearly $15 billion in key areas of the rural new climate economy would create hundreds of thousands of jobs in rural communities, add billions of dollars of value to rural economies, and generate millions in new tax revenues. This investment would help combat the economic stagnation confronting many rural areas and ensure that the benefits of the transition to a net-zero economy are widely distributed.

Understanding Rural Economic Opportunity by Area and Geography

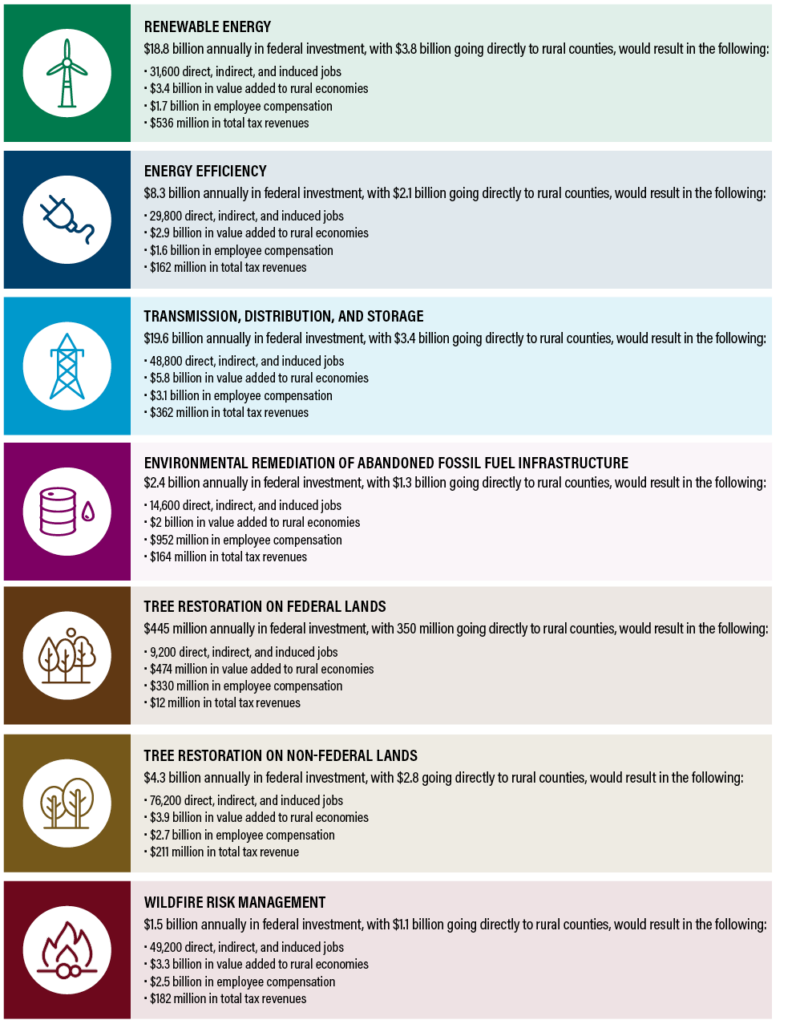

In this new paper, we analyzed the impact of $55 billion per year in federal investment in seven areas of the new climate economy over at least five years. These include investments in renewable energy; energy efficiency; transmission, distribution, and storage (TDS); environmental remediation of abandoned fossil fuel infrastructure; tree restoration on federal and non-federal lands; and wildfire risk management. An estimated $14.9 billion of that investment (27%) would be directed to rural America.

That investment would support nearly 260,000 direct, indirect and induced jobs for at least five years in rural counties (a total of 1.3 million job-years) and 740,000 jobs for five years in the country as a whole (a total of 3.7 million job-years). This equates to 17.5 jobs per $1 million invested in rural counties.

The results also indicate that new climate economy federal investment in rural areas would offer an attractive return on investment by adding $21.7 billion per year to rural economies for the first five years — $1.46 for every dollar invested. This includes $12.9 billion in employee compensation and $1.6 billion in federal, state and local tax revenues. The figure below shows the distribution of economic benefits across the seven investment areas.

Rural Economic Impacts by Investment Area (each year for first five years)

Job creation benefits would be widely dispersed across the country’s rural areas and vary by sector depending on regional economic factors. The top five states seeing the most significant impacts in terms of job creation relative to the size of local rural economies would be California, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Wyoming and Nevada.

California, New Mexico and Nevada would benefit most substantially from wildfire risk management investment. Massachusetts and Nevada, by contrast, would benefit largely from investments in renewable energy, energy efficiency, and grid transmission and distribution.

The analysis shows the geographic distribution of rural job creation potential (measured as jobs created in a rural county per 1,000 private sector workers, aggregated at the state level) from federal investment in each of the seven areas analyzed. Different investment areas naturally impact regions differently depending on local economic factors and where opportunities are located.

For instance, Massachusetts, California, Nevada, Maryland and Illinois would see the most job creation benefits from federal investments in renewable energy, while rural counties in Pennsylvania, Kansas, West Virginia, Kentucky and Wyoming would benefit most from investments in environmental remediation of orphaned oil and gas wells and abandoned coal mines. The latter is particularly important given that these are the same regions that have seen significant job losses due to the phasing out of coal generation. Investment in these regions can therefore help ensure a more just economic transition.

Rural counties in Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho and New Mexico are expected to see the highest levels of job creation from investment in tree restoration on federal lands, while those in Missouri, Ohio, South Dakota, Michigan and Wisconsin would benefit most from investment in tree restoration, including agroforestry, on state, local and private lands.

Direct and Indirect Benefits of Rural Investment in the New Climate Economy

Federal investments in the rural new climate economy would also provide benefits beyond job creation. Wind energy can help farmers and landowners earn money, providing additional income support and enhancing financial stability during lean times. Energy efficiency projects can help reduce energy bills for rural households by as much as 25%, representing more than $400 in annual household savings.

Investments in wildfire risk mitigation can help reduce the danger that catastrophic wildfires pose to rural communities and forests — an important point given that western wildfires are becoming more frequent and more destructive. In 2018 alone, wildfires in California cost the U.S. economy 0.7% of the nation’s annual GDP, highlighting the need to invest in measures that can help mitigate fire risks.

Local tax payments generated from these projects also provide much-needed revenue to rural communities for investing in new and improved infrastructure including roads, bridges and schools. In some cases, when a renewable energy project comes to a rural area, it is the largest single taxpayer in the county and accounts for a large share of the county’s budget.

Potential Impact on Economically Disadvantaged Rural Communities

To enable a new climate economy that supports economic wellbeing in all communities, federal investment in the seven areas described above must support the nation’s most economically disadvantaged rural communities.

The new climate economy opportunities described previously could create more than 118,000 jobs for at least five years (a total of 590,000 job-years) in these counties, resulting in over $9.8 billion added to these rural economies annually, including $5.9 billion in employee compensation and $685 million in total taxes.

Economically disadvantaged rural counties in California, Texas, New Mexico, Missouri and Kentucky stand to benefit the most in terms of total jobs supported by federal investment in the seven focus areas of this analysis.

Federal Investment in the New Climate Economy Could Significantly Benefit Economically Disadvantaged Rural Counties

While this job creation is significant, representing approximately 45% of job creation potential from investment in the seven areas of the new climate economy, more needs to be done to ensure economic benefits reach the areas where they are most needed.

Actions on this front could include: workforce training programs in the energy and land sectors with employment guarantees; measures to make clean energy affordable for low-income households; grant programs to support local businesses and nonprofit organizations; and requirements that new program designs be collaborative, inclusive and accessible to all workers.

Federal Policies Can Support a Rural New Climate Economy

The federal government has an opportunity to enact and expand policies that will drive investments in the new climate economy, creating jobs and bolstering rural economies in the process. Fully activating the opportunities analyzed in each of the seven areas would require a suite of federal policies, which could support a larger federal plan for rebuilding infrastructure and mitigating climate change.

The current push by Congress and the Biden administration to invest in the country’s ailing infrastructure and tackle the climate crisis represents the most promising political moment in years to support a new climate economy in rural America.

The proposed American Jobs Plan, representing the administration’s basis for negotiations with Congress on infrastructure, would provide historic levels of federal funding for places that have faced declining economic opportunities.

Several policy provisions of the American Jobs Plan — including investments in transmission lines, rural electric cooperatives to advance low-cost clean energy in rural communities, plugging orphan wells and cleaning up abandoned coal mines, and forest restoration — have the potential to create jobs and spur broad-based economic growth

The investments considered in our analysis, however, will likely not be sufficient on their own to recruit and train the workforce necessary to implement new climate economy pathways.

The policies recommended here will also need to include mechanisms to ensure that jobs created provide minimal barriers to entry, are well-paid, offer opportunities for stable employment and benefits, and support unionization. These components will help ensure that the new climate economy will not just create jobs, but sustain worker and community well-being and create equitable opportunities for all.

Federal policy opportunities by investment area

| Renewable energy | Extend investment tax credits and production tax credits for renewable energy Reauthorize tax incentives for clean energy manufacturing facilities through section 48C of the tax code Expand grant and loan programs that help rural communities finance renewable energy, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) |

| Energy efficiency | Extend tax incentives for efficiency upgrades in homes and residential buildings, including the existing homes tax credit (tax code sec. 25C) and new homes tax credit (sec. 45L) Extend tax incentives for efficiency upgrades in new and existing commercial buildings (sec. 179D) Boost funding level for block grant programs that channel money directly to state and local agencies for efficiency upgrades, including the Weatherization Assistance Program, State Energy Program, and Energy Efficiency Conservation Block Grants program, and create a comparable program for industrial facilities Expand grant and loan programs targeted at rural communities, including the USDA REAP program, Energy Efficiency Conservation Loan Program, and Rural Energy Savings Program |

| Transmission, distribution, and storage | Create tax credits to incentivize the build out of transmission projects that are regionally significant and can enable renewable energy integration on the grid and stand-alone energy storage technologies Reauthorize tax credits to incentivize domestic clean energy manufacturing facilities (sec. 48C) Reauthorize the Department of Energy’s Smart Grid Investment Grant program to promote investments in smart grid technologies Authorize the Department of Transportation to make transmission infrastructure projects, especially those that emphasize the integration of renewable energy, eligible under the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act loan guarantee program Expand loans and loan guarantees through USDA Electric Infrastructure Loan & Loan Guarantee to help finance transmission and distribution systems in rural areas Create a program to provide grants and technical assistance to rural electric cooperatives to deploy energy storage and microgrid technologies |

| Environmental remediation of abandoned fossil fuel infrastructure | Increase federal funding to clean up abandoned coal mine sites Create a new program for plugging and remediation at orphaned oil and gas well sites |

| Tree restoration on federal lands | Remove the funding cap on the Reforestation Trust Fund Increase appropriations for programs that fund restoration projects on federal land |

| Tree restoration on non-federal lands | Implement a refundable or transferable tax credit for natural carbon sequestration Enhance USDA conservation programs to incentivize natural carbon sequestration and reduce transaction costs for landowners, especially underserved landowners Provide additional funding through state and local grants and the State and Private Forestry programs of the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) |

Rural America’s Crucial Role in U.S. Climate Change Policies

Rural America will be indispensable in enabling the country to reach net-zero emissions: rural farmers, ranchers, and forest owners manage large segments of lands that hold enormous opportunities for climate mitigation. Rural areas are also crucial for clean energy development: 99% of all onshore wind capacity in the country is located in rural areas, as is the majority of utility-scale solar capacity.

U.S. climate policy, informed by the unique needs and context of rural America, can not only harness the power of rural communities to address climate change but also generate significant economic opportunities for these communities. This approach will be essential to helping the nation meet ambitious decarbonization goals while creating millions of good jobs across the country.

This article was originally published by the World Resources Institute.