Climate positive is a summit that very few companies are yet pursuing. Blazing this new trail will not be easy. Yet, if we don’t carve a new, bold path for our industry and others to follow, we will ultimately fail to protect the outdoor experience upon which our businesses and many livelihoods around the globe depend. Our customers, consumers and employees are asking this of us… Now, united around this bold new goal and commitments, the outdoor industry through the Climate Action Corps – is poised to lead by example.

The world faces an urgent climate change problem caused by human activity, namely the burning of fossil fuels and the destruction of natural ecosystems. The Earth has already warmed by 1 degree since the 19th century, and to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, we must limit warming to 1.5 degrees. Global climate experts agree: if we don’t curb emissions immediately, the results will be catastrophic for life on Earth. To avoid that, the world must cut emissions in half by 2030 and reach net-zero emissions by 2050 (that is, any remaining emissions are neutralized by the equivalent carbon removals).

The bottom line: Every government, business and individual must act. And we believe the outdoor industry must lead.

Climate change is already threatening the $778 billion outdoor industry and outdoor participation everywhere. Ski seasons dwindle and resorts struggle to operate profitably; warmer streams, drought and fire diminish hunting and fishing activity; and kids and families shutter indoors throughout the West as wildfire-polluted skies force cancelled camping trips and hiking excursions, or, much worse – devastate entire communities. Extreme weather-related events are also harming people and communities across the globe that often make our products, while these same events disrupt the supply chains we depend on. With so much at stake, the outdoor industry must be at the forefront of transformation and innovation toward a low-carbon economy. Outdoor Industry Association (OIA), as the North American industry’s trade association with a mission to ensure a thriving outdoor industry for generations to come, has a primary responsibility to support its members and the industry to rise to face this challenge.

The Outdoor Industry’s Opportunity To Lead

As individual companies, the choices we make – from renewable energy to power our operations, to low-carbon materials and production processes to make our products, to enabling the reuse of our gear – can have an impact. But as an industry, we can be a significant force in reversing the impacts of climate change. Our collective efforts can scale innovations, activate millions of consumers, drive policy and create a model for other sectors to follow. Our industry has a history of innovation, leading with our values, and stewarding the planet. We know that our employees and our customers are expecting us to be part of the climate solution. We also have a history of coming together to tackle hard problems.

Many outdoor companies are already taking meaningful climate action – measuring their carbon footprints, setting greenhouse gas reduction targets, and neutralizing the emissions they cannot yet reduce. But we recognize these actions by a few leaders among us is not enough. We can do better. We need to catalyze bold, widespread climate action across our industry and beyond by forging a new path. Rather than simply reducing harmful practices, we can bring forward regenerative ones. Instead of just doing “less bad,” we can create “more good” for society and the environment. We can set aggressive science-based reduction targets that we are not 100% certain how to achieve – acknowledging the “innovation gap” between what can be modeled, and what’s actually required. We can remove carbon from the atmosphere through solutions that also restore and conserve nature, increase outdoor recreation opportunities for all, and build climate-resilient communities. We can advance a just transition to the clean energy economy. In doing so, we go beyond simply decreasing our negative impact to creating positive impact.

For these reasons, OIA created the Climate Action Corps in early 2020, which has since grown to more 100 members representing more than $25 billion in annual sales revenue.

With input from our members, Board of Directors, Sustainability Advisory Council and external experts over the past year, we are excited to announce a new aspiration to become the first climate positive industry by 2030, creating a bold example for others around the world to follow. We chose an ambitious but achievable target because we are leaders in the mountains, in our R&D departments and in the marketplace, and we believe we can reach this summit by working together. To make this an achievable goal for our members, OIA is assembling resources to guide and support each step of the journey.

What Does “Climate Positive” Mean?

Global consensus is still emerging, and we have grounded our own definition of “climate positive” in work being done by climate experts and NGOs and will continue to evolve this working definition as consensus emerges.

Our working definition: Climate positive means to reduce your greenhouse gas emissions in line with a science-based target (SBT) that addresses all scopes, to remove even more GHG from the atmosphere than you emit, and to advocate for broader systemic change.

Climate scientists agree that even with aggressive reductions in emissions, carbon removal—the process of extracting carbon dioxide from the air and storing it—will be crucial to avoiding the most catastrophic impacts of climate change. We also believe climate positive brings an opportunity for our industry to promote equity and climate justice. We will continue to seek the input of experts and leaders in carbon accounting, climate science and the climate justice movement – as well as our own member companies – to ensure our approach is bold yet pragmatic, science-based, inclusive and equitable, and drives environmental, societal and business value.

With this bold goal in place and a community of 100+ outdoor companies engaged in the Corps, we are moving quickly to establish a credible, practical pathway, supporting resources, and interim milestones that will guide and accelerate progress and lead our industry to climate positive by 2030.

The Path To Climate Positive

Measure + Plan | Reduce + Remove | Advocate + Engage | Share

Climate Action Corps members commit to the following actions, with a new member requirement as of 2021 to set a science-based target that addresses all scopes within two years of joining:

Measure + Plan.

Build a company-specific action plan. Calculate your entire carbon footprint (accounting for scopes 1-3, as defined by the GHG Protocol). Base your measurements on more and more primary data over time. Set a science-based target (SBT) that addresses all scopes within two years of joining (new requirement).

Society has not yet committed sufficiently to reduce emissions, and science-based targets are the only way to ensure carbon reduction at the individual organization level happens at the pace and scale required to meet the global 1.5 degree warming limit. OIA will release new Guidebook content and training resources to help members tackle challenging “scope 3” measurement in particular, as well as resources to support science-based target setting in line with the Science Based Target Initiative criteria in 2021 (though members will not be required to set SBTi-approved targets, we encourage companies to seek this level of 3rd party validation).

Reduce + Remove.

Take immediate and ongoing action to drive down carbon emissions in line with your SBT. Compensate for remaining emissions by investing in projects with a quantifiable climate benefit (e.g., through direct investment or purchasing offsets) that ideally remove carbon from the atmosphere.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in line with science is a critical part of any business’s climate strategy – no matter the size or structure. The market will demand our member brands have made meaningful reductions within five years. Because most of our industry’s GHG emissions are in the supply chain, implementing reductions has a long horizon. The Climate Action Corps puts forward these guiding principles for reduction: run cleaner, transport smarter, make better, and grow creatively, and provides resources as well as hosts collaborative projects (“CoLabs”) to drive reductions in accordance with these principles. Work will expand in 2021 to support all Climate Action Corps members to be on track to meet their SBTs by 2025. Changing the methods and materials for making our industry’s products will be challenging. Success will be far more likely working together to solve problems and leverage buying power. OIA is well-positioned to facilitate this kind of collaboration between our member companies, in partnership with on-the-ground organizations and experts.

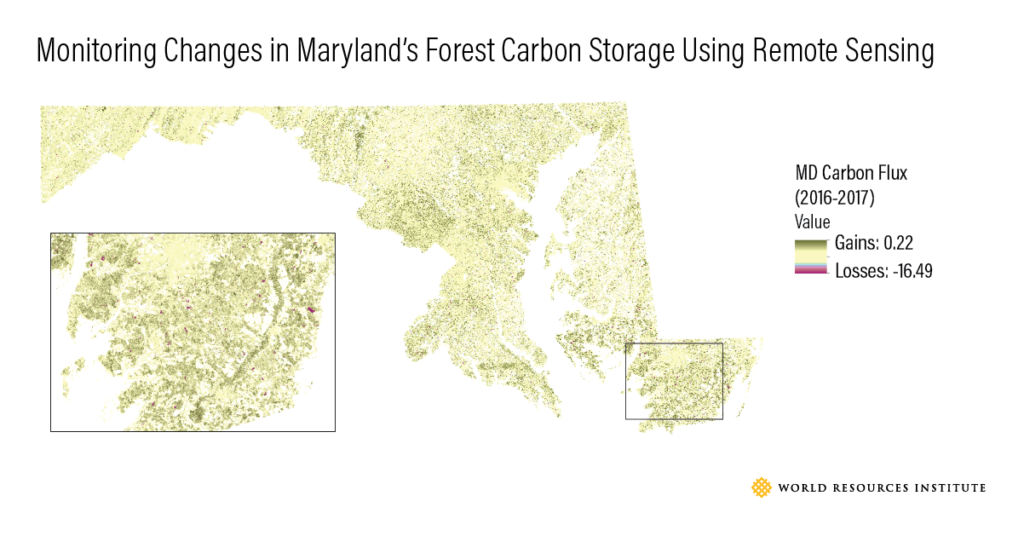

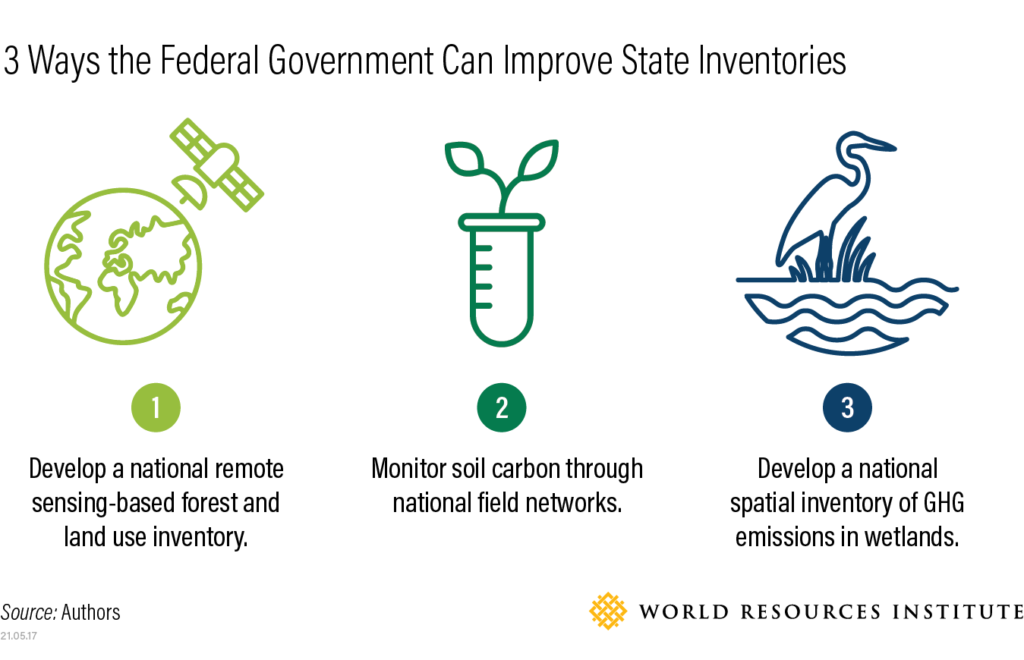

But reductions alone cannot achieve net-zero or climate positive – and science is also clear that reductions alone will not be enough to limit warming to 1.5 degrees by mid-century. We also have to remove excess carbon from the atmosphere. Building on its long history of land and water conservation advocacy, the outdoor industry is in a unique position to galvanize investment in nature-based carbon removals or “sinks” – forests, farms, and grasslands – that may also provide recreational benefits for our consumers and economic benefits for landowners, farmers and their communities.

As businesses progress along reduction pathways, emissions that cannot be reduced will remain. We acknowledge these difficult-to-abate emissions have a negative impact on society, the environment, and outdoor businesses – in other words, they have a cost. Therefore, we believe they should: 1) Be priced into doing business – establishing an internal price on carbon creates an incentive for businesses to drive further reductions to decrease cost, and 2) Be compensated for by removing the equivalent amount of carbon from the atmosphere in the transition to climate positive – nature-based carbon sequestration measures are preferred because they also have the potential to create societal co-benefits that align with outdoor industry values, from creating shade in heat-stressed urban areas to restoring forest ecosystems.

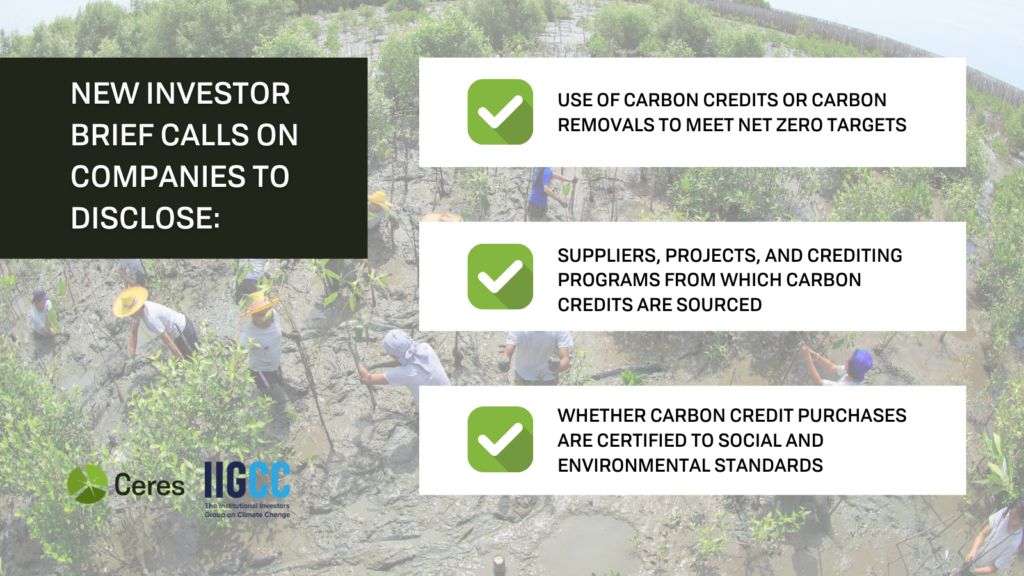

Carbon offsets, or voluntary carbon credits, provide one means to accomplish removals, provided they meet standards for high quality (see Guidebook). Yet, we go into this clear-eyed on the realities and challenges: the carbon removals market is nascent and limited today. We have an opportunity to contribute to growth, rigor and innovation in this space. It’s also important to acknowledge that offsets alone are not an appropriate carbon management strategy and should be used in addition to a science-aligned reduction target and abatement strategy. In other words, a comprehensive climate strategy includes both reducing and removing carbon. Both are challenging, but necessary.

Advocate + Engage.

Advocate for critical, systemic policy change and engage your consumers and business partners. Recognize and reward climate-leading practices with your vendors and supply chain partners.

The systemic transformation required to meet the global targets outlined by the scientific community requires action by all countries, and all levels of government. Climate Action Corps members bring a unique and powerful business voice to the climate policy landscape. OIA and its partners provide advocacy opportunities annually (op-eds, fly-ins, testimony, signons letters, etc.) that advance our climate policy priorities, which include: incentivizing businesses that take bold climate action, accelerating an equitable transition to renewable energy, advancing natural climate solutions and supporting green infrastructure like more parks and paths to build low-carbon, climate-resilient communities.

In addition, our collective millions of employees and consumers have the power through their individual actions to have a remarkable cumulative impact as both citizen advocates and in reducing their own footprints. Trusted outdoor brands can inspire, empower and even enable consumers to take action – from driving to their favorite campsites or ski areas in electric vehicles, to converting their homes to renewable energy, to making their voices heard with policymakers – among other actions.

Last but not least, in addition to driving policy solutions and engaging our consumers, Climate Action Corps members commit to recognizing and rewarding climate-leading actions with their vendors. Retailers have a critical role as “choice editors” in assorting, promoting, and otherwise showing preference toward brands that are progressing in meaningful, measurable ways – bringing more relevant products and innovations to consumers who increasingly demand them.

Share Our Progress.

We use transparency to maintain credibility and drive accountability. Every Climate Action Corps member is required to submit an Annual Progress Report each April to be posted publicly on OIA’s web site, as well as used to aggregate data to demonstrate our collective impact through our annual “Path to Climate Positive” report.

OIA Sustainability Advisory Council Members

Matt Thurston, REI (Chair)

Libby Sommer, Bolt Threads

Guru Larson, Columbia Sportswear

Danielle Cresswell, Klean Kanteen

Theresa Conn, NEMO Equipment

John Stokes, New Balance

Kim Drenner, Patagonia

JJ Trout, PeopleForBikes

Kristen Bandurski, Red Wing Shoe Co.

Alicia Chin, Smarwool

Marie Mawe, W.L. Gore

Jennifer Silberman, YETI

OIA Sustainable Business Innovation Board Committee Members

Cam Brensinger, NEMO Equipment (Chair)

Jonathan Cedar, Biolite

Alison Hill, LifeStraw

Bruce Old, Patagonia

Sean Cady, VF Corp

This statement originally appeared on outdoorindustry.org.