Inventories of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are a critical tool in the fight against climate change. GHG inventories allow entities like countries, states, cities and businesses to measure how much progress they are making toward meeting emissions-reduction targets, such as those set under the Paris Climate Agreement. Climate policies at all levels of government are also informed by data in GHG inventories.

The U.S. Climate Alliance has facilitated ambitious state-level action on climate change since 2017, when the United States government announced its intent to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. To support states’ technical needs in building and implementing these climate action plans — including by developing robust GHG inventories — the U.S. Climate Alliance has convened an “Impact Partnership” of nonprofit organizations with relevant expertise, including WRI. Through that partnership, WRI and the U.S. Climate Alliance have published a guide for states to develop and improve their GHG inventories with an eye toward one particular sector that has often been shortchanged: natural and working lands (NWL). But to understand why a state-level guide specific to land-based GHG inventories is needed, it’s important to first know what a GHG inventory is, why inventories are produced and how they are created.

Inventory Basics: What, Why and How

1. What is a GHG inventory?

An inventory accounts for all human-caused emissions and removals of GHGs associated with a specific entity. The inventory essentially acts as a climate change balance sheet, tracking the total volume of GHG emitted from sources like fossil fuel consumption and agricultural production alongside the volume of GHG removed by sequestration in plants and soils or through technological means. Good inventories transparently report their data sources and methodologies so the calculations and assumptions that underlie GHG estimates are clear. Typically, entities produce GHG inventories annually or on some other regular schedule to monitor changes in their GHG emissions and removals over time.

2. Why produce a GHG inventory?

As the saying goes, “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.” Measuring GHG emissions and removals through GHG inventories is therefore a necessary first step to manage our collective carbon footprint. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has required participating nations, including the United States, to produce and submit annual GHG inventories since 1997 to measure progress toward international climate goals. In more recent years, many U.S. states have voluntarily published their own GHG inventories to inform development of state climate action plans and provide accountability for their emissions reduction goals.

With the U.S. government and the U.S. Climate Alliance’s recent commitment to reduce collective net GHG emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels by 2030 and achieve overall net-zero GHG emissions no later than 2050, the accuracy and comprehensiveness of these inventories has never been more paramount. Achieving net-zero at both the federal and state levels will require concerted action — not only to reduce emissions throughout the economy, but also to increase carbon removals, including the management of natural and working lands.

NWL, which include forests, croplands, grasslands, wetlands and urban trees and soils, make up the only sector in the U.S. that removes more carbon from the atmosphere than it emits, reducing total U.S. emissions by nearly 800 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year, or about 12% of U.S. gross emissions. This increase in land-based carbon storage, which overwhelmingly comes from forest growth, offsets the 10% of gross U.S. emissions from agricultural production. Emissions from agricultural production, which includes soil fertilization, manure management, enteric fermentation and other sources related to crop and livestock cultivation, are typically considered separately from NWL in GHG inventories.

With additional investment in conservation, restoration and land management, the amount of carbon removed by NWL in the U.S. can grow significantly, offsetting a greater portion of U.S. gross emissions and moving the U.S. closer to meeting its ambitious GHG reduction targets.

3. How are Natural and Working Lands included in GHG inventories?

Unlike GHG emissions from fossil fuel combustion, which are easily tracked through publicly reported energy use data, emissions and removals from NWL are more difficult to measure. These emissions and removals are occurring constantly over millions of acres due to farming and forestry operations alongside natural ecosystem carbon cycles, making universal monitoring very challenging. In many cases, scientists are also still refining our understanding of how land management practices like forest restoration or conservation tillage impact GHG flows in those environments. Therefore, GHG inventories typically rely on sample data to estimate the area of NWL within certain classifications and GHG models or approximate “emission factors” to estimate GHG emissions and removals as a function of area.

These challenges illustrate why estimates of land-based emissions and removals in GHG inventories are typically much more uncertain than energy emissions. Contributors to the uncertainty include:

- Timeliness of data inputs (how long ago data were collected).

- Spatial and temporal resolution of inventory data (how finely data can be mapped over space and time).

- Gaps in inventory coverage (which sources of emissions and removals are omitted).

- Error in GHG models and emission factors (how accurately the calculations mirror real-world emissions and removals).

These challenges are compounded at the state level, where most states lack the resources to develop their own inventories and have had to depend on federal data and tools with significant limitations. Many states, for example, use the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) State Inventory Tool (SIT), which applies the same methods and data sources used for EPA’s National GHG Inventory at the state level. However, much of the data on land-based emissions and removals used in the National Inventory is not available at the state level, so SIT has relied on older and less accurate data to fill gaps. SIT also does not publish measures of uncertainty. For these reasons, many states have opted to leave NWL out of their GHG inventories entirely, while others that do include SIT estimates for that sector have cautioned against relying on them for goal-setting or policymaking purposes.

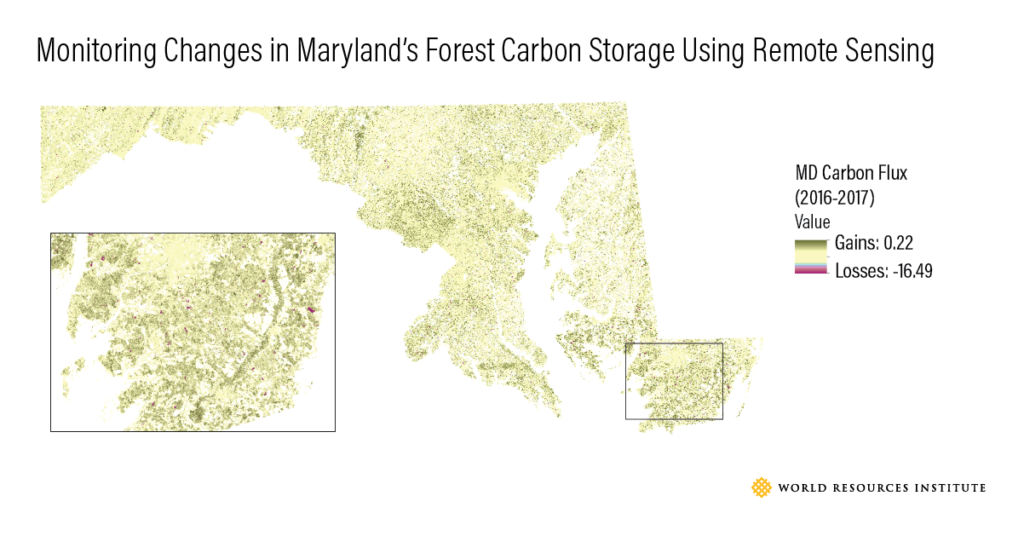

How to Improve GHG Inventories for Natural and Working Lands

Fortunately, a mix of current and emerging datasets and technologies can help states improve their estimates of GHG emissions and removals from NWL. These inventory improvement options have the potential to not only address specific limitations of SIT, but could also provide even more accurate and granular information than the National Inventory. More accurate, more transparent and higher resolution estimates of NWL emissions and removals can help state governments set robust climate targets specifically for NWL in addition to measuring progress toward existing goals, informing new climate policies and underlying plans for climate-smart land management.

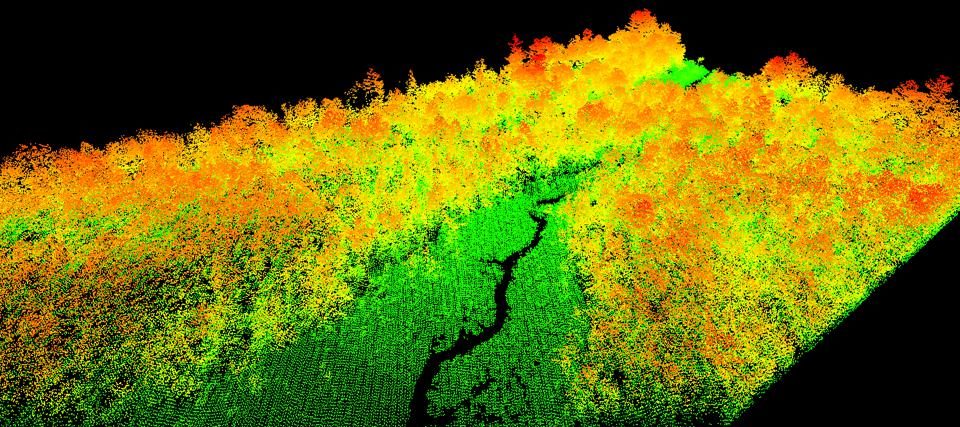

Most options for states to improve the NWL data in their inventories follow one or both of two strategies. Either the state can collect new field measurement data, for example by adding to the Forest Service’s network of forest inventory plots or by measuring carbon in soil samples; or the state can use remote sensing tools like LiDAR and satellite imagery to complement existing data from field measurements.

All inventory improvements come with costs, so states will need to prioritize improvements based on their potential impact, policy relevance and feasibility. WRI’s Guide to NWL Inventory Improvements walks states through available options for improving inventory data for each land use type included in a NWL inventory along with factors to consider in deciding where to prioritize limited state resources.

Several U.S. states have already begun to implement innovations in their NWL inventories. In March 2021, Maryland committed to replace forest data from SIT with a new inventory method that uses high-resolution LiDAR and satellite imagery to model forest carbon over time, based on research conducted by the University of Maryland and WRI under a grant from the U.S. Climate Alliance. Across the country, California, Oregon and Washington have all worked with the Forest Service to develop state-specific estimates of carbon in wood products, allowing them to update the decades-old data in SIT. Even farther west, Hawai’i partnered with the U.S. Geological Survey to create its first NWL inventory, as most of the federal datasets that underlie SIT did not include data for Hawai’i.

These are just a few of the exciting innovations states are pursuing to improve their inventories. But many other states lack the resources or capacity to take on their own improvement projects and the need for more national coordination and consistent, quality GHG estimation tools and NWL datasets that can be utilized by every state remains. Therefore, it’s clear that federal investment is paramount. Recent federal efforts, like the publication of new Forest Service research in 2020 that quantified forest carbon emissions and removals at the state level, help move the ball forward — but there is still much room for improvement.

3 Ways the Federal Government Can Help Improve State Inventories

The Guide to NWL Inventory Improvements identified three key needs across states, spanning the key NWL systems of forests, agricultural soils and wetlands, where the federal government would be best positioned to lead inventory improvements. With President Biden restoring the United States to a leadership role on climate action hours after becoming president, these opportunities offer common sense steps to advance the role of NWL in climate action plans at all levels of government.

1. Develop a national remote sensing-based forest and land use inventory.

The National GHG Inventory and SIT rely on data from the Forest Service’s Forest Inventory & Analysis program (FIA), which is among the most comprehensive forest monitoring systems in the world, but was not designed to meet current demands for precise carbon data at a variety of scales. Using federal data products like Landsat and GEDI, the federal government could complement FIA with remote sensing data to map and model carbon emissions and removals across the landscape, reducing uncertainty in forest carbon estimates.

2. Monitor soil carbon through national field networks.

Carbon sequestration in agricultural soils is currently modeled, not measured, to calculate GHG estimates in the National Inventory and SIT, leading to uncertainty of over 1,000% nationally for some soil carbon removal estimates. Regular, systematic collection of soil carbon field measurements through the federal National Resources Inventory (NRI) could help refine models and reduce this uncertainty dramatically. The National Academies of Sciences has estimated the cost of this endeavor at just $5 million per year.

3. Develop a national spatial inventory of GHG emissions in wetlands.

Wetlands are among the least-understood contributors to GHG emissions from NWL. No consistent data on wetland GHG emissions exist at the state level, and even the National Inventory does not account for GHG emissions from most terrestrial, or freshwater, wetlands. The federal government could improve this understanding by creating a high-resolution spatial dataset to monitor changes in wetland extent, vegetation and management, incorporating existing data from the Coastal Change Analysis Program (C-CAP) and National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) where relevant, and pairing it with a network of field plots to derive regionally-specific emission factors for different wetland types.

Helping States Lead the Way on GHG Inventories for Natural and Working Lands

For the last four years, states have been forging ahead with climate action even as the federal government rolled back environmental regulations and withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement. States in the U.S. Climate Alliance have led the way in linking land management to climate change mitigation through the NWL Challenge, but they need better data and inventory methods in order to act boldly and effectively. Some states have jumped out ahead by experimenting with new methods for carbon monitoring in NWL, but federal action has the unique ability to “lift all boats” when it comes to data quality and consistency. As it now re-engages on climate change at home and abroad, the federal government has an opportunity to put wind under the wings of state leadership by investing in the tools they need to monitor and manage land for a climate-friendly future.

Alex Rudee is a Manager for U.S. Natural Climate Solutions at World Resources Institute. Jenn Phillips is a Senior Policy Advisor for Natural and Working Lands and Resilience at U.S. Climate Alliance. Both Alex and Jenn serve on the U.S. Nature4Climate steering committee.