I am writing this article at a pivotal moment for America. The country is emerging from a global pandemic that has magnified health inequities, especially in terms of income and race. And climate change is moving faster than expected. During one week in June, for example, there were killer heat waves in the cool Pacific Northwest and flooding in the Great Lakes region.

These elevated stakes help explain why American Forests has made a commitment to keeping score — which we hope will lead to more people taking action to advance social equity and slow climate change, in part through the power of trees.

This started with the launch of our Tree Equity Score in June. This tool, the first of its kind, gives a neighborhood-by-neighborhood and municipal-level assessment of tree cover in every urban area across America. It overlays data that shows where the lack of trees most strongly puts people at risk from extreme heat, air pollution and other climate- fueled threats.

Collectively, the scores tell several compelling stories. For instance, on average, the lowest income neighborhoods have 41% less tree cover than high-income neighborhoods, and neighborhoods with a majority of residents of color have 33% less tree cover than majority white neighborhoods. This has life or death consequences, given that neighborhoods with little to no tree cover can be 10 degrees hotter than the city average during the day, and even more at night. In these same places, there is a higher percentage of people with elevated risk factors, such as heat-related illnesses and deaths because of lack of air conditioning.

That’s where Tree Equity Score comes in. By naming and framing this dangerous inequity with data and putting it online for all to see and explore, we have brought unprecedented attention to the importance of trees in advancing social equity. This includes a major feature in the New York Times, co-authored by our own Ian Leahy, vice president of urban forestry.

But this tool does much more than just identify the problem. It is as easy to use as a smart phone, making it simple for anyone, from city leaders to city residents, to calculate how many trees are needed for a city to achieve Tree Equity in every neighborhood. They also can see the economic and environmental benefits that would be generated, such as the tons of air pollution removed annually and number of jobs supported.

As evidence that Tree Equity Score can catalyze meaningful change, the Phoenix City Council voted in April to achieve Tree Equity in every one of the city’s neighborhoods by 2030. Other cities are following suit. And Congressional leaders, such as U.S. Senator Cory Booker (D-N.J.) and U.S. Representative Doris Matsui (D-Calif.), are using it to make the case for unprecedented federal investment in urban trees and forests.

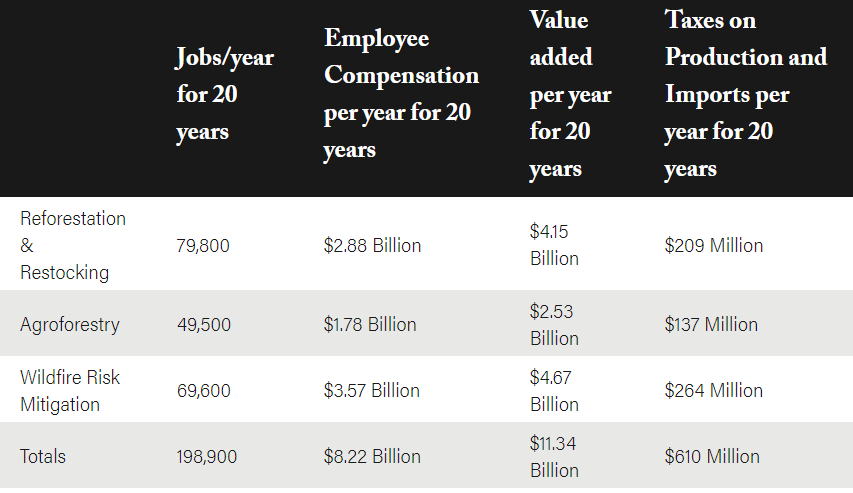

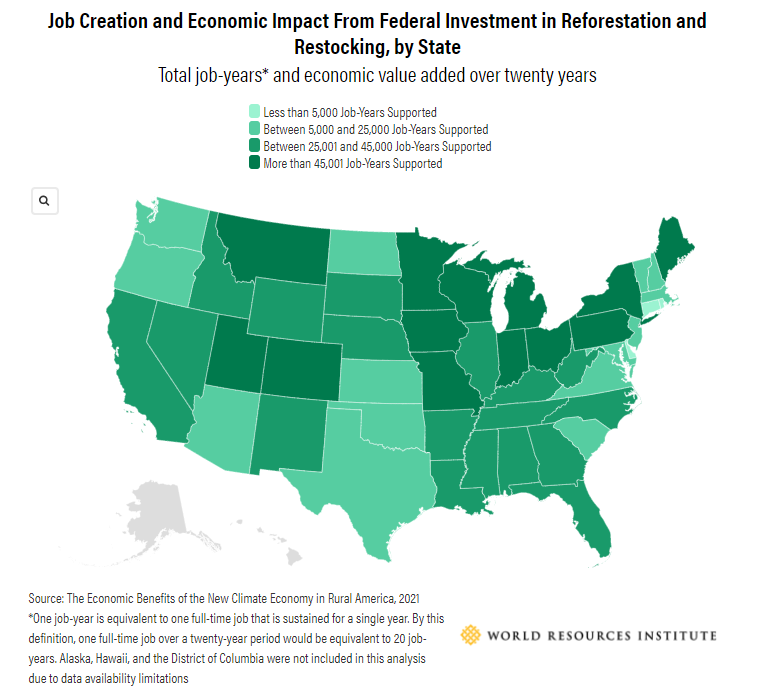

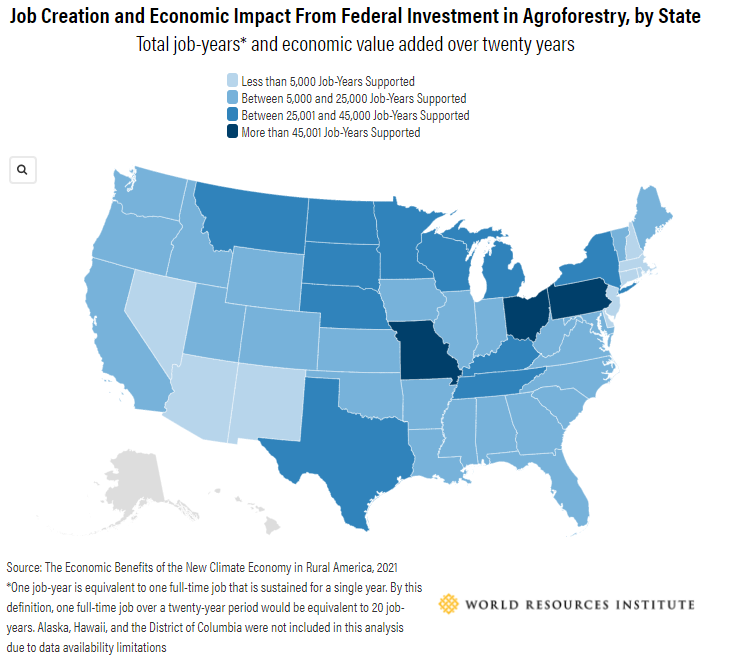

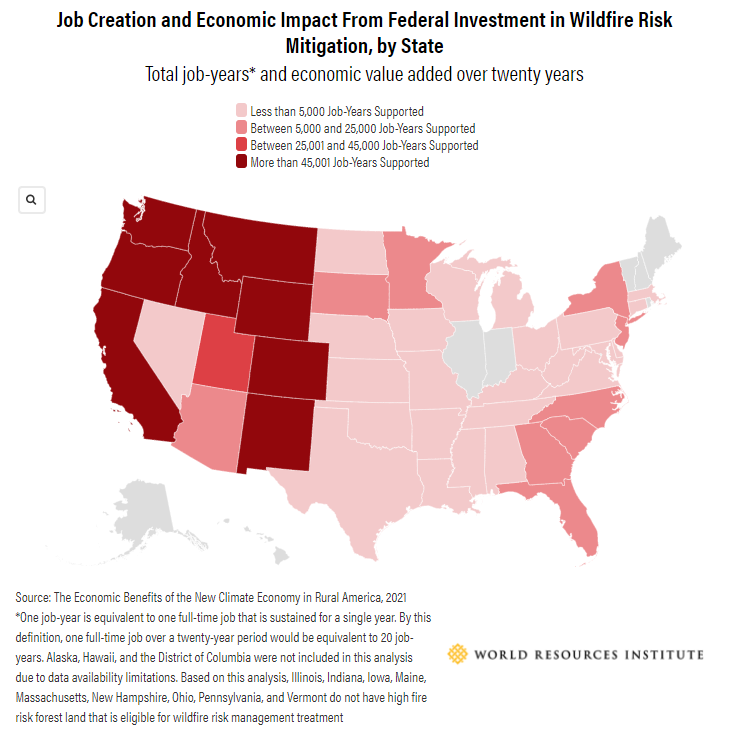

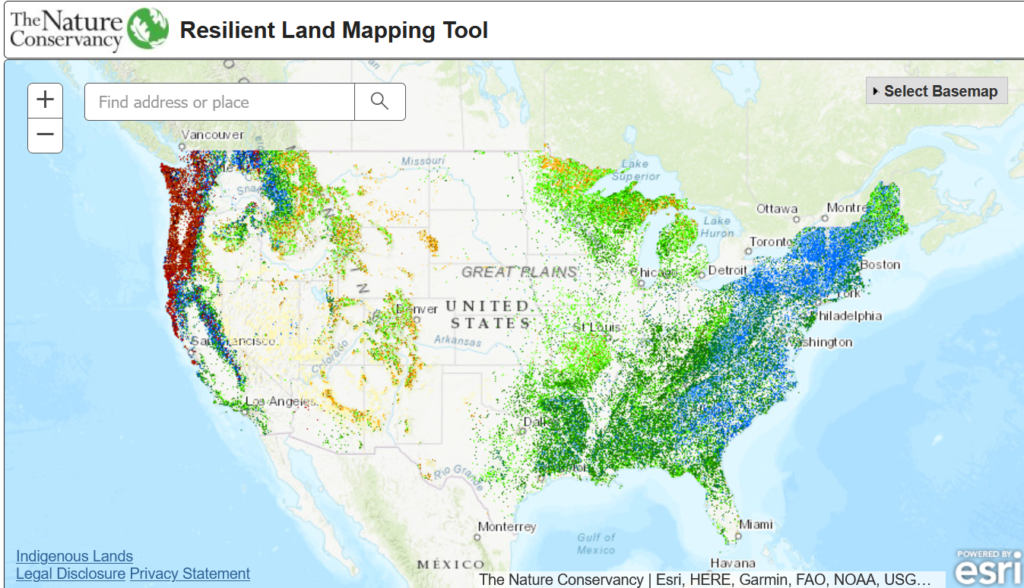

This data-driven approach is not limited to our work in cities. The Reforestation Hub, which we developed in partnership with The Nature Conservancy in January, doesn’t generate scores. But it does use cutting-edge scientific analysis of all U.S. land to identify where more trees could be added, from burn scars on national forests to streamside tree buffers on farms. It identifies a total opportunity of 133 million acres, enough land to plant more than 60 billion trees.

This has huge implications for climate change. That many additional trees would increase annual carbon capture in U.S. forests by more than 40%, equivalent to removing the emissions from 72 million cars.

Like Tree Equity Score, the Reforestation Hub is a free and easy-to-use tool meant to catalyze action. It is searchable county-by-county, enabling everyone to explore how our reforestation opportunities overlap with different land ownerships and conservation purposes, such as wildlife habitat and water protection. It also provides a calculation of the additional carbon capture that would be achieved if a given area were reforested. At American Forests, we use it often to advocate for reforestation legislation and make decisions about where to do our reforestation projects.

I encourage you to jump online and check out these powerful new tools. I hope that you will be inspired by our use of data to measurably challenge America and our own organization to meet this moment.

To learn more about Tree Equity Score, visit treeequityscore.org, and to learn more about the Reforestation Hub, visit reforestationhub.org.

Jad Daley is the President and Chief Executive Officer at American Forests.

This article was originally written for the American Forests website.