The seeds of a new agricultural system are sprouting in Minnesota, one that can fight climate change using profitable new crops that keep agricultural lands covered with green, living plants year-round. Crops ranging from perennial Intermediate Wheatgrass (producing Kernza® perennial grain) to new winter annual “cash cover crops” such as winter camelina, pennycress, and winter pea have the potential to amplify carbon storage in plants and soils while also building climate resilience, protecting water quality, improving soil health, and creating new economic opportunities for rural communities. Many of these crops complement and enhance current Midwestern agriculture, whereas others offer new and exciting alternatives. All can bring greater choice to growers, new products to market, and diversification to the agricultural landscape.

The Forever Green Initiative at the University of Minnesota (UMN) is developing and scaling these crops in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, farmer groups, citizen advocates, private businesses, nonprofits, and research organizations. We write as a group of young to mid-career professionals building on groundwork laid over decades. As a group of rising leaders in this effort (among many others!), we want to highlight its recent successes, share its origin story, speak to the value of partnership in advancing climate solutions, and reflect on where we are headed.

Recent wins

In 2022, Forever Green and its partners saw several landmark successes:

- After decades of advocacy, Forever Green was allocated permanent general funding from the Minnesota Legislature to keep developing perennial and winter annual crops.

- Simultaneously, a diverse grassroots coalition succeeded in developing a State pilot grant program to support entrepreneurs to scale value chains for these crops.

- A State pilot program to de-risk grower adoption and increase acreage of these new perennial and winter annual crops is also expanding.

- Nationally, USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service incorporated perennial grains into the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP).

- Through the Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities and the recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act, USDA moved to invest billions in “climate-smart agriculture,” including crops Forever Green is developing, like winter camelina.

- In the Fall of 2022, Forever Green hosted USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service and representatives from over 30 countries to learn about these crops and their potential to address grand global challenges around soil, water, climate, and biodiversity.

These early successes have required decades of careful perennial partnership in science and society for new perennial and winter annual crops to start transitioning from ideas to reality.

Since 2022, Forever Green and its parters have also had some other big advocacy wins:

- The Minnesota Legislature has committed $6 million from the Clean Water Fund to support the Forever Green Initiative (FGI), along with an extra $1.604 million from agriculture committees. This funding ensures that vital roles like breeders, agronomists, and managers can be sustained.

- The MN Legislature also allocated $500k to the Department of Agriculture’s “Developing markets for CLC crops” grant program to support supply chain businesses. This brings the total awarded to $1m since its inception in 2022.

- Productive dialogues with the Risk Management Agency and the Natural Resources Conservation Service have aimed at streamlining the path for farmer adoption of Conservation Leverage and Collaboration (CLC) systems, which currently face disincentives due to federal regulations. As a result, NRCS has approved winter camelina and pennycress for inclusion in EQIP and CSP, two primary conservation cost-share programs (with Kernza already approved in 2022). Efforts with the Risk Management Agency regarding crop insurance coverage are ongoing and at earlier stages.

Kernza in Minnesota: A land-grant university gets behind perennial grains

Nearly 40 years ago, visionaries at The Rodale Institute and The Land Institute had the wild idea that producing grains from perennials—plants that grow for multiple years—could form the basis of more ecologically sound agriculture. Kernza® perennial grain is the first of these to reach farmers’ fields. This perennial’s deep and dense root system draws down carbon and regrows for years without the need for carbon-emitting tillage and the costs of annual replanting. It also reduces runoff and erosion, soaking up excess nutrients that can impair surface and groundwater, harm human health, and act as powerful greenhouse gasses. Recent research shows that Kernza reduces nitrogen loss by over 95% compared to corn.

LEFT: Kernza has roots up to 10-feet long. RIGHT: Kernza grain. Photos by: Alita Films

Concurrent to early perennial grains breeding efforts, University of Minnesota researchers, including Dr. Don Wyse, were leading the basic science that spurred the development of a grower-owned, multi-million dollar perennial ryegrass seed industry in Northwest Minnesota. Together they learned that providing growers with a new profitable crop option was the quickest and best way to scale up the environmental benefits of perennial groundcover. Moreover, developing that new crop option required working together across disciplines and sectors. The University of Minnesota began expanding this model to other perennials and winter annuals in the early 2010s, including Kernza, in partnership with The Land Institute.

UMN Forever Green: A platform for agricultural innovation

Today, the Forever Green Initiative is a uniquely broad innovation platform that supports the research, commercialization, and societal change required to transition toward continuous-living-cover agriculture in the Upper Midwestern US. Housed at the University of Minnesota, Forever Green supports over 15 interdisciplinary crop teams of plant breeders, agronomists, soil and water scientists, food scientists, economists, and commercialization staff. In addition to Kernza, Forever Green scientists are working on:

Beyond the university’s walls, Forever Green’s unique commercialization, adoption, and scaling program supports a wide range of growers, entrepreneurs, and businesses, taking these new crops to market in the form of new food, feed, seed, industrial, and energy products–spanning baking flour to biopolymers to biofuels. A coalition of advocates called the Forever Green Partnership continues the cross-sector work of advocacy, learning together, and building momentum. Forever Green has engaged hundreds of students and early career youth throughout its structure, preparing cadres of young scientists and professionals to continue tackling grand global challenges such as climate change.

Minnesota is now a leading hub of research, development, and innovation in perennial grains. A University of Minnesota research team works closely with The Land Institute and several others to holistically tackle breeding, agronomy, environmental science, food science, and commercialization. UMN Kernza breeders are making headway, increasing grain yield by an average of 10% per breeding cycle. Sustaining this increase would mean achieving yields equivalent to wheat in under a generation–an exceptionally fast and remarkable feat in the world of plant breeding. This work has led to the release of the first commercial Kernza variety, MN-Clearwater. Minnesota also hosts the USDA-supported KernzaCAP project, integrating research, commercialization, policy, and education across multiple states.

INNOVATION Perennial Pantry is a dedicated Kernza processor and food brand, taking Kernza directly from the farmer and turning it into a variety of food products. Photos by: Alita Films.

Outside the laboratory and research plots, Minnesota farmers are growing several thousand acres of Kernza® perennial grain–one-third of all commercial Kernza acres. The state is home to a new grower-owned Kernza cooperative, a startup food company devoted to putting delicious perennial products on your plate, and numerous small and large food businesses developing new products ranging from cereal to naan to beer.

Fertile ground for change: Developing alternatives through partnership

The seeds planted by visionary researchers would never have taken root in Minnesota without supportive state agencies, policymakers, committed advocates, and conservation-minded farmers. Their support grew from a long-standing concern that nutrient loss and erosion from Minnesota’s 20 million acres of agriculture threaten the state’s 10,000 lakes, the Mississippi River Watershed, and the people that rely on them.

In 2004, a coalition of these entities formed a network called Green Lands Blue Waters to collaborate across sectors and states to scale up “continuous living cover” agriculture, which has been a critical partner in advancing perennial grains ever since. In the ensuing years, Minnesota advocates secured resources to develop perennial and winter annual crops from the State’s general fund, the Department of Agriculture, a unique state Clean Water Fund funded by sales tax, and a commission on natural resources funded by the state lottery. These state funds have been used to unlock 5-10 times more funding from federal, philanthropic, and other sources.

As the economic potential of these new crops became apparent, the coalition broadened to include farmers, rural economic development interests, community-based conservation organizations, and food and agriculture companies, large and small. Together, this uncommonly broad coalition has created fertile ground for innovations like Kernza and other new crops to take root.

Carrying the torch: Voices of the next generation

Accelerating the transition

As we work to stave off climate disaster, transforming the world’s agricultural systems into a giant carbon sink is one of the most hopeful avenues for progress. We believe that advancing Forever Green agricultural systems is a key part of that transformation, and we hope this story will inspire farmers, researchers, advocates, companies, citizens, eaters, and policymakers across the U.S. and worldwide. First, to believe in wild ideas with transformational potential, and second to work together to make them a reality. Some ways you can advance this work include:

- Join your local soil health and regenerative agriculture movement, whether it’s as a citizen, consumer, employee, grower, or entrepreneur.

- Learn more about the priorities identified in Farm Bill Law Enterprise’s recent Climate and Conservation Report for the 2023 Farm Bill.

- More specifically, support continued development of perennial and winter annual crops as a climate adaptation and mitigation strategy–in Minnesota, your state, and the country.

- Show grassroots people power by signing on to the Regenerate AmericaTM campaign.

- Feed friends and family the message by enjoying Kernza perennial grain and similar new products at home. You can even now sign up for a monthly Perennial Share!

- Pursue an education or career that will help advance the grand transition toward a ‘forever green’ agricultural landscape.

No one effort will be sufficient to slow climate change. It will take leaders in every state, at the federal level, and in every country. It will happen in laboratories, on the land, on loading docks, lunch tables, and in legislation. It will take all our hands to lift new ways of farming that simultaneously work for growers, create value for companies, reduce emissions, and create a climate-resilient future. Join us!

Prabin Bajgain is the Kernza breeder at the University of Minnesota and a Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Agronomy and Plant Genetics.

Colin Cureton is the Director of Adoption and Scaling for the Forever Green Initiative in the Department of Agronomy and Plant Genetics.

Jess Gutknecht is an Associate Professor in the Department of Soil, Water, and Climate, a Fellow of the UMN Institute on the Environment, and recipient of the Community Engaged Scholar Award at the University of Minnesota in 2022.

Mitch Hunter is the Associate Director of the Forever Green Initiative and an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Agronomy and Plant Genetics.

Margaret Wagner is Manager of the Fertilizer Non-Point Section at the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. She received an MS from the University of Minnesota and was a graduate fellow at The Land Institute in 2007.

Related Resources

Download project fact sheet

(includes pathways for scaling)

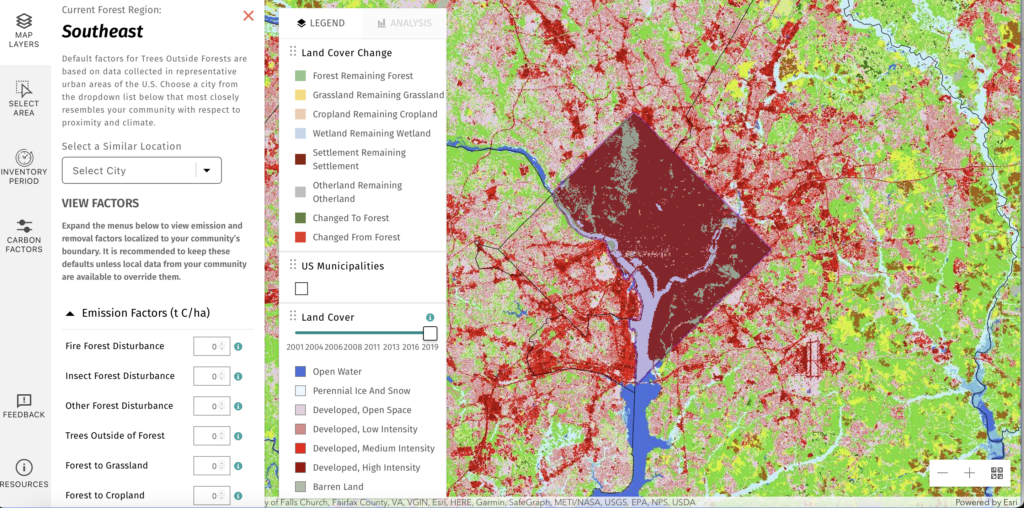

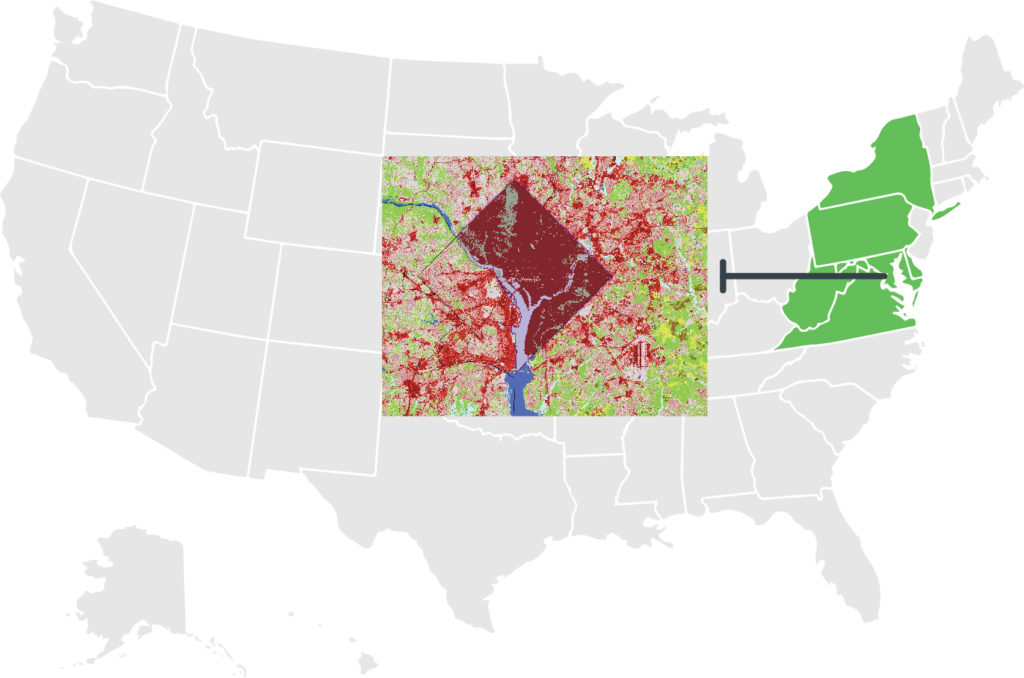

Explore our Decision-Makers Guide to Natural Climate Solutions to better understand the science behind these strategies and get tools to implement them.