Trees can improve water quality, bolster soil health, create wildlife habitat, strengthen local economics, and sequester carbon. There are a myriad of strategies by which trees can be integrated into diverse landscapes as a natural climate solution, including agroforestry (e.g. riparian buffers, windbreaks, silvopasture, alley cropping, food forests), reforesting and/or restocking forests, and urban tree planting. In the United States, reforesting and restocking forests, in particular, hold considerable climate mitigation and economic development potential: reforesting and restocking 185.4 million acres of non-federal lands could remove 156 MtCO2e per year by 2030 and support nearly seventy thousand jobs annually (Leslie-Bole 2021).

Projects that support tree planting by national and corporate actors have had variable success globally, as planting and caring for trees long-term can be an involved and complex social and ecological process that requires critical analysis and thoughtful engagement with numerous stakeholders (Pearce 2022). The need for multifaceted collaboration with diverse stakeholders is particularly true in the U.S. where land suitable for growing trees is often situated within a patchwork of privately and publicly owned land. One pervasive challenge that undermines the potential for ecologically resilient tree planting projects in the U.S. is the nation’s weakened reforestation pipeline–the actors, processes, and materials involved in tree planting, including seeds, nurseries, and planting and post-planting actions.

The main challenges undermining the reforestation pipeline in the U.S. include:

1. Infrastructure (nurseries and seed storage and processing facilities)

In recent decades, the number of nurseries in the U.S., including state and federal nurseries, and seed storage and processing facilities has declined.

2. Demand for trees exceeds supply

The production of trees of various age classes is lagging in the U.S. This imbalance will likely be exacerbated by the demand for trees from growing interest in restoring and reforesting ecosystems across the country.

3. Workforce

Job opportunities in the nursery industry can be physically taxing and are often seasonal, which poses significant challenges for job retention. Furthermore, roles are highly specialized, requiring extensive knowledge of reproductive cycles, growth requirements, phenology, and the plasticity of local flora, as well as the unique skills to collect, germinate, and grow trees. Frequent employee turnover can limit the scale and diversity of nurseries’ production.

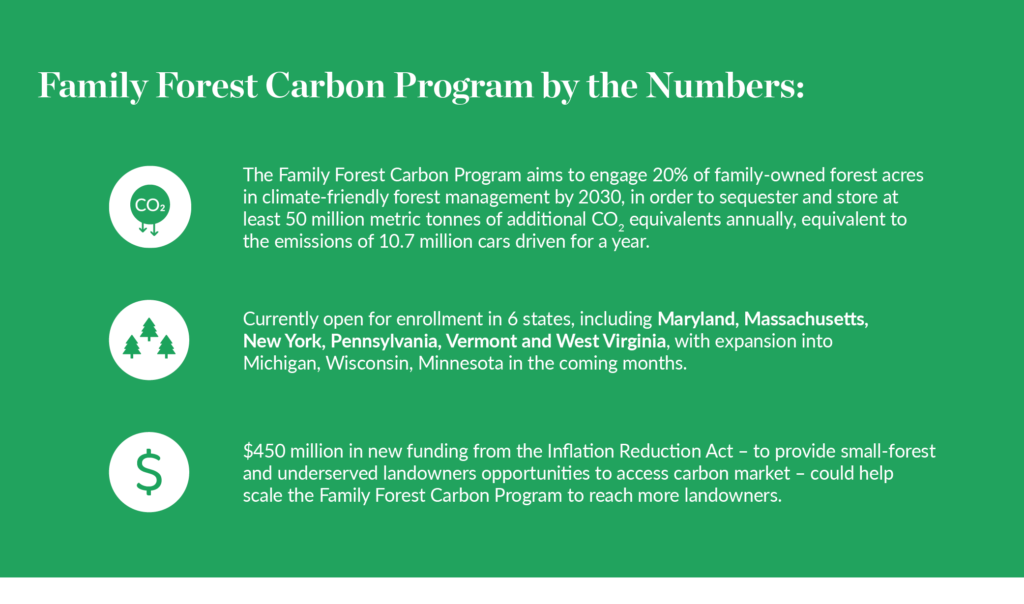

Fortunately, recent, historic, investments in tree planting/reforestation in the U.S. have the potential to address these barriers and galvanize a robust reforestation pipeline: the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) allocates $450 million for climate-smart forestry and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) removes the cap on the Reforestation Trust Fund. These investments could support healthy and resilient forests, as well as enhance community well-being, including by creating jobs, improving water quality, building resilience to climate change, and more. It is vital that these recent–as well as any future–investments in the reforestation pipeline acknowledge that each region in the U.S. is experiencing a unique permutation of the above challenges. Place-based research, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders, is vital to understanding the unique context and needs of regions across the U.S. to develop and implement sustainable and equitable tree planting/reforestation efforts.

To elucidate opportunities to bolster the reforestation pipeline and meet the growing demand for trees by tree planting/reforestation projects, we conducted semi-structured interviews with seven nursery managers in the Northeastern U.S. These interviews yielded key insights on the state of the reforestation pipeline in the region and nursery managers shared their unique perspectives on opportunities to improve this vital supply chain.

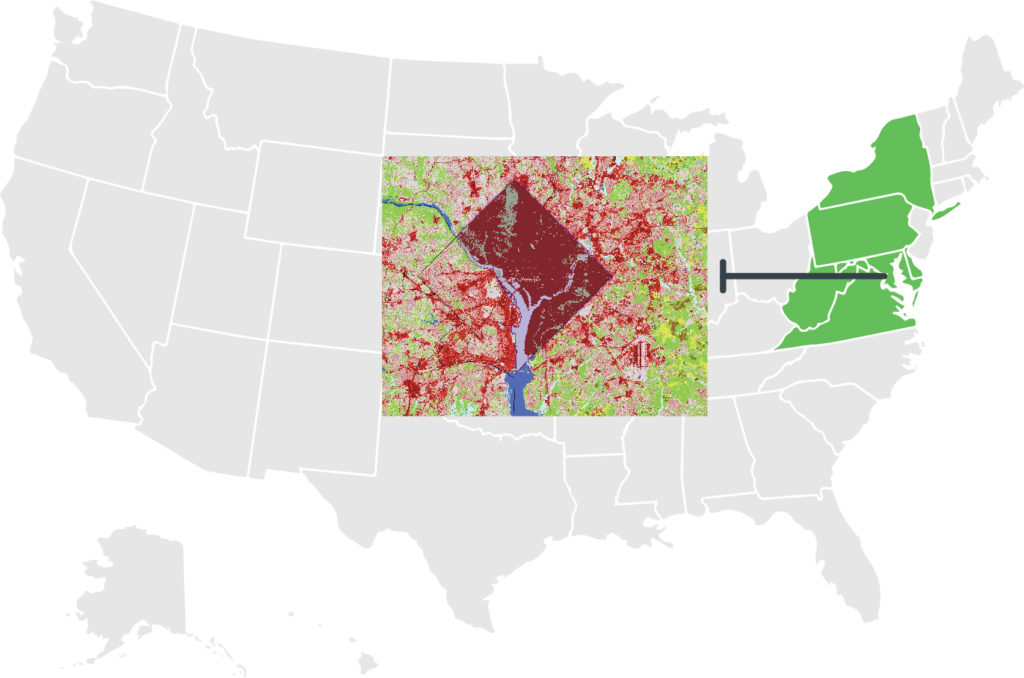

The Northeast differs from other regions of the country as both forests and land suitable for NCS (e.g., floodplains, marginal croplands, pasture, abandoned lots) is dominated by private land ownership. Furthermore, natural regeneration is often the most economically viable and ecologically suitable model for reforestation in the region. In fact, the Northeast has a rich history of land use change where much of currently forested areas were once cleared and have since undergone regeneration and succession (Foster, 1992). Still, trees in and outside of forests in the Northeast are facing many challenges. For example, the implications of climate change are amplifying forest health risks (species range shifts, pests, pathogens, drought, temperature shifts) and the persistence of market pressures incentivizing forest conversion (e.g., housing development and renewable energy installations) are commonplace. As such, reforesting and restoring forests in the Northeast amidst these challenges will likely require more input and active management than the forests that returned to the region in the early twentieth century.

Despite the challenges facing the reforestation pipeline, there is growing interest in planting trees for climate resilience, carbon sequestration, improving air quality, diversifying markets, and more. Among other strategies, current projects are focused on urban tree planting, riparian restoration, and agroforestry. According to recent models, large-scale reforestation has the greatest climate mitigation potential (35 percent) in the Northeastern U.S. (Fargione et al., 2018). Given that recent studies have illustrated that many landowners in tropical and subtropical forests are more interested in the utility trees offer rather than their climate mitigation potential, there may be a greater demand in the Northeast for trees that can enrich landscapes by offering multiple functions (e.g., trees for food, timber, and aesthetics) (Martin et al., 2022). As such, efforts to accelerate the pace and scale of tree planting/reforestation in the region will need to be advanced in close collaboration with landholders and will require a rich understanding of the challenges facing the region’s forests.

The goal of the semi-structured interviews we conducted with nursery managers in the Northeastern U.S. was to better understand the breadth of nursery operations, nursery managers’ interests in expanding production to meet anticipated higher production, and growers’ recommendations for pivotal investment opportunities to bolster production while also providing ecological, economic, and social benefits. The individuals we spoke with manage operations that vary in size, age, location, infrastructure, objective(s), and end user(s). Interviewees included the managers of private nurseries, a state-run nursery, and a non-profit conservation nursery. The production of each nursery ranges from small shrubs, containers, and bare root. Furthermore, the size of each operation ranges from one acre and three full-time employees to 150 acres and 75 full-time employees. Lastly, the nursery managers we spoke with sell to diverse end users, including farmers interested in establishing agroforestry systems, homeowners, landscaping operations, and large-scale research, conservation, and restoration projects.

Key takeaways from interviews with nursery managers in the Northeastern U.S.:

1. Although nursery managers report a notable increase in demand for their products in recent years, many private nurseries noted that this increased demand has not come from tree planting initiatives. Furthermore, nursery managers were not convinced that large-scale projects would source from local nurseries, most of which are smaller and cannot offer competitive prices as compared to larger operations based in the Southeastern and Western U.S. The skepticism of private nurseries stood in contrast with nurseries with an explicit conservation or agroforestry oriented mission, who had started their production and/or were scaling up in anticipation of increased demand for trees.

2. Most nursery managers we spoke with were more interested in increasing on-site efficiencies (e.g., maximizing the number of trees produced with the least amount of external inputs) than expanding operations due to a limited land base, workforce constraints, and personal capacity. Some nursery managers were interested in expanding production through partnerships with smaller nurseries or with new growers of woody plants.

3. Nursery managers emphasized the importance of genetics, producing locally adapted trees that can survive and thrive in changing climatic conditions, and growing productive species. This sentiment is often echoed by those with experience implementing and monitoring tree planting projects.

As evidenced by these three key takeaways, developing a resilient reforestation pipeline in the U.S. can be achieved by supporting and learning from locally-focused operations and building trusted, long-term relationships with growers in distinct regions. As more detailed funding allocations for tree planting/reforestation and forest resilience are made through IRA and IIJA, as well as in the 2023 Farm Bill, the perspectives of nursery managers and other stakeholders must be considered to grow and fortify the reforestation pipeline that can meet the unique needs of regions across the country.

Initiatives that seek to improve and increase the volume of seed stock for restoration should prioritize support for existing operations. Many private nurseries have persisted and adapted to changing markets amidst the closure of state-run nurseries. These nurseries already possess the infrastructure and skills necessary to adapt to new markets driven by tree planting/reforestation initiatives. However, uncertainty regarding local actors’ commitment to NCS and the consistency of new markets in the coming years pose significant risks for operations that are considering scaling-up production. To better coordinate production to meet anticipated increases in demand, nursery managers will require information from their end users on the species, varieties, and quantity of trees needed, as well as the projects’ timeline. Additionally, many nurseries will need to modify their existing structure to diversify offerings, such as producing younger, bare-root, trees, which are typically bought for restoration projects (versus the larger container or ball and burlap tree that nurseries typically sell at a high price point to homeowners or landscapers). Nursery managers should be involved early, as well as throughout, tree planting/reforestation initiatives’ planning processes. This sustained engagement will not only enable nursery managers to better coordinate their production with projects’ demands, but also offer opportunities for growers to provide invaluable insights on projects’ scope and implementation. Nursery managers already often provide planning guides and offer consultations, drawing on years of regionally relevant experience. This expertise will be invaluable to the long-term success of tree planting/reforestation projects.

One strategy that could support existing operations is the establishment of local prioritization into NCS criteria. This approach would require tree planting/reforestation initiatives to source trees locally, which may help authenticate the promise of new markets for nursery managers, thus catalyzing greater investment in local supply chains. In the absence of such mechanisms, large-scale tree planting/reforestation initiatives may source stock from large growers based in the Southeastern or Western U.S. that are able to offer lower prices due to an extended growing season and the availability of relatively inexpensive land. Similar strategies that prioritize the hiring of local labor and sub-contractors for stewardship contracts on federal lands have been employed (e.g., Consistent Program of Stewardship work in El Dorado National Forest) to maximize local economic co-benefits. In addition, intentionally selecting locally adapted species for tree planting/reforestation projects can help bolster the capacity of populations to adapt to anticipated phenological changes and consequent range shifts predicted in climate change, and thus enhance the long-term success of tree planting/reforestation projects.

Strategies that prioritize local investment in concert with increased demand will continue to attract new and motivated growers to the industry. Several nursery managers we spoke with expressed interest in aggregating trees from other growers when they reached production limits to meet consistent inquiries for nursery stock. Therefore, in addition to supporting existing operations, clear pathways for new and interested growers to access quality land, infrastructure, markets, and technical support will increase the resilience of a regionally-specific reforestation pipeline. Strengthening the capacity of the reforestation pipeline should thus involve the creation of opportunities for diverse producers that can absorb demand from multiple entities and efforts to increase NCS. New programs, including components of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), that facilitate access to land and markets for underserved producers, will be particularly pivotal to ensure that newer and historically underserved growers can participate in the growing market for trees. Such investments must also include access to resources that can help producers strengthen their operations, including in-person workshops, site visits from extension agents or other professionals, and online resources. New and existing growers could collaborate through job trainings, cooperative (co-op) marketing models that aggregate available nursery stock on centralized platforms, and/or by sharing storage facilities (e.g., cold rooms) that can hold trees until they are needed.

Realizing the climate mitigation potential of tree planting/reforestation projects will depend, in part, on the strength of the reforestation pipeline. Although our findings are not conclusive about the attitudes of all nursery managers and growers across the Northeastern U.S., they do showcase the indispensable role of nurseries to the successful implementation of NCS. To fortify the reforestation pipeline, the federal government, alongside key partners such as universities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), must integrate the perspectives and recommendations of key stakeholders, including nursery managers. Ensuring that future policy decisions are informed by landowner and practitioner perspectives will be especially important in national and international policy discussions, including the 2023 Farm Bill. In the absence of place-based research and the inclusion of local communities’ expertise, the potential contribution of NCS to societal well-being and climate goals will not be realized.

Many experts in the nursery industry that we spoke with have long been interested in addressing the pervasive challenges facing the reforestation pipeline, including increasing genetic stock, tracking and communicating technical knowledge, and expanding production through collaborating with other growers to meet the demand for trees. The many skilled individuals working at nurseries and across the reforestation pipeline know what it takes for the industry to grow and the diverse actors (e.g., national and state governments, NGOs, and corporations) seeking to galvanize a more robust reforestation pipeline and accelerate the pace and scale of NCS implementation should take note.

To learn more about the challenges in the reforestation pipeline, read Reforesting Minnesota: Building Capacity in a Changing Climate, Seeing the Forest for the Seedlings: Challenges and Opportunities in the Effort to Reforest America, and Gisel Garza: Seed Hunter.