It doesn’t take a crystal ball to see: we’re in for another explosive wildfire season across the western U.S. Climate change has been baking our forests tinder dry for years, and with temperatures climbing and summer on our doorstep, we’re practically guaranteed another year of devastation. But that doesn’t mean all hope is lost.

This year, as in recent years, we’re sure to see millions more acres burned compared to fire seasons just a few decades ago. And much of that land will be so scorched that trees won’t regrow if we don’t plant them. One response to this crisis must be to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that are driving climate change and killing our forests. But the future of our western forests will also hinge on this: How quickly we can regrow millions of burned over acres with climate-resilient forests able to thrive in a hotter and drier world?

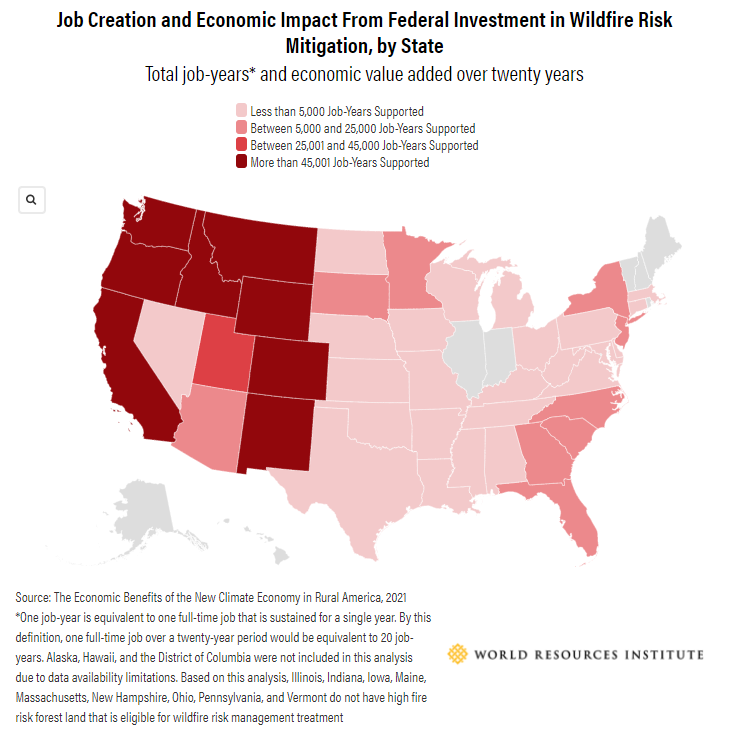

Climate-adapted reforestation will do more than just save forests — it will also help save lives and property, too. That’s because planting climate-resilient forests is a crucial opportunity to get ahead of escalating wildfire threats in our western communities. The need for scaling up forestry actions to increase wildfire resilience, like radically thinning vulnerable forests, could be reduced if we are able to reforest millions of acres of burned areas with the right forest structure and composition to be more wildfire resilient from the start.

To understand the urgency and scale of needed action, we need to appreciate how dramatically climate change is impacting forest health. Climatic shifts have ramped up forest stressors such as drought, pests, disease and catastrophic wildfire. Dried out, sickly forests are just a tinder box waiting for a spark, like parts of the Front Range in Colorado and Sierra Nevada in California that have seen unprecedented forest mortality over the last two decades.

At this moment when our forests are increasingly vulnerable, our expanding human footprint means we are accidentally igniting more fires, creating a verifiable powder keg. This is happening at the same time that climate-fueled increased frequency in dry weather lightning are also more readily sparking fires.

As a result, the extent of western wildfire has doubled in the last few decades, including more expansive and intense “mega-fires”. To give a sense of scale, U.S. wildfire seasons now routinely burn more than 10 million acres per year. In California, roughly one out of every eight acres of forest has burned in the last decade.

It is not just more acres burning, but also how they are burning. Soils can be so scorched from these fires they are made hydrophobic, which means they repel water, and must be remediated to support healthy, native forests again. When mega-fires burn whole landscapes, this can push any seed source from live trees too far away to help support natural regeneration.

By way of example, roughly half of the newly burned areas each year on America’s national forests now require planting in order to recover, a percentage that continues to rise because of the growing extent and severity of today’s wildfires. As a result, the U.S. Forest Service is at least 4 million acres behind on reforesting national forests that need it — roughly 1.2 billion trees. By some estimates, this reforestation backlog on our national forests could be more than 7 million acres, which is an area the size of Maryland.

Wildfire is also happening in places that have historically not burned as often — like our highest mountains. In 2021, wildfire burned clear across the Sierra Nevada mountain range for the first time in recorded history. And then it happened again in the same month. The same phenomenon has occurred in Colorado, where in 2020, wildfires burned across the Continental Divide for the first time. In both cases, this expansion of wildfire impact was made possible by the dramatic drying of high elevation forests that used to be naturally fire-resilient. We must be ready to reforest in forest types and landscape areas that have historically not needed it.

Even our tallest trees are feeling the heat. Experts have long thought that large and old trees of species like the Giant Sequoia were impervious to wildfire due to their thick bark, long distance from ground to branches, and other natural defenses. But climate-fueled wildfires are now putting even these forests at risk, like the Castle Fire in California that killed as many 10,000 Giant Sequoia with trunks of 4-foot diameter or more. That represents a shocking 10 to 15 percent of these trees found worldwide. And while sequoias need fire to reproduce, these fires are reaching such magnitude that the seed bed is wiped out.

With natural processes so profoundly broken by climate change, we need to take a more active role in promoting recovery and fostering climate-resilient forests. For many landscapes across the West, replanting burned areas could save millions of forested acres from potential transition into shrubs and other non-forest cover. To be clear, this does not mean that we must resist these climate-driven shifts in every instance. As I have written before, “pre-storing” forests for climate change will require strategically choosing where to fight back with climate-resilient reforestation, and where we need to allow transition to a different kind of land cover.

Strong science shows millions of burned acres across the West that we can still potentially keep as forest if we make the right moves with rapid reforestation. Losing millions of forested acres unnecessarily would cost America dearly in forgone carbon sequestration, water supply filtration and protection, wood supplies, forest recreation and critical habitat. Of equal concern, un-remediated burned areas are a real hazard to people, triggering mudslides like the ones last year that took out Interstate 70 through Colorado and poured through Flagstaff, Arizona.

So how do we make this happen? There are four interconnected actions we must take to rapidly reforest burned areas with a climate-resilient approach.

- Site Assessment and Planning: The first step is to assess each burned area for its own unique context. We can use science to determine which burned areas are positioned to naturally regenerate, sometimes with a little help, and which ones need tree planting. This prioritization must also overlay other considerations: climate threats; which burned areas are most important for water supply protection or are most at risk of mudslides; and which areas have the greatest value for carbon sequestration, habitat, recreation and wood supplies. Additionally, having post-disturbance plans in place will help speed up reforestation response times. Rapid reforestation is important in order to contain competition from shrubs and invasive species.

- Align Tree Species and Genetics: For areas that we determine need to be planted, we can use cutting-edge scientific tools and traditional ecological knowledge to assess which tree species and genetic strains are best matched to current and future climate conditions. Then we must work with local seed collectors and tree nurseries to collect the right seeds and grow the right seedlings to match this climate-resilient planting approach, and to ramp up seed and seedling supplies dramatically — doubling or more in most locations. We can set these seedlings up for success by using new growing techniques in nurseries that will better prepare seedlings for harsh conditions in the field like drought.

- Climate-Smart Planting: It is not just about selecting the right trees themselves, but also how we plant them. Climate-smart planting must include the right site preparation to address wildfire damage to soils and other site repairs, such as stabilization. We must also match the number and distribution of trees planted on the landscape to our new climate realities, including water availability and fire frequency. This climate-resilient forest structure might look very different from the forest that just burned, such as having fewer trees per acre in chronically drought-stressed landscapes.

- Adaptive Management and Research: No matter how well we craft reforestation for climate resilience, we must be ready to learn as we go. We can do this through intensive research and evaluation of replanted areas and management-scale experimentation. But climate change is playing out quickly. We need to be ready to manage reforested areas to adjust their composition and structure based on these observed results, and to use tools like prescribed fire to keep these growing forests maximally aligned for wildfire resilience. For public lands, this means providing the policy guidance, staffing and funding to adaptively manage these reforested lands for climate-resilience.

There’s no dodging it — this will be a huge challenge. We must stand up this new climate-resilient approach to reforestation while simultaneously working at a totally different pace and scale, something akin to the original Civilian Conservation Corps, which planted 3 billion trees over a decade. (No wonder they were known as “Roosevelt’s Tree Army”!) Our climate and communities, both human and natural, need us to step up to this scale of mobilization today.

The good news is that an unprecedented movement is taking shape to advance climate-resilient reforestation, and we can push it over the top with the right actions and investment right now.

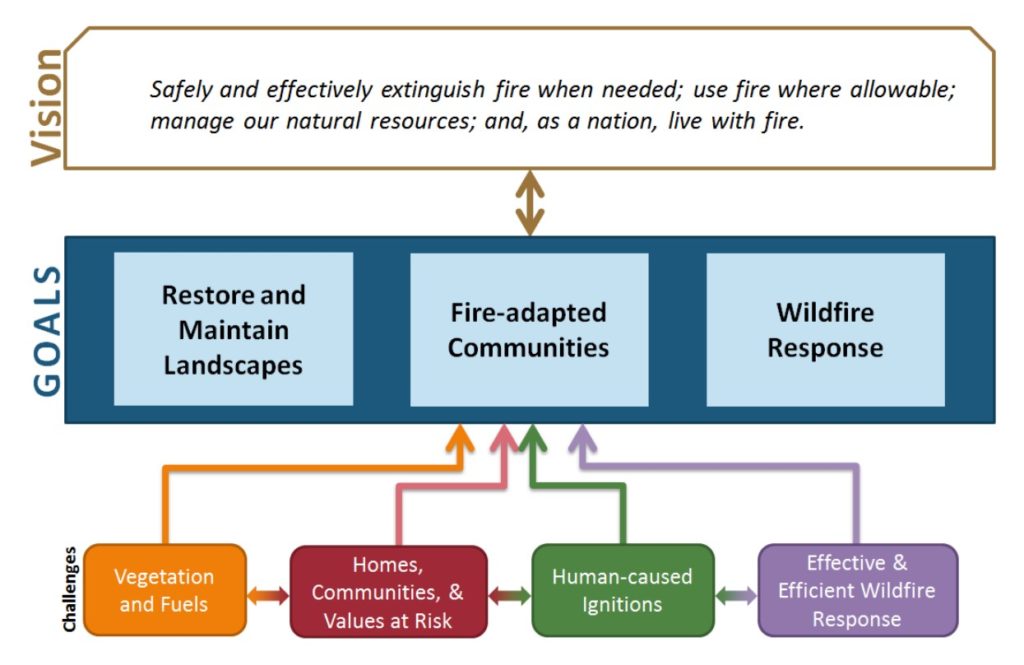

The U.S. Forest Service has painted the target by including climate-resilient reforestation of burn scars as a central pillar in its new 10-Year Wildfire Strategy. The agency recognizes that we can significantly reduce the risk of future wildfires if we use the right approach to how we reforest after the last one. The agency and its partners will need to hold each other accountable to make sure that reforestation does not fall by the wayside as efforts intensify on other aspects of the wildfire strategy, such as hazardous fuels reduction.

We can step up together on the science, too. My organization, American Forests, has seen what is possible through the new Camp Fire Reforestation Plan we co-created with federal and state agencies and financial sponsorship from Salesforce. This plan maps out a climate-resilient approach to reforest one of California’s largest burned areas. Now we are partnering with the State of California to apply this climate-informed planning approach to burned areas statewide. As one way to assure we get the right science in the right hands, the USDA Climate Hubs should step forward boldly to help catalyze this kind of scientific assessment for every state’s burned areas. The Climate Hubs are well-poised to get climate-resilient reforestation guidance out to public and private sector reforestation leaders alike.

The good news is that an unprecedented movement is taking shape to advance climate-resilient reforestation, and we can push it over the top with the right actions and investment right now.

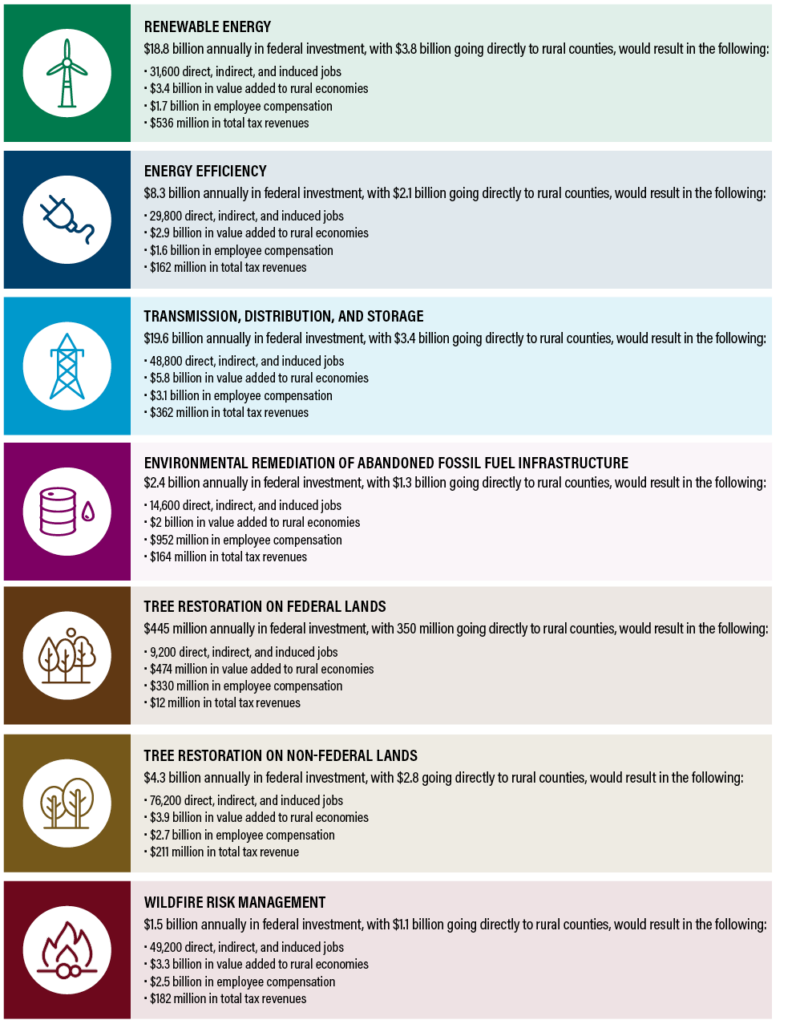

Reforestation at the scale needed will take billions of dollars, and Congress has provided the largest funding allocation in history for post-fire reforestation through the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. This includes the REPLANT Act provision, which will permanently increase U.S. Forest Service funding at least four-fold for replanting on America’s 193 million acres of national forest. It also includes additional funding for reforesting burned areas on Department of Interior lands, expanding seed collection and nursery capacity, and more. But alone, this funding won’t be enough. We need any climate package that might emerge from current discussions between the Biden Administration and Congress to include additional funding for post-fire reforestation, including funding to help states, tribes, local governments and private landowners to do their part alongside federal agencies.

Here’s more great news — the federal government is not in this alone on science, funding or implementation of this reforestation push. An unprecedented coalition of state and local governments, tribal leaders, companies, NGOs and civil society groups organized as the U.S. Chapter of 1t.org has stepped up to match federal efforts. More than 90 partners in the U.S. Chapter have already pledged to plant billions of trees and provide billions of dollars in supporting actions such as nursery capacity, workforce development and carbon finance.

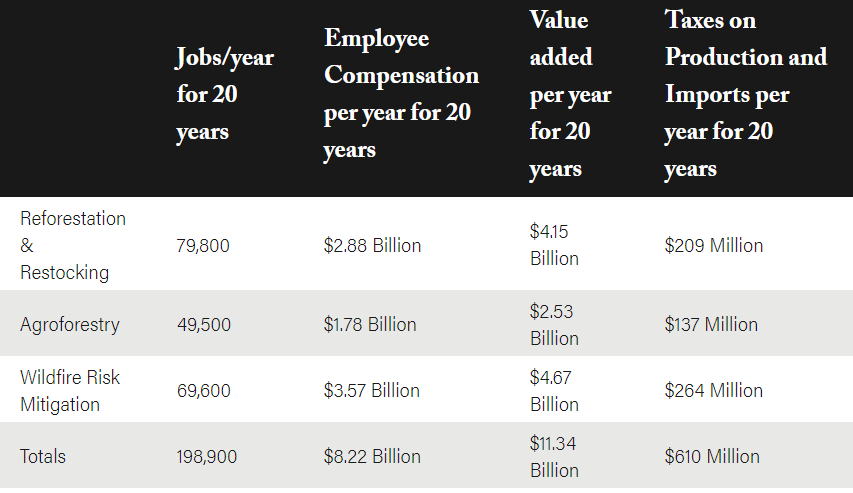

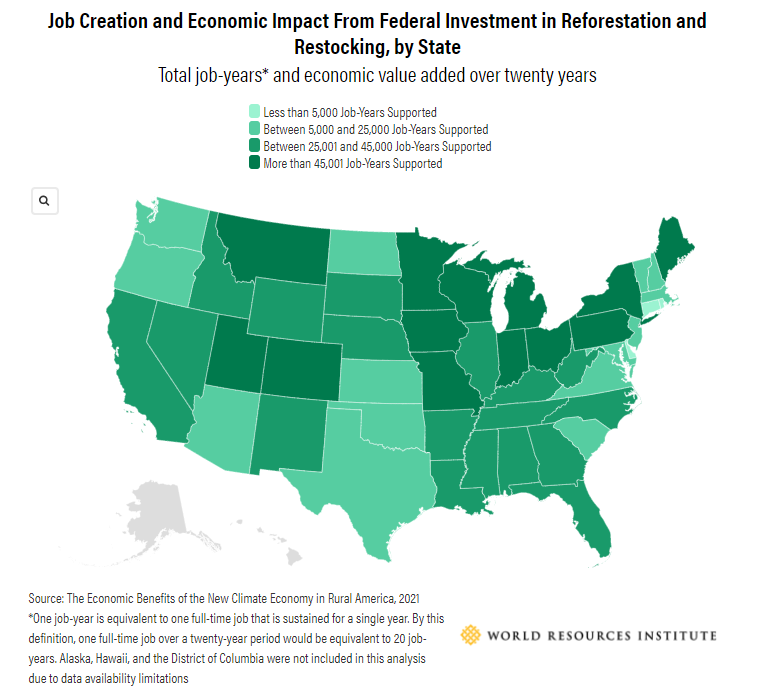

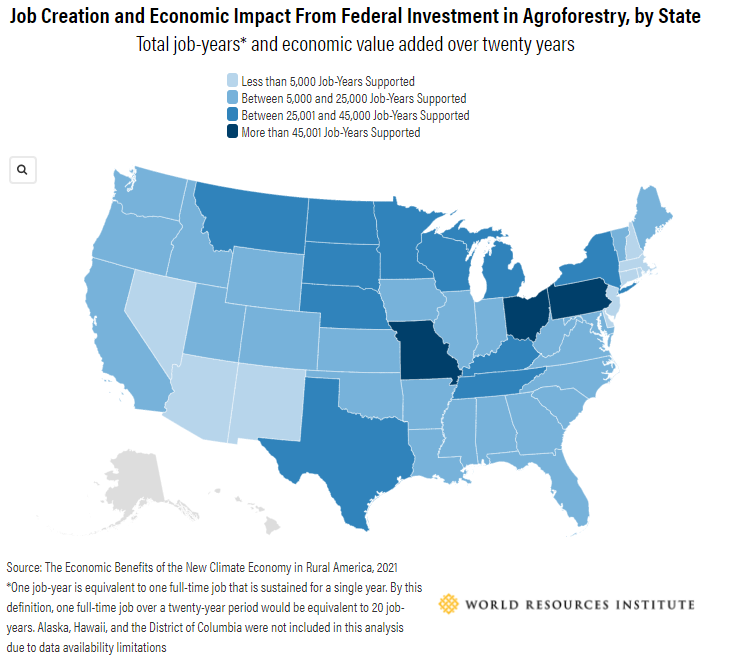

The payoff from reforesting our burned areas will be huge for our economy as well as our environment. Reforestation, from seed collection all the way to conducting and monitoring plantings, has been shown to support as many as 27 direct, indirect and induced jobs per million dollars invested. To achieve our goals, we will need many more employees and businesses working at every point on the reforestation pipeline, now and into the future, employing a wide range of skills. This is an economic development opportunity with huge potential impact in rural communities.

Yes, turning millions of burned acres into climate-resilient forests will be a generational challenge that requires unprecedented investment from the public and private sector alike. With so much at stake, I’m betting America is ready. Taking action that will produce healthier, more resilient forests and local economies? That’s something we all can agree on.

This article was originally posted at americanforests.medium.com.

For more information about efforts to support climate-adapted reforestation, watch USN4C’s video, Building Capacity for Reforestation, and read our accompanying blog article, Reforesting Minnesota: Building Capacity in a Changing Climate.