Suzanne Radford knows the power of forests to help heal the sick and stressed. Those incredible capabilities enabled her to turn a passion for nature into a career. She now guides and coaches people in ways to use the sights, sounds and smells of the woods to create a sense of calm — something referred to as “forest bathing.”

Radford is one of many people starting to realize that trees and, more broadly, forests are an engine for job creation. More than 106,000 people in the United States work directly with forests in jobs, such as conservation scientist, forest manager and logger, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But many more have jobs that are linked to forests in less obvious ways. From science teachers to whiskey barrel makers to artists, people in myriad professions need forests and trees. In cities, park planners design urban oases that revolve around trees and the benefits they provide people. Sculptors carve wood reclaimed from old buildings into beautiful items that can be sold. And what would wildlife photographers do without forests that provide habitat for countless animals and birds?

Forests aren’t just something pretty to look at or walk through. They are the economic lifeblood for an increasing number of people in the United States.

Forest Bathing Guide

Lying on the trunk of an oak tree, Radford listens to a soundscape of birdsong and insects humming. A growing body of research shows that time spent in nature helps boost people’s moods and reduces anxiety and stress. Companies hire her as a nature coach to help their employees manage stress through time spent outdoors.

Suzanne Radford is a certified forest bathing guide and forest therapy practitioner. She helps people connect to nature through excursions in the Serra de Monchique mountain range of the Iberian Peninsula in Southern Portugal. Years ago, Radford discovered a secret waterfall in a forest she frequently visits. Now she offers her clients a chance to sit beside water, watch its movement and flow and listen as it cascades over the rocks. She encourages forest bathers to imagine the role the waterfall plays in feeding the mountain and surrounding forest, and to let the water wash over their hands and feet.

Production Arborist

Benyah Andressohn was 6 when he started climbing trees. Little did he know he would find his calling up in those branches. In high school he wanted a job that would pose a daily challenge, change the environment and allow him to use his brain. Becoming an arborist made perfect sense.

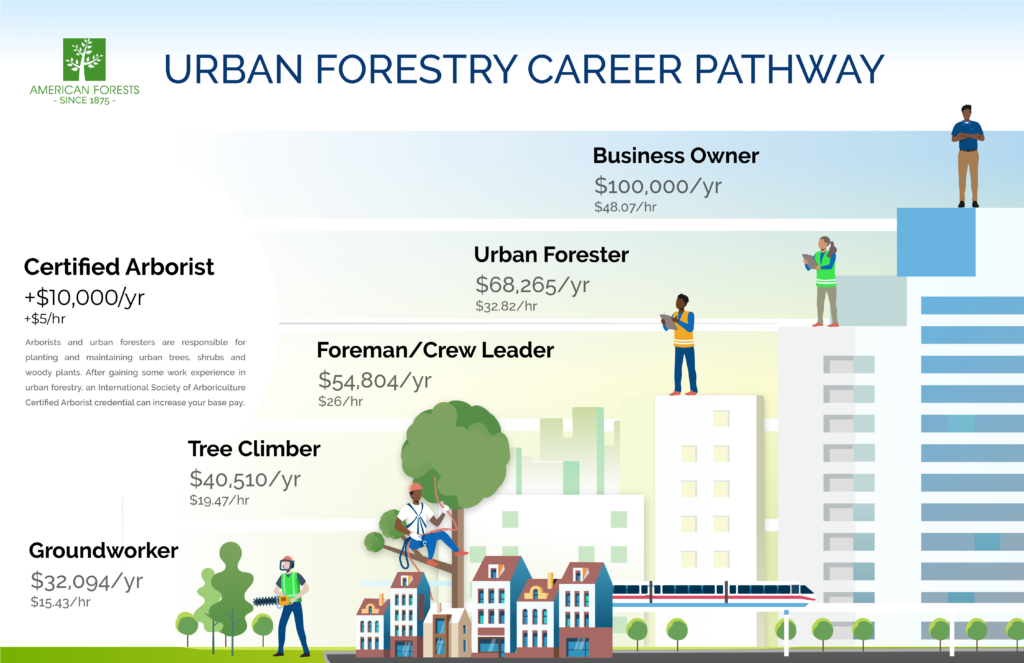

Andressohn works for True Tree Service in Miami, where he is a production arborist, trained to safely ascend and descend trees in order to care for them. Our cities need many more like him. Urban forestry is expected to see a 10% increase in job openings for entry-level positions by 2028.

Park Planner

Once they have identified a site for a park, planners like Clement Lau create a vision for the space. Here is his rendering of a pocket park proposed for Walnut Park, a community in Los Angeles County with very few trees and parks compared to other communities. Once grown, the trees included here will help improve air quality and cool down the neighborhood on hot days. Credit: Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation.

As a park planner for the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation, Clement Lau analyzes data, such as demographics, existing parkland, trees and transportation, to determine which unincorporated areas need parks the most. In places like Los Angeles County, parks are considered key infrastructure for quality of life, and trees are a major component of park planning.

Wood Sculptor

Canadian-based sculptor Patricia Aitkenhead’s carved animals make popular pendants and totems. But her business started with a classic debate: cats or dogs? As a way to settle the issue, she crafted a chess set comprised of a team of cats and a team of dogs. She chose breeds with traits she thought might fit their position on the board. Here, these pugs are the pawns.

Barrel Makers

Securing top and bottom barrel heads is one of the last touches in barrel production. Here, an employee at Kentucky Cooperage is placing the head hoop on a barrel.

Oak barrels being charred at Kentucky Cooperage in Lebanon, Ky. The charred American oak barrel is a cornerstone of American whiskey, and white oaks specifically are used in the aging of bourbon. Barrel makers char spirit barrels to create flavor, color, aroma, a char layer that acts as a filter, and to break down the wood cell walls so the spirit can extract flavors from the oak.

Wildlife Photographer

Richard Cronberg has been photographing wildlife for 40 years and sells his photos commercially in art shows, fundraising events, retail stores and online. Perhaps best known for his bird photos, Cronberg here is capturing a group of Snow and Ross’s Geese taking flight at Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge in California.

Here, Cronberg has photographed a northern pygmy owl, which make their homes in dense forests near streams in Canada, the United States and Mexico. Songbirds are the northern pygmy owl’s favorite meal, so it can often be found near a group of agitated songbirds that gather to scold it. Photo Credit: Richard Cronberg.

The tree swallow, found throughout much of North America, makes its nests in the cavities of trees. But when it emerges, this beautiful acrobatic bird chases flying insects through fields and wetlands. Photo Credit: Richard Cronberg.

This article was originally written for American Forests Magazine.